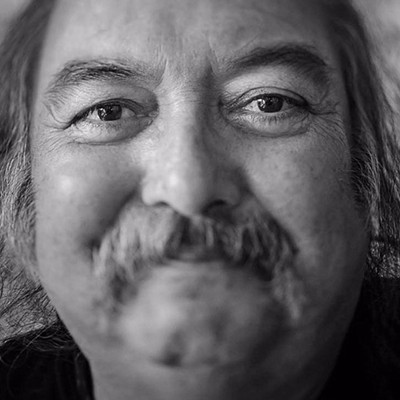

Andrea Dorfman moved from Toronto in 1993 to attend NSCAD. Her 2000 feature debut Parsley Days screened at the Toronto International Film Festival as well as the Atlantic Film Festival, where Love That Boy (2003) and the documentary Sluts (2005) had their premieres. Dartmouth native Jason Eisener: co-wrote and directed the fake trailer for Hobo with a Shotgun, which won the Grindhouse competition hosted by Robert Rodriguez last year. A Hobo feature is in development. His Treevenge will screen on opening weekend at the genre festival Fantasia in Montreal this July. They spoke before an early evening screening in the balcony of The Oxford.

Eisener:: I think the first time I met you I was in the Screen Arts program .

Dorfman: What year would that have been?

Eisener:: Two thousand two, maybe? Or 2003. The project you were coming in to talk to us about---we had to take a script from The Limey, a dialogue scene and we had to reshoot it in our own way. You came in and gave your thoughts on shooting dialogue. What have you been doing since then?

Dorfman: Gosh.

Eisener:: I think you showed us About a Boy.

Dorfman: Love That Boy.

Eisener:: Yeah, sorry.

Dorfman: Since then I did a documentary on girls who were labeled the slut of their class called Sluts. I've directed for television, comedy and drama, I've consistently worked out scriptwriting, feature films---I have four of them in development.

Eisener:: Wow.

Dorfman: And development's a bit of a hole to get into, because you never really know what's going to happen so I've always tried to do other things at the same time. I do a lot of shooting for other people. This weekend I was shooting a documentary for a woman from Toronto. It's something I want to keep up because I love shooting, I love to keep up with the technology. It lets you know as a director what your options are. And I'm still doing short films, I'm doing something with the NFB right now. What were you doing this weekend?

Eisener:: I think you did Sluts through Arcadia Entertainment? I was doing a little documentary show that's on a boat that's racing around the world. And one of their stops was in San Diego, so I went there. It's called Go Deep.

Dorfman: And what are you doing otherwise?

Eisener:: Right now I'm finishing a short film, a 15-minute film called Treevenge.

Dorfman: Is it the revenge of the trees?

Eisener:: Yeah it's the revenge of Christmas trees.

Dorfman: That's a great idea. I would like that movie, because I don't like Christmas, or Christmas trees.

Eisener:: Oh, this movie's for you. Other than that we're developing our Hobo with a Shotgun feature that we made a fake trailer for.

Andrea, can you talk a bit about how when you were a child, you were obsessed with horror?

Dorfman: When I was a kid, we weren't allowed to watch television. We had a TV in our house but the only thing we were allowed to watch was the news, which is actually kind of horrifying, but we were allowed to watch on Sundays and Saturdays. I think because we didn't have television I became obsessed with ghost stories, I became addicted to them. So when I started going to movies, I went to horror movies. I had a very strong imagination as a child and I became pathologically afraid that my parents would die because you start to become aware of the world as an eight- or nine-year-old and how terrifying it is. and I became obsessed with the news and newspapers and what was going on.

And that, I think, fueled my imagination for filmmaking and storytelling, but I also became really obsessed with musicals. I think now I lean toward the schmaltzy, sentimental type of storytelling. I work with a writing partner in Toronto and she's way more of a realist and she's a bit cynical. And I think we compliment each other because I'm a little more sentimental and I'd say she's a little bit more cutting and so we balance each other out.

I always thought I would make a horror movie, but I think I've exercised that part of my personality in a way and I don't really need to. Now I have no appetite for horror movies at all. I can feel a little part of me is addicted in a way, like I always wanna see the movies but then I'm completely freaked out and repelled by them. There's certain images I really can't have filed in my mind right now. and as filmmakers we're visual people, and I think we have to be careful about what we ingest as visual artists.

How did you get into film? Was it something you always knew you wanted to do?

Eisener:: In the beginning it was horror movies as well, it was similar for me. Though I was allowed to watch television, my Mom stressed that if I saw scary movies I would get scared and have nightmares and I didn't want that. Sometimes there would be trailers on TV for scary movies and those would scare the crap out of me. At the same time, because my Mom really didn't want me to see them, there was this thing of wanting to taste the forbidden fruit. There's something I couldn't do but I really wanted to---sometimes I would go to friends' houses and check out a horror movie.

But what got me into film probably was watching horror movies because it was the first genre I got into. I remember seeing Jaws for the first time and being scared, it affected me on a big level---I didn't want to go swimming in the ocean or even in a swimming pool. That affected me on a mental level. That started this downward spiral...maybe I wanted to get scared more?

When I was in grade 9 we had a project in my drama class and we had to make a play. Me and my best friend made a script for a play, and our drama teacher told us it was too crazy for the stage and I wouldn't be able to do it. But she said, 'Maybe you could make a movie.' And I thought OK, that sounds like a cool idea. So we grabbed a camera, went out and shot something and edited it on VCRs. We brought it back and showed it in front of the class. And seeing their reaction to something we'd created, reacting so positively about it, it was kind of addicting, seeing them react to what we'd made. And I wanted to do it again. I think the next week, got the camera out, shot another one, showed it to our friends, and that led, basically to what I'm doing now.

What were you doing in '93?

Dorfman: I was at NSCAD. It's interesting that '93 was the year that The Coast came out and that this is what we're reflecting upon. I came around to film again---as a kid I had, in those days, it was super-8. My dad had a whole bunch of super-8 movies when we were kids and then the film got too expensive and it was kind of a hobby and he wasn't into it anymore. When I was about 12, I dug out the camera and it was funny because I was always into photography and one of the things I'd gotten at some point was a Kodak camera that was Polaroid.

And then Polaroid sued Kodak because they were the only ones making Polaroid cameras, and they asked everybody to give their cameras back and they gave everybody at $50 gift certificate for Kodak. So I took the camera back and I bought super-8 film which at that point was probably seven dollars a roll or something. I had this whole stack of super-8 film. That's what I started making super-8 films with.

But it never occurred to me that---and this is where I think maybe the biggest difference was at that time---that you could actually make a living doing it, making films. Because we really didn't have it in school, I was doing it completely on my own---now there are so many media programs in school---and I was really into sort of what you were saying: I'd make something and then show it to people. It was really the combination of storytelling and technology and audience. There were these components that were really thrilling. And the magic of film, literally: you'd send it off and it was nothing in this little black plastic canister, and you'd get it back and hold it up and be like 'Oh my god, there's an image there!' So eventually I started showing these films.

But then I went to university, and I kept coming back to art. So I left university and went to NSCAD and immediately what I was drawn to was filmmaking. But there was no real filmmaking program at NSCAD, there was just the film co-op . So it would've been 1993, I started going to the co-op. I started making films through the one class they had at NSCAD, which was in conjunction with the co-op.

That was the year I made sort of my first short, an experimental documentary. I had been in Montreal when those women were killed, the December 6 women, the 14 women. And obviously like everybody else in the world it had a huge impact on me. And that year I made a film, it was a graffiti art film. I got friends of mine and we went under the bridges in the south end and we did these huge, larger-than-life images of 14 women under the bridge, and I filmed it.

Eisener:: Awesome.

Dorfman: That was probably the first film I did that I showed in front of a wide audience. And that would've been 1993. What were you doing in 1993? Were you born yet? I'm just kidding. You're older than 15 years old.

How long from starting to make shorts to Parsley Days?

Dorfman: I made Parsley Days in the summer of 1999. The thing you have to understand is, I've never had a plan. I never thought 'I want to make Hollywood films' or whatever the pinnacle of the career trajectory I seem to be on as a filmmaker is. If I've ever had a credo, it's that I want to make the films that are the most honest and have the most integrity for me. When I made Parsley Days, I really feel like I had no idea what was going to happen. It felt like a big experiment.

I spent a number of years as a camera assistant. Really to learn camera, I was quite interested in becoming a cinematographer at that time and then became more interested in being an actual storyteller. So I ended up making Parsley Days literally on a wing and a prayer, whatever that phrase is, cause I was collecting short ends of film; I had a great community of artists and filmmakers in the community so I just cobbled together a crew and somehow I managed to finish it on credit cards, and then it got into the Toronto film festival---it really just kind of took off.

And it was really incredible and thrilling and definitely enabled me to make my second feature, and through that I started working with my writing partner, but I've always been very open. I guess I just don't ever know what's gonna be next, and I feel like anything can happen at anytime. What about you? Do you see a certain trajectory?

Eisener:: I love film, and I'd love to keep making film, so that's my goal.

Dorfman: What I mean is, we can all make films. All you have to do is say 'I'm a filmmaker' and put it on YouTube and the next day have an audience. In some ways it's a really exciting time for filmmakers because there's nothing in our way. It's not like deciding I want to be a dental hygienist---you actually have to go to school and jump through some hoops and apply for the job. I mean, really, it's modern-day storytelling---it used to be cave people, telling stories around a fire in a cave, talking about the kill that day or whatever. When you say 'I wanna keep making films,' are you interested in all kinds of films, or documentary or short or specifically feature films?

Eisener:: My main focus is feature films. I am doing documentary work right now and it's great, I'd love to keep doing that too. But I guess I just want to continue to be able to keep telling stories and do what I need to make a living at it as well. I could get a job doing something else, but I'd love for my main focus just to be working on films and telling stories. That is my goal, to be able to do that. If I couldn't do it, if I couldn't be making a living doing it, I'd still do it. Before working at Arcadia I was working at a comic book shop, just making movies on my own time.

Dorfman: Do you make comic books too?

Eisener:: No. I'm not that great with drawing, but I'd love to write them.

Eisener:: Yeah, I had an opportunity to shoot a film on 16mm. And it was great. I loved it. Most of my movies are shot on video, started off editing with two VCRS, then moved up to iMovie and then Final Cut Pro. The way you can shoot with video, it doesn't really cost anything. So you can be lazy and just shoot as much as you want. There's some good things about that---I can be a bit looser, a little more creative, I can decide I want to do a different kind of shot and I can just throw it into that position.

I found with film it makes you more prepared, and you really had to plan out what you were going to do before shooting. I wish I had more of that. I find now that I struggle with being more prepared. With my last movie there were times when I thought I could just move the camera around wherever I wanted, but it was more of a film setting with a bigger crew, and I couldn't really do that. It threw me off.

This was also the first time I let someone else shoot a movie for me. Say if there was a conversation, you'd light everything up for this person, shoot them out, then turn camera and light this person and shoot them out. I used to just go back and forth and do whatever, but with a bigger crew I couldn't do that. It would be pretty bad if I shot everything out that way and then started shooting here and said 'Oh, I forgot to get this thing over here.' But with film I remember planning everything out so that I wasn't wasting film. I think the film I shot at school, there was one shot I didn't use. With video there's hours of stuff I'm not using sometimes.

Dorfman: I think there are some great things about video, but I think it makes you forget to think carefully about the choices you make. Really in a shoot day you only have so many hours. So with video it's not like you can shoot and shoot and shoot ad nauseum, because eventually you have to cut and move on from a scene. It's the same with editing---it's a nightmare editing with so much footage. When I made Parsley Days I didn't have much film, so sometimes I only did one take, and that was the take. I didn't have a choice. Even in Love That Boy---it was such a low-budget film that even though it was shot on video and blown up to film to 35---I still didn't shoot and shoot, I just didn't have the time.

Eisener:: Do you watch a lot of movies?

Dorfman: There are definitely some directors who I love, but I'm not a cinephile. I'm not the kind of person who watches a movie every day, and I can't rattle off a million different movies. I love film and I also love books and graphic novels and people telling stories, but I think it's all the same thing. It's all part of the same concept, which is a story and how we take it in as a reflection of our own experience as human beings.

I've seen pictures of your DVD collection. How big is it?

Eisener:: It's ridiculous, close to like 2,000 movies.

Dorfman: You should open a video store on the side. That could fund your next film.

Who influences you?

Eisener:: My friends are a big influence, my childhood. I think a lot of my style and the way I tell stories comes from my childhood and growing up.

Dorfman: From what? Something that happened in your childhood, or what movies you were watching?

Eisener:: How I acted with my friends, the things we did, our personalities. My films now are probably films I would've loved watching as a kid.

Dorfman: I think that's such a great philosophy. Those are the kind of films we should make: the kind of films we wanna see. Because that's sort of you saying your assets to the absolute maximum nth degree. It's mining yourself. There's only one Jason Eisener: out there. All you can be is the best Jason Eisener: or Andrea Dorfman you can be. You can't be anybody else.

What do you want your key job to be? Writing? Directing? Producing?

Eisener:: I've always shot and edited and directed most of the films I've worked on. I've been writing them with my best friend. His name's John Davies and he's been wanting to step in more as a writer and a producer. And so now we'll have story meetings, come up with a story, and he'll take it and write it and I'll direct it or shoot it. But now I've been wanting to give the camera up to someone else and learn how to direct a camera operator. Which was so hard at first. Always if I've had a shot in mind I would set it up and do it, putting the lights out and everything the way I wanted it, but now I'm trying to learn how to direct someone else to do it.

Dorfman: I definitely think I'm a writer-director. The times that I've read other people's scripts, as a director and tried visualize it---it's not that I can't do it, I can do it, it's just that I don't have that passion, that keep-you-up-at-night excitement. It feels very much like a job. Which is fine and I've learned tonnes of stuff to be able to do that. And in some ways that's how I've made a living; I've directed for other people. But if you talk about your baby or whatever---my passion projects are all writer-director. And some of these I'm co-writing.

Eisener:: I find it hard. I have it easy with my best friend---we grew up together, we've been friends since grade primary. We have the same tastes and think on the same level. I've directed other people's work too, and I don't mind it, but there are times when you are up at six in the morning and then you're home by 12 o'clock and then you stay up till four in the morning to prepare for the next day. And you're only running on two or three hours of sleep. Sometimes if you're not super-passionate, if it's not coming from you, it's hard to do that. But when it's your story and something you feel passionate about telling, you could run on nothing. No food or freezing cold weather or no sleep and you'll have that drive to do it.Dorfman: I think there are actually a lot of similarities between me and Jason. More than differences.

---Tara Thorne