Yesterday, we heard two prisoners at the Nova Institution federal prison for women in Truro were awaiting results on COVID-19 tests. Fortunately, by early afternoon, it appeared both were negative— spared for now from being added to a list that's being compiled by Justin Piche at University of Ottawa.

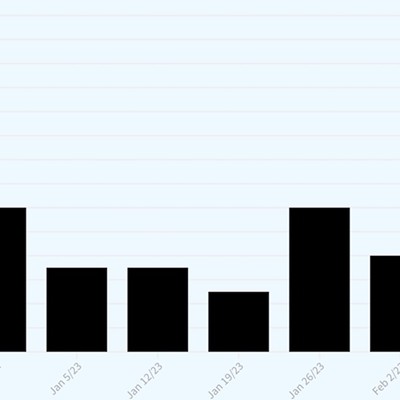

Piche is tracking positive coronavirus cases in carceral institutions across Canada. So far, there are 52 positive cases in the federal system, and it is only a matter of time until one is identified in Nova Scotia. (At the Joliette Institution for Women in Quebec 33 guards and at least 10 prisoners have tested positive for COVID-19).

Five weeks ago I first wrote about the danger COVID-19 poses for incarcerated people here; in the weeks since we have seen countless articles covering both the risk, and the response, to COVID-19 in prisons across the globe. New York’s Rikers Island jail alone has over 600 positive cases, including the deaths of four correctional officers and one prisoner. Many jurisdictions, including the Province of Nova Scotia, are heeding the warnings issued by health care professionals and depopulating prisons to ease the burden in these crowded and unhygienic spaces. Correctional Services Canada, however, has yet to release any federal prisoners to prevent COVID-19 transmission, despite existing federal legislation that would allow for doing so.

As a registered nurse working in the area of reproductive health and criminalization, I am most concerned about how COVID-19, and restrictions for its containment in prisons, will disproportionately impact women, trans/nonbinary parents and pregnant people. The gendered experiences of health and care require a gendered lens to how we approach COVID-19. In Canada and specifically Nova Scotia, this lens must also address discrimination, colonialism and racism.

Earlier this week, the United Kingdom announced six mothers and their children would be released from the “Mother Baby Units”, where incarcerated mothers there can live with their infants. Around the world, it is common for mothers to be co-incarcerated with their children. Canada has a Mother Child Program, where children up to age five live with their incarcerated mothers, in each of the six federal prisons for women across the country.

Truro's Nova Institution hosts such a program. The program is rarely used; of the roughly 675 people in federal women’s prisons on a given day, a half dozen might live with their children. The program was conceived decades ago as stop-gap to address the cascade of social and familial harms associated with increasing incarceration of women. Most incarcerated women are mothers. Forced separation from their primary parent is traumatic for children. Mothers are also traumatized: having their children removed from their care is associated with elevated rates of anxiety and depression, substance use, custody loss, suicide and mortality. Co-residence supports bonding, parenting continuity and health. But prisons are dangerous, and co-residence is a fraught compromise at the best of times. During a pandemic there is no question: these babies, and their mothers, must be released.

Their releases would pose low risk to the public; in fact, these mothers and babies are part of our public, and require protection. Mothers who qualify for the co-residence program already must meet strict eligibility criteria, including qualifying for low-level security classification at the institution and submitting to surveillance by provincial child protection authorities.

To allow these mother-baby pairs to be subjected to the risk posed by COVID-19, or worse, to separate mother-baby pairs, is unacceptable. Prison now is untenable. Prisoners experience mental and physical comorbidities (when someone experiences two or more chronic diseases or conditions at once) that exacerbate their risk of serious infection. They are facing the fear and isolation we all are feeling, but doing so under threat of use of force, without access to internet or information, and with no control over basics like their own food and hygiene.

Prisons in Canada grossly over-incarcerate Black, Indigenous, and people of colour. We already have clear data from the United States that shows the lethal impact of racism intersecting with COVID-19. We have clear direction from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the National Inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women that decarceration is a minimal requirement towards justice in this country. Now is the time.

COVID-19 is causing a global reckoning about accountability. We are realizing our actions and their consequences for the collective are complicated and intertwined. Part of that collective is imprisoned. We are all adjusting to a radical new normal: accepting massive shifts to our financial, social and psychological stability to keep our community well. We can do justice differently. During COVID, and after, too.