Last column I wrote about HRM's plan to sell our toxic crap to farmers, call it fertilizer and grow our food in it. The sludge from our harbour is a massive cocktail of mostly unidentified chemicals that pose deadly risks to farm animals and humans and huge financial risks to farmers.

I've heard better ideas, and this week I'm going to share some.

Maureen Reilly is full of better ideas about liquid waste. She has been researching the topic for 12 years. She expresses frustration that after a decade of fighting the application of sludge on farms, this bad idea keeps resurfacing like a stubborn patch of poo-encrusted thistle.

"It's one big old boys' club," she says of the sewage industry---both its private sector and government manifestations. "There are so few sewage people with so much money, because most people don't like to think about sewage."

As a result, she says, the crap barons rub elbows a few times a year and celebrate every chunk of mud in the public's eye and every new technology crushed. Yet new technologies do abound, with benefits for municipalitites sage enough to invest in them.

A few years ago, St. Paul, Minnesota, decided to buy an incinerator, romantically called a "fluidized bed gasifier." While incineration may raise some green neck hairs, the emissions that result are lower than if the waste was land-applied, with no output of mercury or thallium. This technology reduced the city's emissions by 90 percent, saved them $4 million annually and reduced neighbour complaints from 70 to two per year.

Yet Reilly recommends a different approach for Halifax. "A properly lined landfill with methane recovery is likely best for a city of Halifax's size," she says.

By mixing solid waste with sludge at a ratio of seven to one, leachates can be eliminated. Methane can also be trapped and used as a power source, saving energy and preventing greenhouse gas emissions (because it replaces the burning of fossil fuels).

Alternatively, sludge could be converted into synthetic fuel. Reilly estimates that sludge has about half the energy of coal. This could be sold onto the power grid,further reducing our suicidal climate change tendencies.

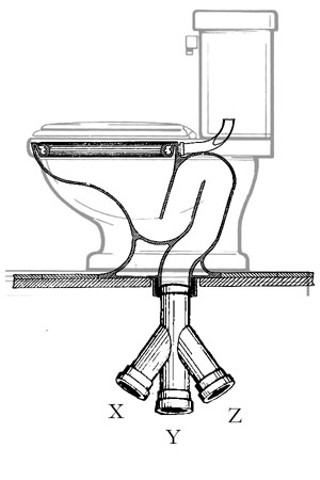

None of these ideas have been given much thought in HRM, so maybe it's too much to ask that we go even further and consider how we could prevent the sludge dilemma upfront. As Reilly points out, the terrible technology of mixing fecal and industrial wastes has been with us for centuries, so maybe it's too soon to hope for onsite septic systems that separate waste-streams.

In HRM, it's hard to imagine the use of large-scale greywater re-use, solar-aquatic sewage facilities or planning systems that integrate green spaces and wetlands into sewage planning. Maybe it shouldn't surprise me that a friend of mine has been trying for over two years to get approval for a smaller septic tank (to accompany his eco-efficient composting toilet) from inflexible bureaucrats with no policy and no clue about newfangled greenthink.

And any hope for phasing out the use of household and industrial toxins is blurred by the setting sun on a distant horizon. And so, for now, we're left with a myriad of options that are better than eating our own waste, none of which are being considered bythe HRM.

If the city gets its way, thallium-enhanced milk will soon be available at your local grocer. All that's needed is Canadian Food Inspection Agency approval.

Kate Billingsley, acting national manager of CFIA's fertilizer section, couldn't discuss Halifax's application to sell sludge, or even whether we have submitted any of the tests required to gain approval of sale. "I can only tell you that the Halifax product has not receiveda 'no-objection-to-sale' letter from CFIA,"she says.

"CFIA acts like contamination levels are secret," Reilly says. "So did you get your thallium today?" Nobody knows.

Reilly feels that if we are to get past the age of sludge-dumping on farms, the chemical composition of sludge needs to be made public. "We need baseline thallium tests on the milk," Reilly says. "The public deserves to know the full cost."

Maybe then we could get started on those composting toilets.

Send the latest poop to [email protected].