As the food bank manager for the past five years, Davies-Cole is a wealth of knowledge, spouting off facts about the history of the organization between answering questions from carefully-masked volunteers who come to the door of their office to borrow a stapler, turn in a lost student card and ask questions about specific foods (the food bank also offers vegan, halal and gluten-free options).

“When I started, the school never even acknowledged that they had a food bank,” says Davies-Cole. “And I think a lot of it was not wanting parents to think, ‘Oh like my kids are there starving?’ Me, I think it’s more that they didn’t want to answer the hard question, ‘Why are my kids starving and you’re upping their tuition?’”

The DSU Food Bank is one of five food banks on university campuses in the province, but it’s the only one that’s also open to non-students. (All of them are mostly stocked by Feed Nova Scotia, the charity supported by The Coast’s Halifax Burger Week.) From its location in the Dal SUB basement, the food bank gives out between 100 and 160 boxes a week, with up to 14 days of food each.

“We didn’t shut down. During Covid, when everything got shut down, we moved to the hallway and people came up to the double glass doors and they would request through the door like what they wanted,” says Davies-Cole, who is also a full-time student.

A few weeks later came the switch to ordering ahead online. With a plexiglass pick-up window, pre-made boxes and reduced operating hours (Mondays and Thursdays compared to its regular six days a week), the food bank has adapted to Covid while increasing awareness in the community.

Davies-Cole says they want to unpack the privileged North American way of thinking about food, because most people are food insecure in some way, at some time, “but they don’t think they are.”

In September, over 10,000 students arriving in Nova Scotia from outside the Atlantic bubble were required to self-isolate for two weeks and get tested for COVID-19 three times. But no one regulated how students were accessing food during isolation and beyond—in the “new normal.”

Dalhousie’s quarantined students were “required to order their meals from local food outlets” while in quarantine. Self-isolated students at King’s got meal hall food delivered to their rooms. SMU made meal plans mandatory this year “to ensure all students have access to guaranteed meals/food service should they have to self-isolate at any point during their stay at residence”—at a hefty price tag of at least $1,845.

With these new food-access regulations baked into university policies, food security is taking up valuable space in students’ minds.

Food insecurity is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as “the state of being without reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food.” But in reality, it’s much more complex.

“There's other elements that I think come into play around access to food that might be particular to students, and that aren’t linked to finances,” says Lesley Frank, a sociology researcher and associate professor at Acadia University. “Things like lack of transportation or lack of time to do the food work necessary to feed yourself.”

Frank says there’s a range of food insecurity, from marginal to moderate to severe. “It's severe when you have to go without. When you have to limit the quantity of food that you consume,” she says. “It's moderate when you have to modify the quality of food you consume, and then marginal when you worry about running out of food. Cutting down the size of your food, getting food items that are cheaper, less nutritious.”

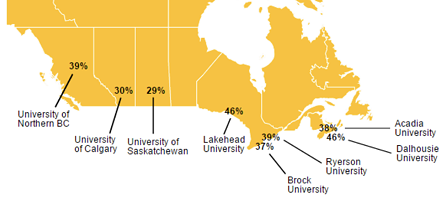

Similar studies at the University of Saskatchewan and Dalhousie University have shown university students consistently report food insecurity rates about three times higher than the national average of 10 or 11 percent.

Frank says the reasons behind this could vary widely: “The challenges will be unique. It'll be unique based on where are people living? Are they living on campus, are they living off-campus? Are they international students? Are they Nova Scotia students? Are they in our bubble, are they outside the Atlantic bubble?”

P

overty comes to mind first for many when thinking about a lack of nutritious meals.

“This is a misconception, that food insecurity is only around low-income communities and low-income students, but it actually isn’t. By having a survey that’s only looking at financial accessibility, you might not be seeing the larger picture which is where I think students fall into the cracks,” says Cassie Hayward, who wrote her 2019 political science thesis on food insecurity among Nova Scotian students.

The Canadian government’s survey–called the Household Food Security Module–does exactly that, asking 18 questions (10 for adults and eight for children) about financial food insecurity.

“The adult ones are basically like, ‘Have you ever stressed about not being able to afford food? Have you ever missed a meal? Have you ever missed more than one meal over the course of three months? And stuff like that,” says Hayward.

Hayward, who grew up in Dartmouth, says an empty bank account isn’t the only reason people go hungry. “You’re missing out on the three other pillars of food insecurity when you’re doing it like that.”

Those pillars include physical availability—the idea that in your country you have the actual availability to get food, food utilization—the idea that you actually have the space to cook food safely, and food stability—this idea that throughout your entire year you’re able to access food.

Hayward is particularly concerned about students’ food stability because of the rigorous academic year. In her research, she asked students if the same 18 questions would have different responses during periods of academic stress.

“During stressful academic periods of time, specifically midterm and exam periods, it went up to 74 percent of students,” she says, despite less than 10 percent of those students self-identifying as low-income.

Other results from Hayward’s study are shocking, and not in a good way: 65 percent of students found fruits and vegetables unaffordable, while more than half had problems finding time to get groceries.

“Sixty-four percent identified with struggling to make food and 54 percent identified as having problems for groceries previous to the pandemic. I can only imagine things will get worse,” says Hayward.

However, studies like Hayward’s and Frank’s are few and far between. “The Canadian Government looks at statistics for various different demographics, but students are not included in that, and then even on an institutional basis the majority of universities aren’t looking at it,” says Hayward. “The few studies that we do have are typically done by outside researchers or sometimes by NGOs, so it’s a huge data gap in food security.”

With the added stress of a pandemic, Frank also worries that students will have less time and money for food than usual. “Student loans come in late, they might be lower than expected, students might have gotten less work hours than they expected during the summer,” she says.

Students often get a bad rap for having money and time to spend hanging out with their friends sipping beers and eating pizza, but that’s often not the case.

“They have this assumption that young people at university, they all seem like they have money. They socialize a lot, they go out and appear to have money. And it's very judgmental because they'll say, Oh, isn't this something that is just a rite of passage that everyone's supposed to experience when they're a student? Or 'we were all poor,'” says Frank. “And I'm like, well no–not everybody was, not everybody is now.”

For many students, getting to the grocery store is harder because of Covid, and students who take transit could face long trips, long lines and reduced store hours. Like everyone, they’re shopping less often.

“If you can only go to the grocery store once a week, if you go less that means you have to have more money to get what you need to get you through that time,” Frank says.

For the fall term, many meal halls will have reduced hours to allow for increased cleaning, meaning students who work part or full-time jobs, students with children or who care for loved ones, and generally anyone with a busy life has a hard time finding time to eat.

Students from outside the Atlantic bubble know what it’s like to isolate for two weeks. In the coming months, anyone who has potentially been exposed to a case will be required to do the same.

Hayward recommends keeping pre-made kits in your dorm or apartment. Granola bars, snacks and foods that don’t require a lot of cooking (but are still healthy) are good in an emergency. “And if we go into lockdown,” Hayward says, “just reach out to friends, reach out to the community.”

For those who don’t have friends to deliver homemade meals, groceries or take-out, self-isolation could lead to a lack of nutritious meals. Attempting to get ahead of this, Acadia set up a system to deliver groceries to students in isolation, “Because not everybody has a friend,” says Frank.

“It takes an open dialogue to make sure we're not forgetting anybody that's going to fall through any cracks,” says Frank. “COVID has, of course, highlighted all the cracks in our social safety net. It's an age where we all more than ever can recognize how vulnerable those living just around the poverty line are.”

Off-campus, other avenues like food banks have seen increased traffic this year. Feed Nova Scotia says between March 15 and May 1, it distributed 30 percent more food than the same time the previous year.

At the DSU Food Bank, Davies-Cole is seeing the same thing. The first day it was open after the lockdown in March, the crowd at the food bank drew attention.

“Our lineup went around the building back onto South Street, cause they had to line up along Seymour. And of course, there was police out patrolling cause everything’s locked down,” he says.

After a quick call to the police to explain, the volunteers got back to work.

“We had to let security know to contact the police and say, we’re a food bank, and food banks were exempt, essential,” Davies-Cole says. “We went from no one knowing us to becoming front-line workers.”