Here are a few things you may notice about Meghan Clarkston when you first meet her. A swath of fiery-red hair and short, chopped bangs framing a pretty, heart-shaped face. The tunnels in her earlobes. An engaging, honest laugh that reveals teeth. Clarkston carries around a large sketchbook. Today, it's open to a page taken up by a charming profile of a woman's face, drawn in ink. It would make a great tattoo.

Here is something you probably won't notice: Clarkston has an eating disorder. But now you will be able to witness her bulimia---it's the subject of her photography that will be on exhibit at Anna Leonowens Gallery next week, part of a NSCAD student group show opening Monday, January 17.

Originally from out west, Clarkston came to NSCAD in 2005 after she graduated from the Victoria College of Art and Design. She wanted to be a photojournalist. In 2008 Clarkston took a year off from NSCAD and went back west to try out the profession, working as a sports reporter, then as an editor. Her project grew out of that interest in photojournalism, and in artists who had documented tough personal events, such as family members dying of cancer.

In September, she started Susan McEachern's Advanced Photo Critique course, a self-directed senior class. It was a small group, only seven, and all women. "Every time you have an advanced class, it's always special," says McEachern. "Students at this level have already determined that they're pretty committed to what they're doing. They've practiced a lot of different things and thought about and explored some things. They're all unique. But this was a particularly strong grouping."

When it came time to discuss individual projects, Clarkston laid it all out. "I said, 'Well, I have an eating disorder and I think I'm going to document the ritual aspect of it.' At the time I didn't think it would be that shocking, but it pretty much shut everyone up, and jaws hit the floor," she laughs quietly. "'Oh, OK, I guess this is kinda big.'"

Clarkston was also surprised by how little her classmates knew about bulimia. "Shocking, given that it's a university setting and everyone's about 24 to 30---they were pretty unfamiliar with it. It was an educational tool as well, I guess."

McEachern approved the project because Clarkston is an adult who knows the issues around her eating disorder, and also because she was under professional care. "My only concern would have been anything to do with putting herself in danger, or her health, and in any way being an enabler," she says. "But we discussed all that as a class, and I think as maybe a group of women in the class---though eating disorders aren't exclusive to women---there was a very strong interest and a feeling of support for Meghan, and a caring for her."

About three weeks later, Clarkston brought the first images to class.

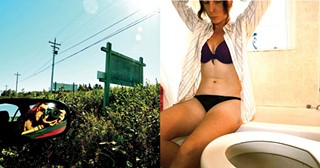

The focus of her work, which will be in the gallery, is a triptych of large photographs. First is a side profile of Clarkston's naked torso, shot against a clinical white background. The second, an image of her distended belly after eating pounds and pounds of food. Three: Clarkston after a purge, holding a clear plastic bag with the contents of her stomach. If there's enough space in the gallery, she'll also include some imagery that portrays her life outside of the disorder.

"It was pretty emotional, I have to say," Clarkston says. "There was some tears and a lot of ahhhs, and there was shock and gasps. At the time I didn't see that." Initially Clarkston believed it was no different than showing an addict on a bender. "It was an everyday occurrence for me, but it showed that it worked: The shock value coming from the photographs."

Her classmate Chloe O'Brien, whose photos detail latex casts of her own skin, agrees that the images are shocking, but that Clarkston "was open and direct and matter of fact, which helped us." Clarkston, though, began to feel guilty: "They're graphic images and I'm asking people to look at them; you can't really turn away from it."

More guilt began creeping in. It was an all-day class, and often there was a potluck, a nightmare for someone with an eating disorder. "I would never eat. I just can't do it," says Clarkston. One of her classmates asked if it was OK if they ate in front of her.

"I can't ask the world not to eat in front of me, but it is challenging for me to not dive in. So they went away feeling bad for the fact that they're doing a natural process, which in turn I feel bad because I can't ask them to not do that," she explains. "It's hard with this topic to walk away without more guilt because I'm making people feel something they shouldn't feel just for being human. That part I'm trying to adjust to as well."

The class continued on. Not only did Clarkston create strong and confrontational work, but other students in the class did as well. For example, KT Lamond is documenting the female-to-male transgender community, "and the ways in which they appropriate their bodies through ritual and routine." Biran Shirazi is exploring her Iranian culture. Other artists pursued projects on death, ecological issues, substance abuse.

McEachern isn't exactly sure how the intensity of projects came to be. "You don't know how these things evolve; if they were influencing each other to have the courage to address some really heartfelt experiences or issues, but I have to say that it was an extraordinary class in that everyone did very courageous work."

At some point, the stress of the project began to affect Clarkston. She was in denial over McEachern's concern that she was going to push herself---Clarkston believed that she had everything under control. But then she experienced a binge-purge phase, where she went almost eight days without eating. Clarkston remembers when McEachern confronted her: "She said, 'I'm going to have to ask you to stop doing this because I'm noticing the difference and you're obviously putting yourself in harm's way.' I hadn't noticed that at all."

Clarkston finished the project immediately. "I was thinking about the artwork, and you don't really think that this vessel is the only vessel you'll ever have and I'm destroying it in the name of art." Her plan is to start treatment right away, this time with outpatient care through the IWK---her first time with in-patient care was back in BC, an experience she found traumatic.

"It's annoying that I have to do it again, it's my 11th year with it, so hopefully this is the last of it," she says. "But at the same time, I'm learning more about myself and asking questions I've never done before because when I photograph myself and then you sit back and look at yourself up on the wall, it's like, 'Uh OK, this is actually really bad---I should stop doing that.' I have to really stick with this."

One of Clarkston's big concerns is that her images could push someone further into an eating disorder. "I realized that if it was me coming in and looking this I would probably think, 'Well, that's not so bad, she doesn't look as skinny I am, or maybe I'm going to be as skinny as her.'"

Although she hasn't seen the work, Cheryl Aubie, a psychologist with Capital Health's eating disorders clinic, agrees with Clarkston's assessment: "The imagery could be pretty triggering rather than empowering." Lena MacLure, a project coordinator with the Eating Disorders Action Group, says the reaction to the show could go either way: "There is a lot of secrecy around disordered eating. There may be some dismay and anger that she is bringing it out of the closet, or it could be freeing---this is the reality of this bizarre behaviour. My hope would be that in seeing these images people would also see the vulnerability, the nakedness."

Clarkston is still struggling to write an artist's statement to stand in when she isn't around. "I feel like I would really like to be there. One, to apologize to people---I feel really bad showing this---and another to explain it." On Wednesday, January 19 there is an artist talk, where all seven students will talk about their work. "I want to convey the message I don't want people to come in and challenge themselves, to think of it as a negative that you should aspire to be."

Anorexia nervosa (controlled eating, usually through starvation), bulimia (repeated binging and purging) and other forms of disordered eating, such as anoxeria athletica (compulsive exercising), are not just about food or controlling weight. According to the National Eating Disorder Information Centre, "People with eating disorders often describe a feeling of powerlessness. By manipulating their eating, they then blunt their emotions or get a false sense of control in their lives."

Once the domain of earnest after-school TV specials, eating disorders do not go away when you turn 18. At the IWK, Aubie says over the past two years the average adult patient is 31, and they've seen patients as young as 10, and well up into their 60s. "Eating disorders can go on for a person's life."

At EDAG, MacLure says their in-person visits are tripled by the number of calls they receive, often from loved ones feeling helpless. "There's a misconception that it's a rich, white community disease, but it hits every gender and ethnic group." Even Clarkston says, "In Halifax, I had never realized how undercover people were with eating disorders. It's a big thing but it's so hidden you don't know about it."

Imagine hiding that sort of secret in a world obsessed with food and physical perfection. Where is your escape, your place of peace? In this TMZ-fraught culture, where parasitic Perez Hilton has made a career out of mocking Hollywood stars in bikinis and a British Vogue editor admits to Photoshopping pounds onto a too-thin model, imagery of the human body is confusing at best. The media, currently more focused on obesity trends, has a habit of only covering disordered eating when there's a celebrity involved. Natalie Portman's rail-thin back heaving over a toilet as she purges in Black Swan inspired the latest discussion about eating disorders caused by the demands and aesthetics of ballet. Then in late December, news of French model Isabelle Caro's death was released. Caro, if you remember, appeared naked on a "No Anorexia" billboard during Milan Fashion Week in 2007, bravely revealing a horrifyingly emaciated body, reminiscent of an Auschwitz victim.

According to Aubie, these media stories aren't always helpful. "Public discussion is positive," she says, "but the media often uses more extreme examples and imagery." Most people with eating disorders don't wear their symptoms like Caro, so those at earlier stages of the illness may believe that if their body doesn't look like those extreme images they're still OK and in control.

When actor Portia DeGeneres revealed her "anorexia nightmare" on the cover of People, she was applauded for her braveness, but some in the ED community see her confession in a different way. When DeGeneres appeared on Oprah, "We cringed," says MacLure. "She actually gave away tips."

But like violence, it's too easy to blame media imagery as a singular cause of disordered eating. Clarkston's anorexia (which later became bulimia) was initially triggered after her father passed away.

"My family had become number one, and there was no time to eat. I didn't mean to do it, but at some point, someone told me I looked great because I had dropped 50 pounds. I was, 'Oh OK, this is good.'"

MacLure says that often disordered eating overlaps with obsessive-compulsive behaviour. Some studies have linked general anxiety disorders, as well. Clarkston also occasionally self-mutilates---there are photos of oozing welts on her legs---and one doctor even speculated that she may be in early onset agoraphobia, when she lost the desire to be social and leave her house.

"I don't know if any of us can pinpoint that epicentre of when it transpired," Clarkston says, "but I know that we all want out. It's hard, you feel yourself dying and you know it's bad."

"I don't want this anymore," Clarkston says with finality.

It's a fact she's expressed in several online support groups. Surprisingly, not everyone in those forums wants to hear that, and Clarkston's been asked to leave several times. "I think it was the fourth group I was kicked out of because I'm really opinionated," she says. "I think a lot of people in these support groups are really comfortable in the disorder and really don't want to get out. Whereas I want full recovery."

So Clarkston started her own blog, Laughter Silvered Winged. If she comes across as emotionally detached from her condition in person at all, it's here where you begin to understand the depth of her hidden pain.

"I started to blog just as a way for express my feelings and my daily struggles and show what I was eating, what I couldn't eat," she says. It's also where she posted the art project images. Once the Anna Leonowens show is over, she plans to continue using the blog as a forum for her work. "I'd like to have another gallery show down the line to incorporate the eating disorder, the self-mutilation and the out-patient recovery."

Clarkston imagines images of doctors and checkups, and has an idea to turn photos taken from a gastrointestinal camera into a collage. "I know my esophagus has been torn once. My stomach has a problem, it can't drain, I can't digest food properly; it takes about 18 hours now for me to digest a meal, because I severed a nerve. I want to try get those images to show people. Because when you talk about it, I mean, you can't see any of that and you can't feel it and I can't express it, but when I eat, it just sits there trying to digest---seriously feels like someone punching you in the gut. I think the blog is the platform to show all this imagery."

Like her art, Clarkston's blog is a rare find: Many eating disorder websites are pro-anorexia, promoting eating disorders as a lifestyle choice. These sites claim to offer support, but then feature model photos for "thinspiration" and tips for hiding weight loss. Some of Clarkston's friends have personal blogs, but keep them private. Her public honesty has inspired others to document their own conditions; she also gets emails from people looking for help, which she happily provides, but says it's overwhelming to hear from someone who is suicidal.

Occasionally Clarkston's received death threats, too. "That I didn't really expect. I try to understand it from that traumatic teenage girl perspective: 'You've just opened the door to this huge secret and now everyone knows and now my mom thinks I have this and blah blah blah...' Well, they're going to figure it out eventually, or they already have but they haven't figured out how to address you about it. I think I'm doing a good thing, and I'm going to keep doing it."

Advanced Photo Critique Show, January 18-22, Opening reception January 17, 5:50pm, Anna Leonowens Art Gallery, 1891 Granville Street, Artists’ talk, Wednesday, January 19, noon

For more information:

Capital Health Eating Disorder Clinic

473-6288, cdha.nshealth.ca

Eating Disorders Action Group

443-9944, edag.ca

The Self-Help Connection

466-2011, selfhelpconnection.ca

National Eating Disorders Awareness Week is February 6-12. For more information contact the National Eating Disorder Information Centre, 866-633-4220, nedic.ca.