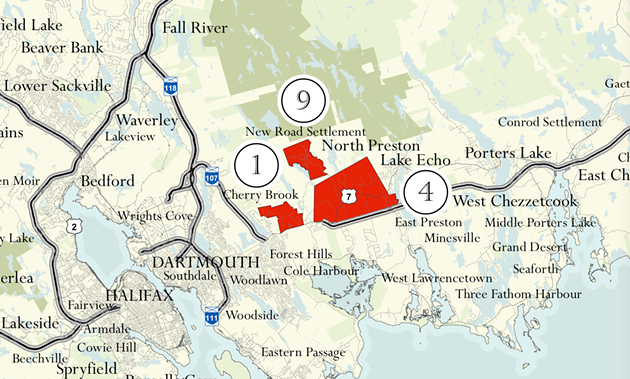

A decision came out of the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia recently. The Downey v. Nova Scotia ruling affirms what pro bono lawyers and the grassroots movement of North Preston residents (that spurred the mobilization of those pro bono lawyers) have been telling the Department of Lands and Forestry for at least half a decade: the way in which the department has been administering the Land Titles Clarification Act is wrong. This is incredibly frustrating, because the government has publicly promised to work to help clear up title for residents in North Preston and the other LTCA areas, while it privately sets up barriers that it had no authority in law to impose in order to reject applications.

If you’re wondering what the LTCA is, the following is a brief history as I understand it. If you were a loyalist who fought for the Crown in the late 1700s and were white, the government provided you with both land–100 or more fertile acres–and a deed to said land (which was taken from unceded Mi’kmaq territory, but that’s a whole other story). If you were a Black loyalist, the government may have provided you with land–not the fertile land offered to your white counterparts, but land nonetheless–however the government never bothered to provide you title to that land. (Additionally, if you were a Black loyalist, you likely fought for the British in exchange for your freedom from slavery.) The issue of receiving land without a deed was not only true for the loyalists, but for the other Black settlers who came to live in Nova Scotia. The government’s complete failure to follow through on its promise planted the seed for 250 years of continued systemic racism in our province.

About 200 years into this history, enter premier Robert Stanfield. Stanfield created the Interdepartmental Commission of Human Rights in the 1960s. "It will not be easy to find solutions to problems affecting certain segments of our population which have been more than 200 years in the making. But as great as these problems may be, their magnitude must not deter us from making a beginning," he said about the commission’s findings, on Human Rights Day, December 10, 1962.

"Progress will be slow and will depend very largely on the cooperation of all our citizens. We must remember that the social and economic problems of minority groups, who for one reason or another are not enabled to occupy their rightful place in the community, adversely affect us all."

Stemming from the commission, the LTCA was born as a simplified process to finally grant title to African Nova Scotians. But well-intentioned as the LTCA was, it did not go so far as ensuring the government provided clear title to all residents. Instead it relied on residents to apply for title. The process required applicants to hire a lawyer, largely because the department charged with reviewing applications was either categorically rejecting them or not moving them forward. Applicants also needed a lawyer to write the deed, and a surveyor to set out the metes and bounds of the land.

You might be thinking, Well, that makes sense. I had to hire a lawyer when I bought my house. There’s simply a cost to doing that. But that is not what is happening here. The government failed to provide title when it was obliged to do so.

The very same department embarked on a decade-long project to clear up titles on 28,000 properties in Cape Breton, in Richmond and Inverness Counties. That project wrapped up two years ago, and no one had to apply. The government went in and cleared it up because it had made an error in not providing clear title 100 years earlier. For North Preston and the other LTCA areas—13 places in total, including Cherry Brook, Little Lorraine and Drumhead—this is not something the government is willing to do.

Dwight Adams, from the North Preston Land Recovery Initiative, explained in an interview with CBC back in 2016 that it was his understanding that historically individual LTCA applicants “were always given quite a bit of a runaround” from the government. It is rumoured that the department had a number of applications that were ongoing and unilaterally closed the files without reason in the 1990s.

In 2017, after much pressure on the government and the formation of a group of pro bono lawyers to assist with files (thanks in large part to Angela Simmonds, a North Preston resident and lawyer), the government announced $2.7 million dollars worth of funding to try to address the issue of land titles and said that it was considering “amending legislation [the LTCA and possibly other legislation including the Probate Act] to reduce barriers”. In the Department of Natural Resources (the prior iteration to the Department of Lands and Forestry) 2017-18 work plan, a performance indicator was a “Percentage increase in number of properties in East Preston, North Preston and Cherry Brook for which the land title has been clarified.”

I have no idea how they planned to make that happen, since the department was–and still remains–entirely dependent on residents bringing forward applications and then having the stamina to endure the horrifically bureaucratic process, which, by all appearances, seems to have as its goal to deter applicants from applying and to close files as quickly as possible without approving them.

I worked as a pro bono lawyer on a very straightforward file. It took over three years to secure title for my clients from the department, and even when the minister finally provided the Certificate of Title, the department’s lawyers tried to claim a further title search was required at my clients’ expense. Nowhere in the LTCA is the minister entitled to ask for or require that. I am loathe to think about how unrepresented claimants are treated.

Recently, the department rejected an application because the applicant failed to prove that they have occupied the land for 20 years. This new purported 20-year “requirement” has no basis in law, and does the exact opposite of what the government expressed in its 2017 press release. Again, this was pointed out multiple times in consultation with the pro bono lawyers and various government departments since at least 2016. Instead of following the direction of those lawyers, the department began to apply that standard and put it up on its website that it was a requirement for applicants.

Worse still, the department then had to defend its position, which was a hardline insistence on the 20-year adverse possession standard, in court. The minister lost in court and now the application has to be sent back to be reconsidered by the department again. The decision of Justice Jamie Campbell should not have come as a surprise to minister Iain Rankin, particularly in light of the fact that I had sent him correspondence directly outlining this issue months ago and, as is mentioned throughout this piece, lawyers from the pro bono project had been advising against his department using the 20-year standard—on the basis that it is wrong in law—for nearly half a decade.

In a statement provided to CBC News last week, minister Rankin says, "We will continue to look for ways to streamline this process and remove barriers wherever possible.” For Rankin to say streamlining and removing barriers is something to “continue” suggests that this is work his department has actually been engaged in. Respectfully, that is baffling in the context in which this comment was made, which is as a direct result of his own department putting barriers up, which it had no authority in law to do.

I will follow up with Rankin with respect to his now-public commitment to again review his department’s process, but, quite frankly, it is exhausting.

I am always struck by the words of Fred MacKinnon, who sat on the Interdepartmental Committee on Human Rights from which this legislation was born. "I was struck by two very evident facts," he said about trying to move bureaucrats to do the right thing. "The first related to the long and laborious task of persuading public servants and politicians that change was essential and, if delayed, change would be thrust upon us and second, the leadership of the premier.”

The LTCA needs real leadership. Minister Rankin has an opportunity to champion it. I think often of the hours, days, months and years community advocates and then lawyers have lent their expertise to the minister and his predecessor and that department. Despite Rankin’s most recent verbal recommitment to revising the LTCA process, I remain deeply concerned about the applications before the Department of Lands and Forestry. I hope Rankin is up to the task.

Robyn Schleihauf is a lawyer in Halifax. She runs a solo practice assisting professional regulators, human rights commissions and ombudsman offices with complaint files. She is interested in professional ethics, equity, diversity and restorative justice. You can find her at robynschleihauflegalwriter.com.