That amount, plus the $160,000 or so that Kelly had transferred from Thibeault’s personal bank account to his and his son’s control (see “A trust betrayed,” February 16), reflected the fruits of Thibeault’s labours as owner of the Prince’s Lodge Motel, which she and her husband Joseph bought in 1945. (Joseph Thibeault died in 1984.)

The motel was at 554 Bedford Highway, about 200 meters north of the Rotunda. Thibeault’s property had been carved out of the old Prince’s Lodge, the sprawling estate that Nova Scotia governor John Wentworth allowed Prince Edward to use in 1794 to host his mistress, Julie St. Laurent.

Thibeault’s property was in two sections. The first section was a “water lot,” reflecting the pre-Confederation practice of granting title to property largely under water, and totalled about 1.7 acres. It consisted of a small strip of land---about 5,000 square feet---to the east of the highway, which was bisected by the CN tracks, with the remainder---about 67,000 square feet---under the waters of the Bedford Basin.

The motel itself sat on the second section of Thibeault’s property, which consisted of 8.61 acres to the west of the highway. The property rises dramatically from highway, affording stunning views of the Basin and of the MacKay Bridge.

The property was first surveyed in the 18th century, and consists of three parcels. Some subsequent owner bought all three, and they’ve been sold together as one property ever since. The property was nearly square, with the motel sitting directly on the northern property line.

Zoning problems

In the 1970s, there was renewed interest in what remained of the old Prince’s Lodge property, much of which sat behind---to the west of---Thibeault’s land. The former city of Halifax began buying up what land was available, and pieced together Hemlock Ravine Park. The city also took efforts to buffer the new park from possible nearby uses, and so in 1978 zoned 3.5 acres on the western part of Thibeault’s property “Park and Institutional”---effectively prohibiting any development of that portion of the property.

Zoning is a city tool to control what kind of uses property owners can make of their land, and so largely determines property values---and potential sale values. Because zoning is intended to protect nearby properties, zoning changes legally can not be made without a public hearing before city council, and a public vote by council.

Last year, The Coast asked the city’s information officer for access to the planning files for 554 Bedford Highway; we were given just three documents related to the property. But as our investigation continued, we happened upon Rick Gagne, who lives on Lodge Drive, a short residential street to the south of Thibeault’s property. Gagne was a founder of the Prince’s Lodge Residents Association, which was formed in 2000 out of concern over the development of the old motel property. In that capacity, Gagne had amassed hundreds of documents, including scores of city planning documents related to the zoning of Thibeault’s land.

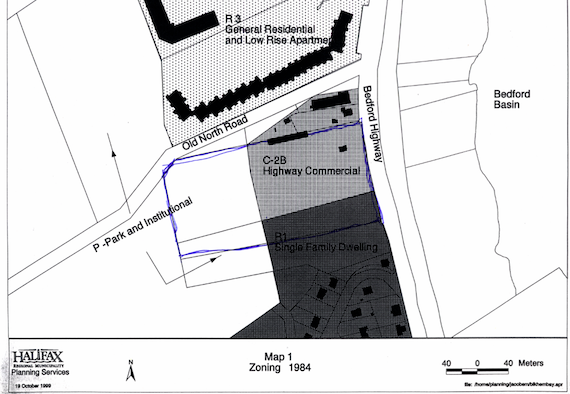

Those documents and other records reviewed by The Coast show that zoning placed severe limitations on what kind of future development could happen on the site. Besides the Park and Institutional zoning to the west, in 1985 the southern portion of the land was zoned Low Density Residential, called R-1, which allows only the construction of single-family detached homes. The portion of the property zoned R-1 corresponds with the southernmost of the three parcels surveyed in the 18th century.

The two northern parcels of Thibeault’s property were zoned Highway and Commercial, which allows the construction of retail establishments, office space and high-density apartments---albeit the western portions of all three parcels had the Park zoning.

The three zoning designations for Thibeault’s property are clearly shown on two city planning maps---a 1984 map that was reprinted in 1999, and a 1990 map drawn to discuss a possible city purchase of some of the land. Here's the 1984 map, with the Thibeault property outlined in blue:

The three zoning designations are also discussed at great length in multiple communications between Thibeault’s lawyer, Lloyd Robbins, and city officials, and by city officials between themselves, starting in 1988 and extending to 1995.

“Exceptionally low price”

For example, on January 27, 1988, the city’s development administrator, W.B. Campbell, wrote to four other city officials in the parks, real estate and planning departments, concerning Thibeault’s property and an adjacent property, which also had similar zoning restrictions. Campbell explained that a city development officer, Mike Woods, was “getting a lot of pressure” about the zoning. “Those owners have had difficulty getting firm values on their property and consequently, are finding it hard to market them due to the existence of a large piece of Park and Institutional zoning and open space designation at the rear of the properties,” wrote Campbell. “Basically, they would like us to buy the land or let them use it.” Woods thought an offer of $15,000 per acre on the Park land was a reasonable price.

City officials knew that the zoning on the site was an obstacle, and negotiations with Robbins continued for several years. Robbins argued that the Park zoning of private land amounted to “expropriation without compensation,” and in fact such zoning became illegal in 1983; therefore, argued Robbins, the city should buy the rear portion of the property at a price set as if it were zoned for commercial uses.

Alternatively, said Robbins as early as 1991, the city should buy the entire 8.61 acres---for $600,000. That price, noted Woods, “purportedly equates to an earlier offer from a client unknown to me.”

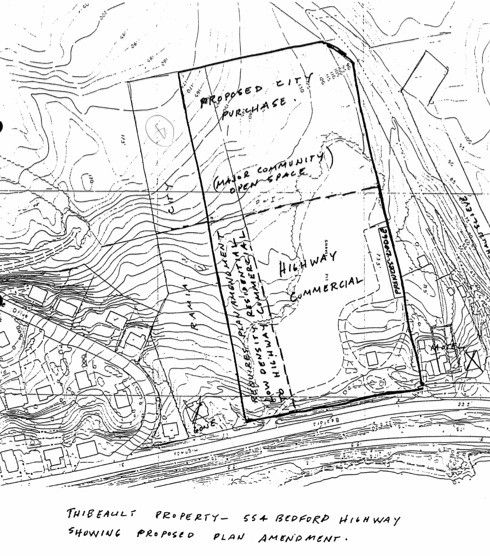

The map in the city file, which is labelled as from 1990, shows the zoning restrictions on the property. It is consistent with the 1984 map above, and with all the documented exchange between Robbins and the city:

The western part of the Thibeault property, zoned Park and Institutional is at the top of the map, and is labelled "proposed city purchase (major community open space). The southern part of the property, at left, is labelled "requires plan amendment-- low density residential to highway commercial." The remaining parts of the property, already zoned highway commercial, are at lower right.

On June 2,1995, Thibeault wrote to Wayne Anstey, then the city solicitor, and offered to sell both parts of her property---the motel land and the water lot---to the city, for $700,000. This was “an exceptionally low price,” noted Woods.

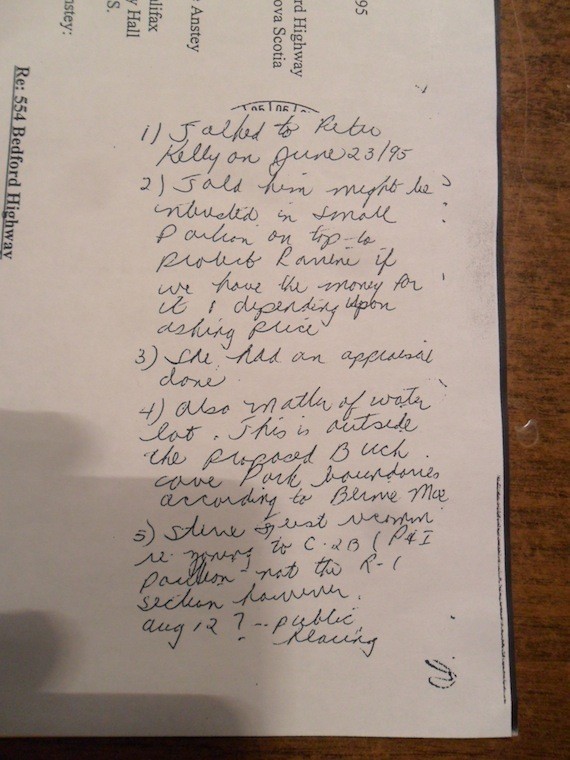

On Thibeault’s letter to Anstey there is a hand-written note:

It reads:

1) Talked to Peter Kelly on June 23/95The hand-written note, which is initialed but illegible, clearly indicates that the city did not want the R-1 zoning on the southern portion of the property changed.

2) Told him might be interested in small portion of top to protect Ravine if we have the money for it & depending upon asking price

3) She had an appraisal done

4) Also matter of water lot. This is outside the proposed Birch Cove Park boundaries according to Bernie Moe

5) Steve Feist recommends re-zoning to C-2B (P&I portion---not the R-1 section however. August 12 ? ---public hearing.”

On August 20, 1995, Peter Kelly, then mayor of the town of Bedford, appeared before the Halifax city council, “representing Ms. Mary Thibeault,” according to the minutes of the meeting. Kelly asked that all of Thibeault’s property be rezoned Commercial. “Responding to Mr. Kelly’s comments, [development official Stephen] Feist indicated...that a rezoning would require that Ms. Thibeault apply for such and that a public hearing be held.”

The water lot

The water lot took on a trajectory of its own. “The water lot is situated approximately 1,000 feet north of Prince’s Lodge, which is the northern boundary of the proposed Birch Cove Park,” wrote R. Matthews, the director of planning, on June 19, 1995. “As this is beyond the scope of the study area at this time, it is recommended that the city not pursue acquisition.”

That view was reiterated on July 18, 1995, in a letter from Mike Woods to Mary Thibeault. “The city would also not be interested in purchasing the water lot as it is beyond the area under consideration for Birch Cove Park,” he wrote.

The city council for the former city of Halifax did not discuss the Thibeault property or the park issue over the next nine months---until the city ceased to exist and was amalgamated into the Halifax Regional Municipality on April 1, 1996. And yet, on October 21, 1997, the city council for the new city of HRM agreed to buy the water lot for $23,304.90. “The former Halifax Municipal Development Plan and the Parkland Strategy support the acquisition of the Thibeault property for parkland purposes,” explained a staff report written by Larry Corrigan, the commissioner of Corporate Services, directly contradicting Matthews and Woods from two years earlier.

Peter Kelly, then an HRM councillor representing Bedford, abstained from the vote on the purchase of the water lot, noting that he had represented Thibeault in the rezoning request.

Deal / No deal

As for the motel property, the city and Robbins were working towards a possible compromise. Robbins argued that the city didn’t need all of the 3.5 acres zoned Park in order to protect Hemlock Ravine, but could get by with a smaller portion, and there could be a deal whereby all the remaining motel property---including the remaining land zoned Park and the land zoned R-1---would be rezoned Commercial, which would allow Thibeault to sell at a higher price.

But the city wasn’t interested in changing the R-1 zoning. In his July 18, 1995 letter to Thibeault, Mike Woods makes a counter-offer, offering to buy two acres at the rear of the property for $38,000. “The balance of the area zoned P&I, excluding the R-1 portion, will be recommended for redesignation to Highway Commercial (C-2B) at a Public Hearing on 23 August 1995.”

The public hearing never happened, and on October 4, 1995, Thibeault wrote Woods to reject the $38,000 offer because it “is below the market value of its Commercial Land Designation.”

And there the matter dropped. Neither city---not the former city of Halifax, nor the new city of HRM---would buy any of the motel property, and neither city held a public hearing to rezone any of the motel property.

It’s important to note that through all of this, while the city officials entertained the idea of buying at least a portion of the west part of Thibeault’s land that was zoned Park and Institutional, they were adamantly opposed to rezoning the southern portion of her land that was zoned R-1.

Thibeault sells her property

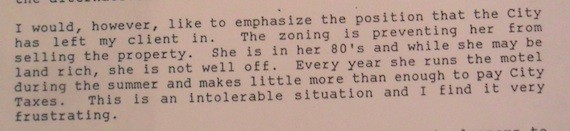

Mary Thibeault very much wanted to sell her property. In 1992, her lawyer Lloyd Robbins told city officials that “The zoning is preventing [Thibeault] from selling the property. She is in her 80s and while she may be land rich, she is not well off. Every year she runs the motel during the summer and makes little more than enough to pay city taxes. This is an intolerable situation and I find it very frustrating.”

At the time of the letter, Thibeault was actually not quite 80---she was 78, but she was operating the motel by herself, without any employees. She worked the spring through fall, then wintered in St. Petersburg, Florida, where she owned a small trailer in the Venetian Homes Mobile Home Park.

Robbins had told city officials in 1990 that there was a $600,000 offer for the motel property, and in 1995 Thibeault had offered the property to the city for $700,000.

Thibeault had rejected the city’s offer to purchase two acres of the rear of her property on October 4, 1995. Two years later, on October 7, 1997, she entered into an agreement to sell the property to developers Nassim and Solomon Ghosn, for $600,000. The Ghosns intended to build three apartment buildings on the site.

The Ghosns’ purchase of the motel property was conditional---they gave Thibeault a $10,000 deposit, good for six months. Final sale was “subject to the [Ghosns] negotiating and obtaining a Development Agreement with the Halifax Regional Municipality.” Similar conditions involved getting provincial approval for an on-site sewage system, getting Halifax Water to agree to service the property and getting financing for the new development.

But the Ghosns weren’t able to line up all the approvals for development by the end of the six months, so on April 3, 1998 they paid Thibeault another $10,000 deposit to get a six-month extension.

Finally, on October 2, 1998, the sale was completed, between Thibeault and a numbered corporation controlled by the Ghosns.

City approves apartments

Another six months later, on April 29, 1999, HRM issued a development permit to W.M. Fares, to construct a 72-unit apartment building on the former motel property the Ghosns had purchased. (By this time they had renamed their numbered corporation “Prince’s Lodge Estates Incorporated.”) The permit says that all 8.61 acres are zoned C-2B.

In their agreement with Thibeault, the Ghosns made quite clear that they needed a development agreement with the city to build apartment buildings on the site, probably because such a project would need two zoning changes. Development agreements must be approved by city council. But the building permit that was ultimately issued for the first apartment building was issued “as of right,” meaning that the project satisfied the terms of zoning, and there was no need for council approval. But this was not true---the zoning did not permit apartment buildings.

Still, the permit also contained the usual fine print: “It is the applicant’s responsibility to ensure the site plan provided accurately describes the subject property,” reads the development permit. “Approved pursuant to the R-3, General Residential and Low-Rise Apartment Zone requirements as permitted in the C-2B, General Business Zone, in the Bedford Highway Area of the Halifax Mainland Land Use Bylaw. This application was not reviewed in respect to future subdivision.” That is, the city tries to claim it’s not responsible if it issues a building permit for something that isn’t zoned for the site.

The R-1 zoning issue was never resolved---there had never been a public hearing about a change in zoning, and city council never voted to change the zoning. In contradiction of land use policies and provincial law, city staff had approved construction of an apartment building partly on land zoned for single-family detached homes.

Over the next few months, the city issued other permits related to the property, including demolition and blasting permits. In the summer of 2000, the developers clear-cut much of the forest on the property, and began blasting to remove a substantial amount of rock. That work drew the attention of the neighbours.

Neighbours fight building

“With Ghosn developing the property, the site was clear-cut; that raised a whole lot of eyebrows, particularly among people who were naturalists,” says Rick Gagne, who lives on Lodge Drive, the street just south of the old motel property. “And as a hydro-geologist, I’m fully aware and was very concerned for the potential for impacts the blasting could have on our water supply. We were on wells and septic, and the concern back then was---I had a rough idea of what it would cost to bring services up here---so in an effort to try to preserve what it was that we had, we had to stop the blasting, and make sure that somebody was going to take on the liability for the blasting.

“They were doing quarry-style blasting,” he continues. “If you look at the back wall of the property, there’s about a 40-foot wall---that wasn’t there before. That 40-foot wall was created by blasting. This was not typical construction; this was quarry scale. They were doing all of this with no regard to any of the water supplies around them, or the buildings around them. No pre-blast surveys had been done, in keeping with the then-Halifax blasting bylaw.”

Gagne brought his concerns to Paul Dunphy, a development official with the city. As Gagne tells it, “[Dunphy’s] response to me, and I remember his words, were: ‘It was never the intent of the blasting bylaw to provide the level of protection that you are seeking.’ Now, why have a blasting bylaw there in the first place, was my question to him, and he said, ‘We’re done with this conversation.’ I said, ‘OK, that’s good, because I’ve recorded this conversation,’ which I did.”

With construction of the apartment buildings moving forward, two community groups were formed---Friends of Hemlock Ravine, concerned that clear-cutting related to the construction would diminish the buffer between the development and the park, and Prince’s Lodge Residents Association, formed by 52 nearby property owners out of concern that blasting would adversely affect their wells and septic systems.

“We realized, OK, HRM doesn’t seem to give a damn about the bylaw,” says Gagne. “But we learned of the zoning, and the footprint of the foundations for the buildings was encroaching upon the R-1 land. So we said, ‘Let’s put a stop to this on the basis of the zoning.’”

Stop work / Go work

On July 27, 2000, in his capacity as president of the Prince’s Lodge Residents Association, Gagne served legal papers against the city’s building officer, threatening to sue the city for allowing blasting without a pre-blast survey and for allowing construction on an apartment building on land zoned for single family homes.

The next day the city issued a stop work order on construction of the apartments, and issued a press release explaining the action:

The action was based on new information provided to HRM that the 72-unit building under construction was being built on two lots---not the single lot as earlier indicated.. However, all the land in question is owned by the company.That press release accurately reflects the legal status of the property, as documented in multiple planning maps stretching back decades, and as conveyed in repeated letters from city staff to Thibeault and her lawyer over a 10-year period.Based on the information submitted previously, HRM understood that the land holdings of the owner on the Bedford Highway consisted of a single lot.

Municipal records showed that the land identified at this location was zoned appropriately to permit construction of an apartment building and, on that basis, a Building Permit was issued.

However, HRM learned recently that the land in question appears to be made up of two lots, and that the southernmost is zoned R-1 (which does not permit the construction of a multi-unit building).

But just a week later, on August 4, 2000, the stop work order was lifted, and the city issued another press release:

The builder has now met the requirements of the subdivision and land use by-laws by consolidating their properties as one lot. As a result the building is now properly located on one lot. A review of all relevant property and zoning information has led to the determination that the entire building is located in the correct zone. The building complies with all municipal requirements.The explanation in the second release doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

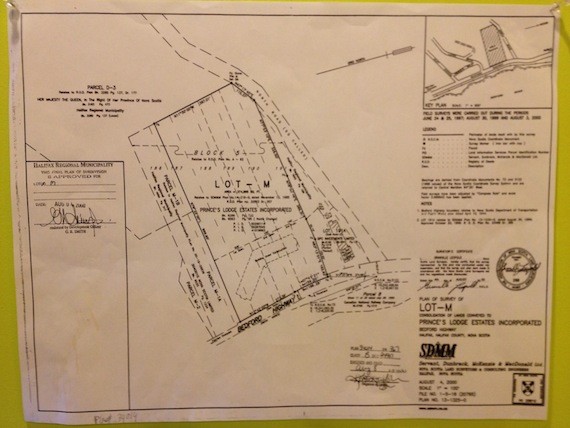

It’s true that a subdivision map for the property was presented to the city on August 4, 2000. Here it is:

Note that three (not two) constituent parcels were consolidated into one lot. But the map clearly shows that the southernmost “1st parcel” extends 206 feet from the southern property line. And by comparing the map with those above, you can see that part of the apartment building sits on the R-1 zone created in the 1980s.

Avoiding a law suit

Upset that the stop work order had been rescinded, the Prince’s Lodge Residents Association asked for a meeting with the city, and a person who worked in the planning department, met with the group.

“[The planner] explained to us the following,” says Gagne. “The reason the stop work order had been rescinded was that the developer was preparing to sue the city, because they had issued the building permit, and ought to have known that it was zoned R-1 and denied the building permit on that basis, but they [issued] the building permit in any case.

“Rather than deal with this matter, the city hired the developer’s surveyor to research the location of this zoning boundary---apparently the exact location was obscure in history,” continues Gagne. “[The planner] told us that HRM had elected to choose the boundary of convenience---‘location of convenience’ was the phrase she used---to avoid a legal suit by the developer. She said, ‘That puts you, as residents, in a position where you can sue the city, because this boundary location is still disputable, however, we are less concerned about you guys suing us’---because back then class action suits were not allowed in Nova Scotia---and she said, ‘you’d have to sue us individually, and we don’t expect to see 52 individual suits. So we’re less concerned about you then we are about the developer, and we’re taking the approach of least risk.’ She told us that point blank. She was honest with us.”

But the boundaries of the three underlying parcels that comprised the motel property---and therefore the zoning boundaries---are not obscured in history. First, field descriptions of the three parcels are contained in the property’s deeds, including the deed that accompanied the Ghosns’ purchase of the land from Thibeault. Second, the three parcels are distinctly drawn, and labelled as such, on the subdivision map that was submitted to the city in order to merge the three parcels.

No one to blame

There’s no satisfying explanation for why the zoning of the property evolved the way it did, and without access to the city’s legal file, it’s impossible to assign blame. (The Coast has requested the legal file, but the city declined to make it available.)

There’s a paper trail of dozens of documents leading back to at least 1988, with officials from the planning department, the park department and the legal department all making clear that they had no intention of recommending zoning changes for the property, and that such changes would need approval by city council in any event.

And yet, by 2000 all the zoning problems were washed away, with a new site map that completely contradicts three previous site maps---without council approval, and seemingly with a wave of the bureaucratic hand. It’s possible that there was a system breakdown, and all the multiple actors unintentionally screwed up in precisely the same manner---but is it really possible that the entire city bureaucracy across three departments made the same mistake at the same time without coordination?

Regardless, the end result is that because she could not sell the property at commercial zoning rates, Thibeault lived out her last years in relative poverty.

With the complex zoning, there was little potential for development, and that is reflected in the assessed values for the property. In 1995, the year Thibeault asked the city to buy the property for $700,000, it was assessed at $239,800.

While property values in Rockingham were doubling and tripling through the real estate boom of the 1990s, and annual increases of 20 percent were not uncommon, the value of Thibeault’s property was flat. In 1998, the year she she sold it to the Ghosns for $600,000, the property was assessed at just $246,100---a three percent rise over three years.

But after the zoning was changed and apartments built, the assessed values skyrocketed. This year the property is assessed at $22 million.