As Halifax gets ready for Hopscotch, visiting artist Aaron Li-Hill disagrees with HRM councillor Linda Mosher that graffiti has no place at the annual hip-hop showcase.

"I find it funny she's saying that," says Li-Hill. "What's being painted at the festival is not illegal. Even if it's in that style."

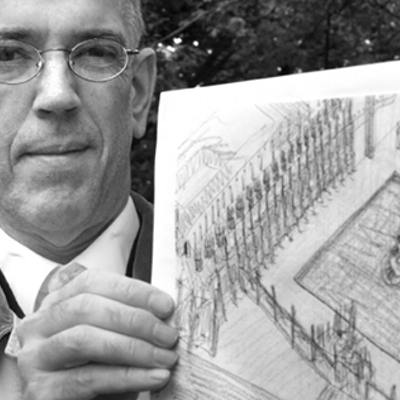

Toronto-based Li-Hill, one of three "urban artists" showcased at Hopscotch this year, has travelled the world painting and is no stranger to graffiti controversy. "It's one of the hard things about graffiti," he says, "it's very misunderstood."

Mosher, who heads HRM's graffiti task force, felt last year's use of "bubble letters" at Hopscotch was too similar to tagging, which she considers "out-and-out vandalism." "Nobody is going to try and propose someone's moniker as art," she says.

Li-Hill disagrees. "As a graffiti artist, you kind of have to go through those stages," he says. "When I was a kid, I painted in those alleyways, because that's where you start."

Likewise, tagging and graffiti are as much about appreciating the performance as the aesthetic, explains Li-Hill. "Anyone can make art in perfect conditions. But to be out on a street corner at 4am---out of this crazy amount of physical and mental pressure, they're creating something beautiful." The tag, he argues, is "the remnant of something that happened between the person and the street at that moment."

Fellow artist Christian Toth disagrees. "I do not in any way condone tagging," he says. "There is no graffiti at the festival. There is no tagging at the festival," adding anyone who thinks so is "completely uneducated."

Raised partly in Halifax, Toth had "a lot of fun" working with Hopscotch last year, but like Mosher, he wants to disassociate the festival's agenda from graffiti. "Whenever you mention graffiti," he says, "people tend to paint that with a negative brush."

Li-Hill, meanwhile, finds graffiti's mostly illegal nature to be refreshing. "I find graffiti an interesting secondary option in the art world," he says. "You're able to have your stuff seen, but it doesn't belong to anyone. The average person doesn't go to museums, or art galleries."

That independence is what made graffiti integral to hip-hop, but Mosher remains unconvinced. "If you watch the videos, they're all smoking drugs," she says. "So we don't promote everything related to hip-hop."

The city spends millions annually on removing graffiti, she says, and has recently started a three-month pilot project with the specialists at Goodbye Graffiti. The company, which already has a $100,000 tender from HRM for paint removal, will receive $47,000 to patrol the downtown core, identifying and removing any graffiti in a three-day window.

Li-Hill feels such actions aren't beneficial. "Graffiti is literally putting colour back on walls," he says. "Urban society, we cover everything with muted greys and muted browns. The natural world is a lot more colourful. Even if it seems intrusive, I think there's still a basic benefit in that. It's showing that somebody was there."

Li-Hill also believes festivals lelp put a "friendly face" on graffiti and open a dialogue between artist and citizen.

Mosher is unlikely to be part of that dialogue---she's no longer planning to attend Hopscotch after numerous "cranky" phone calls. "I don't want youth to think I'm trying to take away artistic expression," she says. "But at the same time we have a vandalism problem."