It’s clear from the very first guitar strum that opens Legacy—the long-awaited debut LP from neo-soul superstar-in-the-making Aquakultre—that the table is set. The CBC Searchlight winner’s record asks upon entry that you taste its opulence. There are pomegranates strewn on the linen; deep bowls of cold-skinned grapes; flaky sea salt swimming atop combs of honey. A platter of horns carries you through the album while the soft crash of cymbals cleanse the palate. Make no mistake, not that there’s room for your ears to: This is a feast.

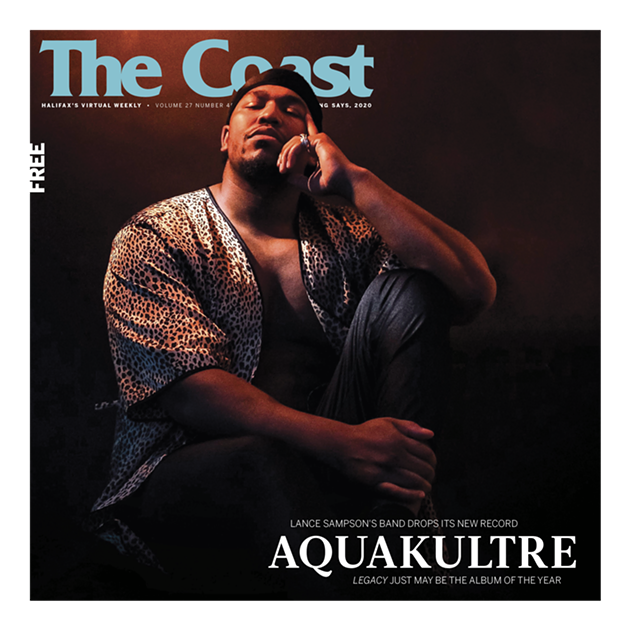

And no one’s arrived hungrier than the golden-throated voice behind it all, the band’s front person and driving force: Lance Sampson.

“Music shouldn’t be hard. It’s your creation, you just do it as you do,” Sampson says of his band’s 10-course meal for your ears, out tomorrow via Black Buffalo Records. Dive in and you’ll taste everything from the freewheeling futurism of Sun-Ra to the lyrical deftness of Common to the blues-stained soul of Sam Cooke. Sampson himself is the first to say Legacy’s roots grew out of his love of the likes of Erykah Badu and D’Angelo. “When you start making music with good frequencies it makes people feel good. Lyrics that are relatable: As long as I’m doing that, as long as I’m being true to me—that’s all I care about,” he adds.

It’s good you brought your appetite.

There’s a moment on Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band Live/1975-85, a five-LP odyssey that chronicles a decade’s worth of live performances by the blue-collar troubadour, where the song “Growin’ Up” fractures and fissures. As the band pauses, Springsteen is left giving a small monologue to the silent crowd. “My father always said: ‘You know, you should be a lawyer. Get a little something for yourself,’” he narrates. “Then my mother, she used to say ‘No, no, no, no. He should be an author. He should write books. That's a good life, you can get a little something for yourself.’ Well, what they didn't understand was that I wanted everything.”

The same feeling given by that crowd’s roar reaches out in the snapping drumbeat of Legacy's second track, “657.” Sampson gives Springsteen’s sentiment a 21st-century update, spitting the hook “657 to the four/I just wanna give more, I just wanna give more, I just wanna give you more”—harmonizing with the waterfall of bright piano rolling off his back.

He’s waited for his table. He wants the whole menu. And, Sampson gets just that with an offering that’s a veritable buffet of tastes—what collaborator Nick Dourado (who Sampson bills as a sort of “artistic director” of Aquakultre) describes as an album that ranges from “soaring, emo-pop songs and country ballads.” Fuelled with a tangible hunger for more noise, more feeling and more meaning, it all leaves the listener’s stomach grumbling with the sudden realization of how big a song or a voice can be.

“You wanna have a guess of what ‘657’ means?” Sampson asks with an audible smile, speaking by phone a week before Legacy’s release date. He entertains three guesses (A ticket number? An amount of money? A phone number fragment?) before explaining what’s behind his record’s first engine roar: “‘657’ is actually complete gibberish. It has no significant meaning. The reason why I named it ‘657’ is because if you know me real well, I just say the randomest shit all the time. We’ll be playing cards and I’ll say something crazy and you’re laughing but you don’t know why you’re laughing. But I just feel like naming the song ‘657’ goes to show how silly I am.”

Legacy was recorded in a breakneck seven days at Calgary’s National Music Centre, a place where Searchlight winners get sent to cut their next single. It’s also a place where many of Elton John’s pianos and the synthesizer TONTO—of Stevie Wonder fame—sit atop quiet altars.

“Most people who get that residency usually leave with one pro song, to three—or just a bunch of demos. And we finished a whole album,” says Dourado, the piano, horns and co-backing vocals in Aquakultre (and accomplished musician in their own right, performing in Century Egg, Budi and Beverly Glenn-Coupland’s band). “From the minute we got there—and even before we got there—we were just so focused. It’s not an opportunity we usually get…In terms of creative residency kind of thing, we were just so prepared. And, there’s no computerized sound on the record at all. So we pretty much went and made Lance—whose message we all think is really important—a 1970s Marvin Gaye record.”

But don’t let the speed at which recording poured forth fool you into thinking a single part of the album wasn’t simmered and sure. As Dourado puts it, Sampson is “so fearless when it comes to music and writing and trusting his own ideas and stuff.” To them, Sampson’s knowledge of songs borders on innate: “If he sings something, whatever the blues is, or whatever regular song form is, it’s usually somewhere present in it. He’s just so intuitive.” They later circle back to this, adding: “Because I don’t even think that Lance necessarily thinks he’s that good or that he’s even convinced by it. He just doesn't have to doubt the meaning of his words. And we don’t have to doubt if the songs are worthy—there’s just nothing to think about. It’s like, yeah, we want everyone to hear what Lance has to say to his beat.”

It’s as if each track stewed inside Sampson’s bones before tumbling forth. And, after all, aren’t a stir-fry and a braise both fully cooked?

Sampson came to music late. “I used to listen to hardcore street rap: I’m talking AR-Ab. If anyone’s not familiar, AR-Ab is one of the hardest people to come out of Philly. All that hardcore street rap and all that stuff that was really toxic,” he says. “I have a love-to-hate thing for trap music. You can’t deny the feeling it gives you. But the thing I hate is the crazy shit they be talking.”

He learned guitar and began penning his first songs in prison (though he had been rapping since age 15), refining his talent between stints at Burnside’s Central Nova Scotia Correctional Facility and the Springhill Institution. A little before that, when Sampson was 16, Chicago rap legend Common’s seminal album Like Water For Chocolate blew the doors off Sampson’s ideas what music could be.

“Once I started opening up my palate to listening to different music and how it made me feel, it started opening my eyes,” Sampson says. “Listening to different music is what started changing my personality, changing my patience for things.”

Over the next few years he became voracious, listening to album after album by everyone from Jeremy Dutcher to Leon Bridges to vintage soul singers (“that 1960s, old G’s whip car music like The Sinceres,” he adds).

The need to devour spread to books, too: “When I went to prison and started seeing the dudes I really looked up to in the streets, guys that were like the ultimate hard-asses, that were feared, that I was trying to emulate? Once I saw them in person and realized OK, they’re reading books? What? OK wait a minute, they’re playing instruments? They’re reading about Indigenous culture? They’re actual scholars,” Sampson remembers. “The OGs I used to look up to, they’re just trying to figure out who they are.”

He would go on to finish writing the song “Sure”—yes, the one that snagged him the 2018 CBC Searchlight competition, one of the country’s biggest opportunities for unsigned artists—while winding down his time at Springhill Institution.

By March 2017, he’d drop the five-track EP Water Temple, which, as Sampson told The Coast that same year, was named “from a Zelda game I know and love, and for me it also means the versatility I manifested with this project, because I used to rap and I thought that’s all I knew.”

The songs shuddered with the same audible emotion of neo-soul legend D’Angelo’s breakthrough record Brown Sugar. Romance? Sex? A Groove so deep you could swim in it? Sampson brought it all on his debut, a solo iteration of Aquakultre that saw his singing and rapping backed by either his own acoustic guitar or beats he built himself.

“We”—begins Dourado, meaning themselves and fellow now-members of Aquakultre Nathan Doucet and Jeremy Costello—“were sort of fortunate because we were some of the first people that saw Lance perform when he was in Halifax. We saw one of his first shows, just by chance, and he’s a very powerful performer. The very first time I saw Lance sing I was like wow, that’s crazy. I bet he could sing over a drum kit—most people don’t project like that.”

“Lance’s family is from Africville,” they continue. “There’s an entire city of people who were dislocated from the place that they lived and had ancestry for hundreds of years, and the street that their project is put on, is the same street as the only venue where the concerts happen. And yet, for the first decade I was in Halifax, I never saw anybody from the square play The Seahorse. Literally never—and I went all the time. It’s sort of unrelated but that’s kinda how we all came in touch with Lance, too: When Lance showed up and was so ready to perform and represent where he’s from, there was no question that we were gonna try and find him as many platforms as we could of the highest calibre for him to be like ‘yo, this is what’s up’.”

And so, they did—first by asking Sampson to play as part of a 12-piece band at the 2017 indie music event Sappy Festival. (“When everyone was just together enjoying that same moment at the same time, it made me high as heck. And I’m like, I’m chasing this,” recalls Sampson of that early August performance, his first with a band.)

After that test drive, it was on to the recording studio, where Legacy captured the proverbial lightning in a bottle in a live-from-the-floor tape.

Sampson’s emotive delivery and measured message (he wants you to know yourself the same way Lizzo wants you to love yourself), paired with the kaleidoscope of Dourado, Doucet and Costello’s musical prowess, became the powder keg for a record so explosive it demands to be heard—to be understood. The best part of all, though, is that it also makes you dance while you do so.

“Jeremy is like an operatic singer drone musician; I’m primarily a free jazz musician and Nathan is like a punk, hardcore drummer,” Dourado explains of the group’s twisted sonic lineage. “And we’re all coming together to make just whatever it is that Lance hears.”

The perfect case study of this is track four, “Wife Tonight.” Originally released by Sampson in 2017 as a make-out jam for the Soundcloud generation, Dourado and co. reworked the song into something unrecognizable: A funk-infused tune that now sounds like a lost Stevie Wonder track.

The song is a favourite of Dourado’s: “‘Wife Tonight’ is awesome because there was a Hohner Clavinet, which is the exact keyboard Stevie Wonder uses. He used it to record ‘Superstition’ and I was like whoa, icon!—and that’s what ‘Wife Tonight’ is recorded on,” the musician adds.

“Can you imagine what it’s like for people in this industry to wrap their heads around Lance?” says Dourado, who calls Sampson one of the most positive people he knows. “We got to CBC at eight in the morning when Lance won the Searchlight and had to do the Q interview. And the minute we walk into the CBC building, Lance is walking the halls singing Shania Twain’s ‘Up!’ at the top of his lungs. You can hear him through the entire building. He jokes around with every single person we meet. It would take me hours to recount the amount of times I saw Lance do things like that where you’re like this is like a movie, this is unreal.”

In the same way that Outkast carved a spot on the music landscape between party jam and social commentary, the lyrics of an Aquakultre track will melt across your mind with the intensity of a sour candy: You pucker. You’re surprised. You reach for more, instantly and instinctively.

While Dourado’s horn section on the album’s lead single “I Doubt It” (recorded live in a marathon session before their time at the NMC ran out) is what hooks into your eardrum first, Sampson’s lyrics prove, within the same second, to be on an equally high level: “Wait a minute/Capitalism and prison systems, I can’t tell the difference/Meanwhile, I’m too busy bigging up my people, encouraging them to speak loud,” he thunders in a tone that’d awe Andre 3000.

Yes, the musical range is its own buffet. Of course, you’ll be going for seconds.

If we’re wondering what legacy Legacy could act as a sequel to—which appetizers this feast follows—a fair bet to entertain would be Gil Scott-Heron’s Pieces of a Man. Sampson, after all, proves the revolution was meant to be a crooned, not televised. This is the sort of thing that’ll nourish you, even as you gorge on it.

Says Dourado: “Kind of what the whole Aquakultre project is about for me, in a particular way, is being how can we get people to focus on what this person is saying? Because the message about family and treating other people with respect is so worth talking about in the world that we live in today.”

Lick the honey from your fingertips. Wipe the running juice from your chin. Then, fill your plate again. “I always come back to a line by Common,” begins Sampson, referencing the lyric “Affecting lives is where the wealth and the merit is,” from “Nag Champa (Afrodisiac For The World),” but perhaps doing it one better: “He says: ‘Inspiring the life of the youth: that’s where the merit is.’ That’s what I do it for: As long as I’m touching people and helping them change their life in any kind of way for the better, that’s what I’m here for.”