It was spring of 1972 when Anne Fulton stumbled upon a poster that read It’s Time for Gay Liberation. That rallying cry appealed to the budding lesbian activist—Fulton was 20 then, maybe 21—and she went to the meeting the poster advertised. This gathering would turn out to be vital, for both Fulton and, more than 40 years later, what we now consider Halifax’s LGBTQIA and Two-Spirited community.

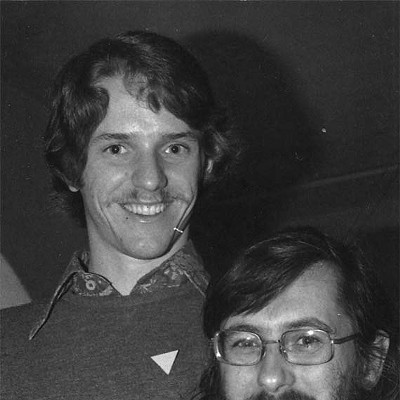

Details about the meeting still exist, in the form of a handwritten note kept in Nova Scotia’s unofficial queer archives, a little house overlooking the water just outside of Sheet Harbour that’s owned by Robin Metcalfe. The meeting was organized by Dartmouth-raised Saint Mary’s University alumnus Frank Abbott, home from Toronto where he was a member of the Community Homophile Association of Toronto. About 14 people attended, most if not all of them male except for Fulton. There was David Gray, owner of Halifax’s first official gay bar, Thee Klub, and an international student from China named David Yip.

After the meeting, Fulton took a warm and breezy walk down Rainnie Drive with Abbott. Before they parted, he put his arm around her. “I had the very distinct feeling of having been passed the torch of gay liberation,” she wrote in 1981. “And I believe I’ve carried the torch for many years since then. (Burnt myself with it a few times too.)”

Fulton, a founding member of Nova Scotia’s inaugural gay and lesbian organization, the Gay Alliance for Equality, passed away in November of 2015. Friends and fellow activists couldn’t believe Fulton was actually gone. Not only was she a mere 64 years old, but Fulton was one of the few who could speak to those early days of the GAE.

Now her papers and writings carry on that historical role, enabled by the queer archives. Metcalfe is the archivist, keeper of what is surely the largest collection of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer ephemera and historical documents in the province, including a box of Fulton’s personal archives—that collection will end up in the Public Archives of Nova Scotia.

Metcalfe and I are friends. For me, this was the first intergenerational friendship I, a “young” 31-year-old queer woman, had with a queer elder. He is 30 years my senior, born in 1954, the same year as my mother. We first met in 2012 when he was giving a talk on the history of Pink Triangle Day, our national queer holiday. Metcalfe drafted the resolution for the holiday, passed at the 1979 general meeting of the Canadian Lesbian & Gay Rights Coalition to mark the Valentine’s Day acquittal of Pink Triangle Press on charges of immorality and indecency. We’ve been meeting over half-decaf coffee for the last three years, talking for hours about queer life, politics and history.

He’s the director/curator of the Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery, but Metcalfe has an archivist’s soul. His Halifax apartment is lined with hundreds of neatly shelved books, with everything—absolutely everything—in its place. Even during our meandering casual coffee dates, Metcalfe will jump up to jot down a name, an event, an idea in his notebook. His brain is a lot like his archives on the Eastern Shore: Everything meticulously labelled and filed, so he can pull out a memory, a name, a place, a date, when called upon. He’s a remarkable asset for a community whose history is not bound by blood, and so often has been recorded in the margins—if recorded at all.

Most LGBTQIA people are not born into queer or trans families and don’t grow up hearing stories about the Compton Cafeteria Riots (San Francisco’s precursor to Stonewall); Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera and Miss Major Griffin Gracey; or the 1981 Toronto bathhouse raids around the dinner table. It’s often up to us to locate our community—our elders—and uncover our LGBTQIA history. And these conversions, these relationships—the first between young activists and those 30, 40 and even 50 years our seniors—are in themselves historic.

The queer or, to use the vernacular of the day, “gay and lesbian” elders who are now in their 60s and 70s are Halifax’s first generation of LGBTQIA activists. When being queer meant risking the loss of your job, your family, your life, they were still here in Halifax. They were organizing, dancing and blazing a path forward for the generations of us still fighting for our rights today.

In the early 1970s, Canadian gays and lesbians were barely legal. Homosexuality was decriminalized by Trudeau Sr.’s Liberals only in 1969. Gays and lesbians living in Nova Scotia had no protections under the Human Rights Act.

That same year, in New York City, a group of queers, street kids, trans women of colour, drag queens and sex workers fought back when their haven, the Stonewall Inn, was again raided by police. The 1969 Stonewall uprising, one of the riots that birthed the queer and trans liberation movement and modern-day Prides, didn’t translate to the Maritimes provinces, says GAE alum James MacSwain.

“New York was at least 10 to 15 years ahead of anything that was going to happen in the Maritimes,” he says. MacSwain, who was studying English Literature at Mount Allison University in 1969, didn’t read about Stonewall until he was living in Halifax in the mid-’70s.

That doesn’t mean Halifax was strictly hetero, of course. It’s a port city, with a large naval presence. We’ve been here, and we’ve been queer, but haven’t always been out and organized. When Metcalfe and his cohorts were my age in 1970s Halifax, the only activist elders were those who had founded the GAE just a few years earlier. They simply couldn’t sit down over coffee with people 30 years their senior and shoot the shit about gay and lesbian activism in 1940s Halifax.

“Our activism was a barrier between us and older gays,” Metcalfe says.

In her early 30s, Brister was the oldest lesbian she knew. The mentors she did find were a couple her age who had been out a decade longer. Several years later, at the 1978 Annual Conference for Lesbians and Gay Men in Halifax, the 37-year-old Brister would facilitate a workshop on “older lesbians.”

Desperate for community when she first came out, Brister called the GAE phone helpline and wound up, like so many others, at Thee Klub. Nicknamed “David’s,” Thee Klub opened in 1971 in the Green Lantern Building at 1585 Barrington Street.

Brister remembers pacing back and forth in front of the building’s street-level door for what “felt like a hundred times,” until she stole the confidence to duck in while no one was watching. “In those days,” says Brister, “when you met people you never gave your real name because we could lose our jobs or we could lose our children.”

Thee Klub didn’t have a license, and was only open two nights a week (save long weekends). It was small and, in the great tradition of gay bars, dimly lit. A “late-night sneak-about,” says Chris Shepherd—another Dartmouth boy—who first went to David’s in 1974.

“I did what many people did,” says Shepherd. “Walked up and down the street until you saw a break in the traffic and no one on the sidewalk, and then you dashed in.”

That meant waiting until the crowd from the nearby theatre dispersed, which made for some late nights at Thee Klub. “We used to joke, that you could always tell gay people in Halifax because they were the ones with the bags under their eyes,” says Brister.

But it was “liberating,” says former regular and GAE member Mike Sangster. A space to be out, to dance, to neck, to agonize, to organize and, in MacSwain’s words, to “laugh about the absurdity of living in a straight world.”

In the early half of the decade, the places where gay men met were primarily outside and centred around cruising for sex. Popular spots included the Citadel, the Triangle (bordered by Queen Street, Dresden Row and Artillery Place), the Public Gardens, the Common, Camp Hill Cemetery and The Meat Rack (a low brick wall on Spring Garden and South Park now home to a Rogers).“We used to joke that you could always tell gay people in Halifax because they were the ones with the bags under their eyes.” —Nancy Brister, 2016

tweet this

Gays and lesbians frequented bars and restaurants such as the Heidelberg (a German restaurant and lounge on Dresden Row), The Jury Room (where the Carleton is now), The Lord Nelson’s Ladies Beverage Room (women weren’t allowed in taverns until the 1970s) and the Garden View Restaurant (affectionately known as the Gag and Spew). But even those regular haunts didn’t tolerate overt homosexual behaviour.

“For hip people it was cool to know a gay person,” remembers Shepherd. But local businesses weren’t as welcoming. “If you even looked gay you were unwelcome in their establishment.”

Gradually, the community fought to change those discriminatory attitudes. On April 23, 1977, 20 gay men—or men who were assumed to be gay, at least—were asked to leave The Jury Room. Shepherd was one of them. He was arrested for drunk and disorderly behaviour after half a drink. The men were called “queens” and told that “people of your kind” wouldn’t be served.

The next night, Fulton, MacSwain, Metcalfe and fellow GAE member Deborah Trask went to The Jury Room to test the policy and were denied entry. A week later, a crowd of 30 protesters picketed the establishment’s discriminatory rules.

It was one of many battles the the Gay Alliance for Equality would rally the community around over the later half of the decade. The ‘70s galvanized the community, crackling with a “real gathering of confidence and energy,” says MacSwain.

“It was wonderful to get to know gay men in the context of: These are gay men and they’re saying they’re gay men and that’s that,” he says. “Meeting lesbians for the first time and having conversation about feminism and separatism. Debates around power and patriarchy. That was all really exciting to me.”

The fledgling Gay Alliance for Equality was founded in 1972. The founders, nearly equally women and men, were tradespeople, students, teachers, laundry workers, businessmen, accounting clerks and a railway porter. They met in members’ homes as well as the Unitarian Church on Inglis Street.

But by 1974, the GAE had ceased operations. Robin Metcalfe, who was living in Edmonton and working on the railroad, had been trying to contact the gay group in his home province of Nova Scotia to no avail. During a stopover in Montreal, he came across an ad for a GAE meeting at the Universalist United Church. The minister put Metcalfe in touch with some of the GAE’s founding members, and Metcalfe set about reinvigourating the group.

In October of 1975, the GAE held its first general meeting in nearly a year. The Alliance worked itself back up to 68 members, and re-launched the gay telephone help line (the “Gayline”), securing a memorable phone number: 429-6969.

As the name suggests, the Gay Alliance for Equality was founded to serve members of the “gay community” (both men and women). There was no B and no T, let alone any Qs, Is or As.

Lynn Murphy, who got involved in GAE in 1977, identified then and now as bisexual. “Of course within GAE they knew that there was no such thing as bisexual,” she quips.

The only mention of trans identity in the GAE file inside Nova Scotia’s Public Archives is part of the meeting minutes from February of 1976. “GAE speakers are frequently asked for information on transexuality and transvetitism which they are unable to provide,” it reads. “It was agreed that organizations for transsexual and transvestites would be contacted.”

It is difficult to determine how many people would have identified as transgender if there was the language, resources and support. The word “transgender” was only coined as a psychiatric term in 1965, and was first used by trans activist and Transvestia publisher Virginia Prince in 1969.

The Alliance was also—perhaps unsurprisingly in Nova Scotia—largely white. According to Chris Shepherd, who was treasurer in 1980, there were only a “handful” of black GAE members. One of the founding members was a Mi’kmaw woman, but she does not reappear in any of the GAE records.

Walter Borden—a self-described African- Mi’kmaw, gay Canadian—spent the 1970s working for Black United Front and on stage at Neptune Theatre. “We just didn’t have time for [the GAE] because we’re dealing with something else here,” says Borden. “Unless something was really defined and profound, you just didn’t have time to deal with it.”

Coming of age during the black liberation movement of the 1960s, Borden spent his time working with the Nova Scotia Project—the civil rights group founded by his cousin, Burnley “Rocky” Jones, along with Joan Jones and Dave Tarlow in 1965. “Within the Project there were those of us who were gay,” says Borden. “It was never an issue. Ever.”

Women were also underrepresented within GAE—which didn’t change its name to include “lesbian” until 1988. Given that women had only recently started earning a minimum wage equal to that of a man’s, many lesbians at the time were on a limited income, and many had children to look after.

In 1976, Anne Fulton wrote in the GAE’s short-lived newspaper, The Voice, that she was the only woman active within the alliance. That year Fulton attended a lesbian conference in Kingston, Ontario that focused on “dyke separatism.” As she put it: “We’d all grown tired of working behind the shadow of the men, of fighting for their aims and of not having the guts and self confidence to fight for, let alone recognize, what we wanted.”

Post-conference, Fulton founded APPLE—the Atlantic Provinces Political Lesbians for Equality. Perusing the public archives, APPLE’s name and logo is attached to a handful of items: A benefit in 1976; a women’s coffee house in 1978; the 1977 Atlantic conference and 1978 national conference held in Halifax, as well as the single-issue national Lesbian Canada Lesbienne newsletter the group published in 1977.

But here is the challenge of documenting history 40 years on: People remember the past differently, nostalgia sets in and it’s difficult to tell if well-documented plans translated into reality. “APPLE never really existed,” says Trask. “It was a nice idea—a group that never really got going.”

Trask’s decision to work alongside men in the GAE drew the ire of some lesbians, who showed up at her door one day and “read me the riot act,” she says. “All these things I had done that were in contravention of what a real lesbian should be.” Not only for being active within GAE, but also for living with a man—her younger brother Tony, himself gay. “He’s my un-employable baby brother!” Trask exclaimed.

Other lesbian groups were less official. Not long after her first foray into Thee Klub, Nancy Brister formed a “consciousness raising group” with a handful of city lesbians. Together, they carpooled to the same Ontario conferences in 1976 as Fulton attended. That was where she first found out about Maggie’s Farm—a women’s collective located just outside Tatamagouche, founded by two back-to-the-landers from Berkeley, California. It was a spin-off of lesbian separatist groups like the Radicalesbians in New York and the Van Dykes (literally dykes who travelled North America in a van), but Maggie’s wasn’t strictly separatist, as the women had two male children. Post-Kingston, Brister and her friends made a pilgrimage up to the farm.“We’d all grown tired of working behind the shadow of the men, of fighting for their aims and of not having the guts and self-confidence to fight for, let alone recognize, what we wanted.” —Anne Fulton, in GAE’s The Voice newspaper, 1976

tweet this

“When we first drove into Tatamagouche we said, ‘Oh my god! It’s a community of lesbians!’ But they weren’t. They were farm women.”

Eventually the lesbian landscape of Halifax changed as more and more women started coming out—many of them in university. Brister says that new wave of academic, politically motivated lesbians changed the tightly knit lesbian community that could fit at a single table at Thee Klub. “We sort of divided into our own groups,” she says. Up until then, “we were being held together by necessity. We were it.”

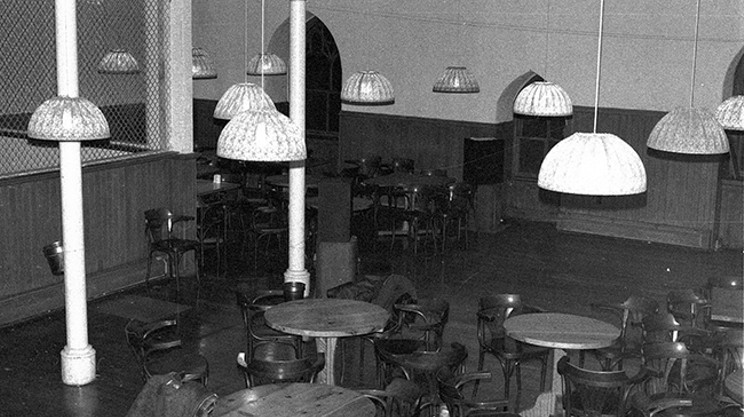

The fervour of the mid-to-late ’70s was due in no small part to the birth of Halifax’s first community-run gay bar, The Turret, on the third floor of the old Khyber building.

In 1976, Robin Metcalfe and John Lewis were barred from the Heidelberg for dancing with a member of the same sex. When the owner refused to discuss the matter with representatives of the GAE, they set up a meeting with the Youth Employment Society. The society was leasing the former Sanpaka restaurant space on the third floor of 1588 Barrington Street and the alliance wanted the space for a gay discotheque.

The night was an “immediate success,” according to the GAE’s minutes, “drawing large crowds and creating a friendly, loose atmosphere.”

It was “a safe space,” says MacSwain. “People can come there and they can dance to their hearts’ content; they can cruise to their hearts’ content; they can love whoever they want to their hearts’ content.”

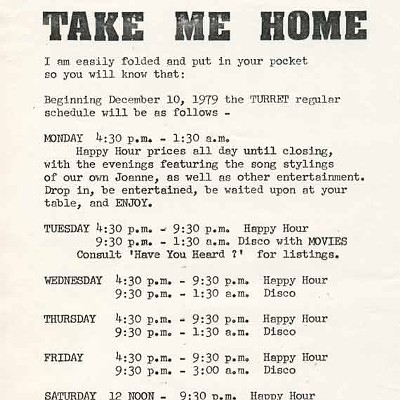

The GAE disco became a bi-weekly event for the next several months, before Trask, Robert Stout and David Seale signed the lease for the Turret for a total of $12,000. On the weekends Chris Shepherd worked as DJ, spinning everything from disco to bluegrass. (According to official GAE minutes, Anne Fulton wanted more waltzes.) Everyone had a lot of fun and a lot of sex, says former Turret staffer Reg Giles.

It was more than just a disco. There was also a folk night, and a women’s night. Faith Nowlan and Dale Cavanagh provided entertainment on Wednesday nights, while Sparrow (the gay and lesbian Christian group run by “Father Mike” MacDonald) used the space on Sundays. It was a drop-in centre and “non-profit gay community centre.”

Membership cards were five dollars, and featured the Turret’s spire-topped tower as illustrated by NSCAD alumnus and visual artist Rand Gaynor. It became the major source of revenue for the GAE, and helped finance the group’s political activities. The bar also provided employment for “unemployable” gay men and some women, according to Trask. Above all else, it was theirs.

“You knew that the moment you stepped into the doors you were stepping into your world,” says Borden. “You could just be. You could just be.”

“For a time, we had in Halifax what no other place in Canada had,” says Trask. “We had a place for the gay and lesbian community that was run by the community.”

Halifax lesbians had preferred house parties to the club, according to Brister, but when the Turret opened in 1976 women claimed their corner of the room’s L shaped space—“dyke corner” as it came to be known. “Where else would you meet a whole bunch of lesbians that you didn’t know?” says Murphy.

But cohabitation wasn’t always easy. During the summer of 1977, Gaynor was commissioned to paint two murals, one depicting gay male sexuality and one lesbian sexuality. The latter, now referred to as “tits and lipstick,” featured two thin torsos with perky breasts and bolts of electricity shooting between the red lipstick-encircled nipples.

Lesbian activists spray painted “sexist” over the busts, and “This is a crime against women.”

In a statement, read at the next general meeting, the women called the mural “an extension of the Playboy image of women as ‘tits and ass,’” one that “portrays women’s bodies in a fantasy form unrelated to female physiology.” A motion was subsequently brought forth to bar the spray-painting lesbians from the Turret indefinitely, but that idea was voted down. The mural was eventually painted over.

A 1978 membership survey gives a glimpse into the scene inside the Turret. Filled out by 95 people—or 25 percent of the Turret’s patrons—the survey asked everything from how much alcohol patrons drank per night to favourite music played (disco was the overwhelming favourite for male members).

The most contentious question asked if there was a “certain crowd or individual type which cause a person to feel uncomfortable” at the Turret. Over 45 percent of respondents replied yes, with many listing the “fighting women,” “dykes,” “truck drivers” and women who came “dressed in men’s clothing...or dirty work-type clothing.”

“The men had just as many fights as the women as far as I’m concerned,” says Giles, who points out that the first person to smack him at the Turret was a man. “It was a little bit harder to control some of the women because they were strong.”

It’s important to remember, says Metcalfe, that it “was an aspect of tough, lesbian working-class culture. They were tough because they had to be tough.”

After the brawlers, drunks, “catty” effeminate men, “pansies,” snobs, security, straights and bisexual men, “stereotypes left over from the ’50s and ’60s” made the list of most-disliked Turret patrons.

These grievances expose not only an element of internalized homophobia (still prevalent today in LGBTQIA circles), but also clear divisions based on class. Whether a lesbian adhered to butch/femme gender roles had more to do with income and less to do with what era they were living in, says Trask.

Despite the minor internal conflicts, the Turret still offered a proud, community-run safe space for gays and lesbians alike. It was a shelter from a city, a country that dismissed and despised them. The need for those kind of queer safe spaces has never entirely gone away.

Two days after the horrific Pulse nightclub shootings in Orlando, Florida, Lynn Murphy sends an email. The importance of “the club” (both a nickname and a code name for the Turret), she writes, went past simply being a place to dance and drink or a source of revenue for the GAE.

“The Turret club (and later Rumours) was a safe space for LGBT people to meet,” Murphy writes. “We built and enhanced our social networks. In our own space we discussed internal issues—politics of drag, LGBT parenting, violence within LGBT relationships. We created our own artistic expressions. We began to see ourselves as a people with common goals, not just as ‘queer’ individuals.”

“Things were tough for gays in the Halifax area,” founding GAE member Dianne Warren wrote on GayHalifax in 2007. “Many of our friends and acquaintances landed up at the V.G. emergency! There was no police support.”

In fall of 1975, the GAE was made aware of a series of queer bashings that happened on the Triangle. By summer 1976, there was another slew of anti-gay violence. Carl Baxter told a GAE general meeting that he had been attacked a total of four times that year. The same bashers went after at least three other victims, one of whom was Metcalfe.

In fall of 1976, Metcalfe met a friend for pizza to commiserate over a recent break-up. Afterwards, walking past the now-demolished Saint Patrick’s High School, someone saddled up beside him and asked for the time. Suddenly someone punched the side of his head. When he turned around, Metcalfe saw four men surrounding him. He swung his bag around, trying to fight the group off, and the next thing he knew he was waking up in the back of a police car. The cops had found him lying in the street, concussed and in need of stitches. The police told him that he shouldn’t be walking in that area—where he lived—and drove him home.

With little other recourse, the gays decided to bash back. Chris Shepherd, who is 6’5” with what he describes as “a big mouth to match,” organized a group to confront the “fag bashers.”

“A number of us had just gotten fed up with the whole gay bashing scene in the city,” says Shepherd. “We put the word out that anybody who was willing and able to stand up and have a fight, and that meant physical confrontation, let’s get to it.”

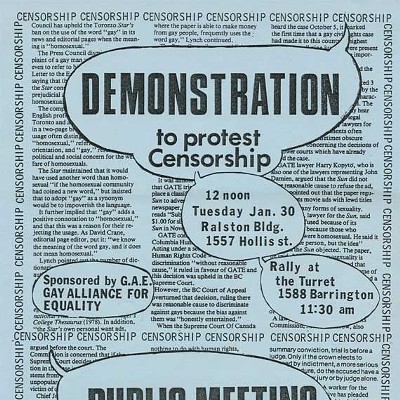

Not all the fights were physical, though. In 1977, a decade before the first Halifax Pride parade, Nova Scotia’s gay and lesbian community came together for its first public protest, picketing CBC headquarters on the corner of Sackville and South Park Streets over the local station’s refusal to run a public service announcement advertising the GAE’s Gayline. The head office in Toronto would later enshrine into national policy the rejection of PSAs from gay and lesbian organizations.

And the CBC wasn’t alone. The Mail-Star also refused to run any GAE promotions. Radio station CFDR said “it would offend its audience,” and asked the GAE whether it had “retained medical personnel who could help homosexuals to cure themselves.”

So, on February 17, 1977, 21 people marched out front of the CBC building. Two days later, activists in five major Canadian cities held pickets to make it the first nationally coordinated gay and lesbian demonstration.

“It’s easy to romanticize in retrospect,” says Metcalfe, of that first decade of gay activism in Halifax. There was still plenty of in-fighting, though—a measure of polarization between gays and lesbians who ascribed to more radical politics, he says, and the men who celebrated “the arched eyebrow and a camp sensibility.”

That culture “clashed with the perceived and often actual humourlessness of the left,” he says. “I wouldn’t even say in retrospect that they weren’t supportive of action, but they would make fun of the lefties, and our earnestness.”

MacSwain acknowledges that some people were probably “miffed by the activism that we brought into the meetings.”

Reg Giles, for one, felt that the GAE should have had no say in the running of the Turret, but rather simply be the beneficiary of the club’s revenue.

“Everything at the bar became too political for its own good,” says Giles. “I miss the camaraderie sometimes,” he says. “It’s something I don’t think any other generation is going to have.”

“The GAE Inc. is operating a counselling phone line for male and female homosexuals. The phone line is for problem-solving, giving out information and for referrals. The hours to call are from 7-10pm Thursday, Friday and Saturday. All calls are strictly confidential. The number is 429-6969.” —A 1977 PSA from the Gay Alliance for Equality that CBC refused to broadcast

tweet this

If you were a gay activist in the ’70s or early ’80s you were a “bonafide subversive,” says Deborah Trask. For a time it felt like being part of a “secret organization.”

Trask’s phone was tapped and she was followed. One morning, the Special Investigative Unit of the Armed Forces (whose raison d’être was to weed out gays and lesbians) showed up at her home. The night before, Trask’s friend and temporary tenant had brought home a lesbian who served in the forces. The SIU also regularly set up surveillance across from the Turret to photograph people going in and out of the club.

“It was an intimidation thing and it got to me,” says Trask. “After awhile it just gets to you.”

The GAE eventually closed the Turret in the summer of 1982, and subsequently opened Rumours on 1586 Granville Street. Rumours would wind up moving to Gottingen Street, where it finally dissolved in 1995 along with the GAE’s successor—the Gay and Lesbian Association of Nova Scotia.

When GALA ceased operations, Lynn Murphy hauled the organization’s papers to a safe and undisclosed location—her own basement—then transferred the files to Nova Scotia’s archives when she downsized into an apartment.

“And I haven’t looked at them since,” she says.

Murphy, who obtained a certificate in archival studies from Dalhousie University, still worries about the historical documents hidden away in other people’s basements. When that person dies, “someone says ‘Oh my god, Uncle Harry was gay,’ and burns them.”

Robin Metcalfe has been squirrelling away LGBTQIA memorabilia since the 1970s—everything from a Heidleberg stir stick to a Turret matchbook. June 1977 minutes even show Metcalfe putting forward a motion to send copies of all GAE minutes to the (then) newly minted Canadian Gay Archives.

All those efforts were born from a desire to avoid the kind of whole cloth elimination of a queer history that was seen in Germany, when the Nazis burned the Institute of Sex Research’s queer and trans library in 1933 and wiped out a catalogue of the German homosexual emancipation movement.

“We never again want to forget our history,” Metcalfe says. “There are many ways that it can be forgotten or erased other than the brute repression of the Nazis.”

Aware of these facts, local elders have made a series of overtures to record, share and enshrine Halifax’s LGBTQIA history: Metcalfe’s 1997 “OUT: Queer Looking Queer Acting” art exhibit and accompanying catalogue; Dan MacKay’s GayHalifax wiki; Reg Giles’ online account of 1970s and 1980s gay life, Peanut Butter and Jam Sandwich (THRU MY EYES); the 2004 Lesbian Memory Keepers Workshop; Chris Aucoin’s Halifax Pride 30th anniversary souvenir magazine and many more.

It’s an invaluable resource for people like myself and other “younger” LGBTQIA and Two-Spirited activists poking around and bugging our elders about the people, places and events from 40 years ago. “The fact that you’re even interested,” says Trask, is part of the GAE’s legacy.

For Metcalfe, today’s activists echo those from the 1970s. A high-octane, grassroots, radical activism that’s reflected in Queer and Rebel Days, the Dyke and Trans March (of which I was a founding member), Rad Pride, South House and all the organizing currently happening within Halifax’s queer, trans, black and Indigenous communities.

“The latest generation of activists has given me hope that there are successors,” he says.

A hope that the torch of liberation, once passed to Anne Fulton, will continue to burn.

Rebecca Rose is a queer freelance writer and community organizer currently living in Halifax. She is a member of the Canadian Freelance Union.