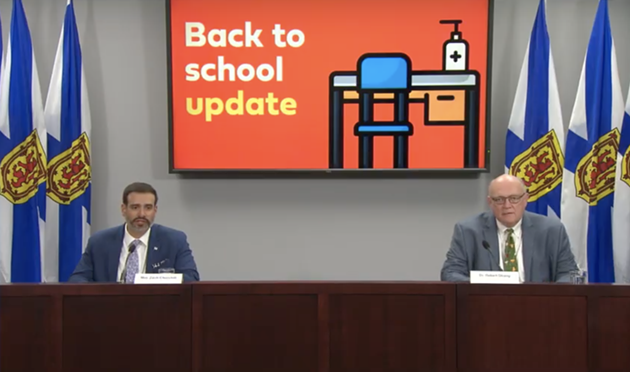

Since the plan was first announced on August 14, concerns from the public have ranged from ventilation in classrooms to class size to the stress of finding extra days off (after all, if your child gets COVID-19, you'll likely have to stay home during their 14-day isolation period).

“There certainly continues to be a lot of discussion, even some concern, even some criticism, about what will happen in schools if COVID-19 does occur,” said Strang.

To help alleviate those concerns, Strang said he was giving additional information about what would happen when a case was discovered in a school.

“I fully expect we'll get cases of COVID-19 in schools,” he said. “It doesn’t mean that the plan has failed. It doesn’t mean that there’s a crisis. It simply means that what we have expected to happen has happened, and then we will respond appropriately.”

First, the suspected case would be isolated and tested. Once a case was confirmed, Strang says there are several questions that public health would ask to determine next steps.

“Ultimately, the detailed actions will be dictated by the circumstances at any given school,” he explained.

This includes asking questions like: Is the individual a staff or a student? Is it a single case or multiple? What type of exposure or risk to others has occurred? Where did the case likely get infected? When would they have been contagious? Where were they and what did they do while they were contagious?

“How did they get to school, was it on a school bus? Did they participate in a before or after school program?” Strang says. “That’s the type of questions we use to get detailed information.”

In terms of contact tracing, Strang said there are three levels of contact: close contact or high risk, medium risk and low risk. For now, both medium and high risk exposures would be sent home for 14 days to self-isolate, even if their subsequent tests return negative results.

“For students in cohorted groups in elementary and junior high this is likely to include all students and staff within that classroom cohort,” said Strang. “For higher grades, the students in non-cohorted groups, this may include all the students in the classes the case attended.”

Low risk exposures–for example, students who walked past each other in a hallway–would continue to go to school as usual.

“They’ve only had brief contact with a confirmed case. So this would be anyone for instance who’s only in incidental contact,” said Strang.

Strang said the goal was to refrain from closing schools entirely and instead send home cohorts or classes or students who need to self-isolate.

“I certainly hope we won't have to close a school, but we need to be realistic and we're certainly prepared to do that,” he said.

However, also on Wednesday, the Nova Scotia Teachers Union (NSTU) released a statement saying that the return to classrooms would cause “chaos.”

“Without smaller class sizes and proper physical distancing schools won’t adhere to public health guidelines in place for other workplaces,” says a statement from NSTU president Paul Wozney. “By also exposing students to the disorder that presently exists in most schools it could also negatively impact their ability to learn under new and unproven conditions.”

The union is advocating that the government tacks on PD days for staff at the beginning of the upcoming year, to allow them more time to prepare for students. Otherwise, the NSTU is threatening to file a policy grievance for “breach of the province’s duty to ensure a safe learning and teaching environments for students and teachers.”

But the back to school plan itself is still not set in stone. Strang told the public that many of the regulations were made to be adjusted once we see how exposures play out in the real world.

“As we get more experience with this, we may be able to say that we don’t be as cautious with moderate risks,” he said. “We’ll see what experience we get, but our preference is always to err on the side of caution.”

But the top doctor seemed certain that at some point during the 2020-21 school year, at least a few outbreaks will occur, somewhere in the province.

“Anybody in a school environment could be in a position where they have to be at home self-isolating for 14 days,” he says. “So, teachers and parents and students should now be thinking about having a plan in the possibility that they need to be at home for 14 days, and how that’s going to be managed at home.”