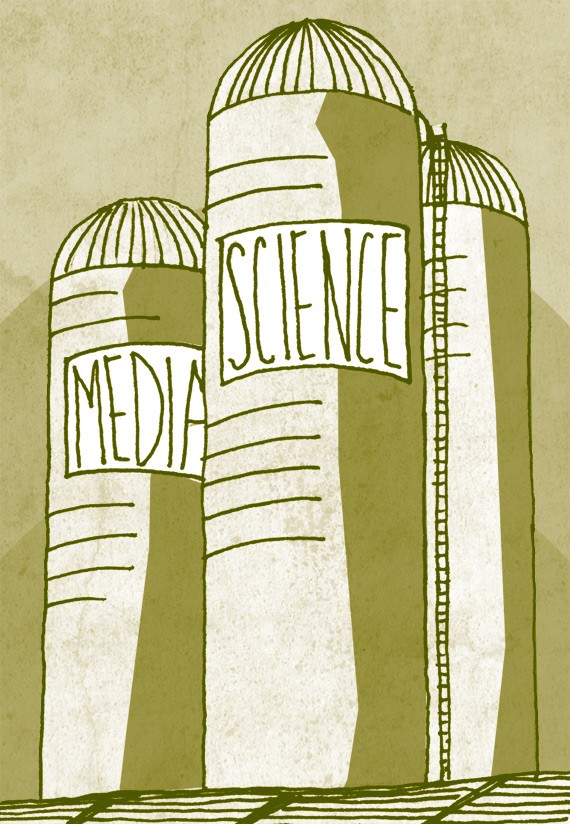

"We have two silos," says meteorologist, broadcaster and author Richard Zurawski. "Scientists communicate with scientists and assume society is interested, when really they view science as unimportant or esoteric."

The other silo is the media, "skewed by ratings wars." Zurawski says its inability to deal with science is the worst it's been in decades: "Reporters lack scientific background and scientists are portrayed as goofballs."

Zurawski explores the devolution of science in the media in a new book, Media Mediocrity: Waging War Against Science (How the Television Makes us Stoopid!). "How is it possible for one of the largest news broadcasters in the world, CNN, to dismiss its entire staff of science reporters without a murmur in the ratings?" he wonders.

Zurawski reviews how the journalistic method's obsession with giving equal play to opposing viewpoints, no matter how absurd the doublespeak of either side, coupled with severe corporate influence via advertising dollars, has hurt the public.

The research on the dangers of smoking by "thousands of scientists over decades could be almost totally marginalized by the journalistic approach of a single reporter," he writes. "Scientists spent most of their time countering straw men and answering a barrage of spurious questions."

And the media, with its fundamental need for conflict, played into a false debate on the veracity of the research. In recent years we've seen the same response to human-caused climate change and the dangers of pesticides. There is no scientific debate on these topics---only a political one played out in the media and generated by spin doctors.

Locally, Zurawski---once a meteorologist with ATV---cites fisheries management. When scientists rang alarm bells about imminent collapse, "the media focused on the fact that fishers on the east coast would be devastated economically if the fishery was closed, and so the governments of the day decided to squeeze off funding for research by scientists." The Harper government has done the same with Environment Canada and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

Zurawski argues that the media doesn't understand the language of science. To reporters and producers, "'very likely' means it is not 'proven,'" so someone disagrees and must be given equal play, despite overwhelming evidence generated by the most meticulous method of factfinding.

Most of the media functions as if it is objective, like a story can be told without bias. This is its fatal flaw. Rather than rigorously seek truth, it haphazardly throws together opposite opinions and calls it balanced.

Television, the closest we come to being there, is especially guilty of generating false debates as entertainment. Initial hopes that easy access to information online would undo the mainstream media's damage have been dashed.

"Rather than TV being superseded by the internet," Zurawski writes, "the internet is evolving TV into an even greater social force...the variation in news sources and the separation between print, television, radio and the internet that existed even a decade ago is gone."

Media are consolidating in two ways: companies are merging into bigger enterprises, and content is being perpetually recycled from medium to medium. The remaining big broadcasters (in Canada that's CBC, CTV and Canwest Global) turn television newscasts into words on the screen and embed the visuals. On the flipside, "news can be culled from print and the internet and repurposed for television."

Science coverage is perhaps the media's weakest point, but its inability to move beyond "accurate" and into profound, complex, comprehensive and truthful reaches into politics and business. The issues are more complex than the media format: short, snappy, tense and zinger-laden.

That's what we, the people, want. "It's a Bayesian world about whatever hits you upside the head," Zurawski says. "Haiti? The Japanese tsunami? Forgotten. We're onto the Greek crisis, which will also soon be forgotten."

We respond to the obvious, immediate threats in our environment---a great survival strategy if you're stalked by hungry cougars, but limited when a population of seven billion and the proliferation of cool gadgets are the things most likely to snuff us out. The media amplifies our obsession with now.

Zurawski doesn't expect to reform the media---he wants people to better understand its limitations. "We need to start re-examining our priorities and better understand the influences on the media."

Chris Benjamin is the author of Drive-by Saviours, a novel; and Eco-Innovators: Sustainability in Atlantic Canada.