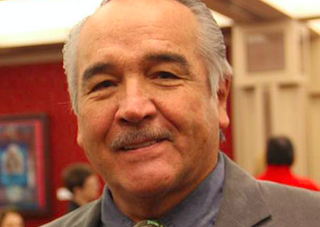

National chief Dwight Dorey of the Ottawa-based Congress of Aboriginal Peoples has been meeting with indigenous men and women across the country, holding consultations regarding the Supreme Court of Canada’s anticipated ruling on whether aboriginals who live off-reserve are Indians under the Constitution Act and therefore entitled to the rights that fall under federal jurisdiction. The top court’s decision will affect about 400,000 non-status natives and approximately 200,000 Metis.

Dorey, of Cole Harbour, is a 68-year-old Mi’kmaw man and a former president of the Native Council of Nova Scotia. He was with the late Metis leader Harry Daniels when the Saskatchewan native filed the initial court challenge in 1999. While holding consultations in the Maritimes, Dorey spoke with The Coast about the upcoming legal decision.

This case has taken about 17 years to decide—were you preparing for a long legal battle from the get-go?

Not as long as it has actually taken. Partly because we didn’t really expect the Crown to go all out in trying to have the case thrown out—have it dragged out—and that’s really been the case with it. And so, this has gone on a bit longer than what we originally expected.

How many off-reserve indigenous people live in Nova Scotia, and how would their lives change should the Supreme Court rule in their favour?

In Nova Scotia, the numbers are about equal in terms of on-reserve and off-reserve. [Perhaps 14,000 live off-reserve.] The case is going to have a significant impact on off-reserve, mainly non-status and Metis people right across the country.

What prompted Mr. Daniels to launch this case back in ’99?

It was mainly because [the forerunner of] the Congress, which had been in business since the early ’70s, would all through the years regularly deal with the non-status and Metis issues and the jurisdictional question always came up. The federal government would basically take a position that if you’re not status Indians living on the reserve, then you fall within provincial jurisdiction. The provinces would, however, say if you claim to be of indian ancestry—non-status or Metis—then you are a federal responsibility. So we described ourselves as “the forgotten people,” and there were growing problems with health and other related quality-of-life issues we felt needed to be dealt with.

If the Supreme Court decides for the Metis and non-status indians, what would have to happen in the near future—negotiations between Ottawa and the indigenous parties?

That would be sort of the next step. The federal Court of Appeal actually ruled on non-status and Metis people. What it didn’t rule in favour of, and we wanted the declaration, was that the federal government has a fiduciary duty to all aboriginal people—and that non-status natives and Metis have the right to be consulted and negotiated with. So basically, that’s what was appealed to the Supreme Court.

And should they emerge victorious, any idea what this would mean to the Canadian taxpayer, in terms of federal dollars earmarked for the affected aboriginal groups?

It’s going to be a significant cost to the federal government, in our view. However, if we win the case it doesn’t mean (Ottawa) has to do anything. Technically, I guess that’s right. But it would be incumbent on myself, and the leadership of the Metis and non-status people, to pressure the government to do something.

Interview conducted and edited by Michael Lightstone