How far have we really come concerning race relations and equity in Nova Scotia since the desegregation policies of the ’50s and the civil rights movement of the ’60s? So close, but yet so far, sums it up.

We have made many inroads as people of African descent in regard to building capacity and infrastructure in our province, and yet we continue to be dramatically underrepresented in mainstream occupations and positions.

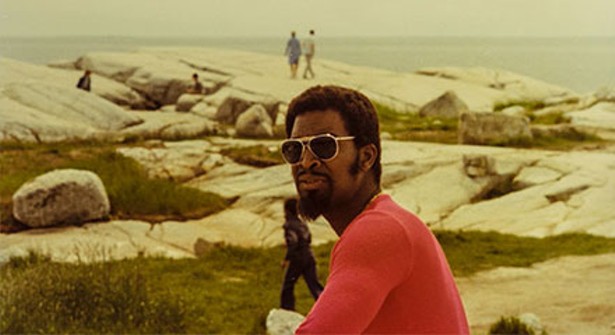

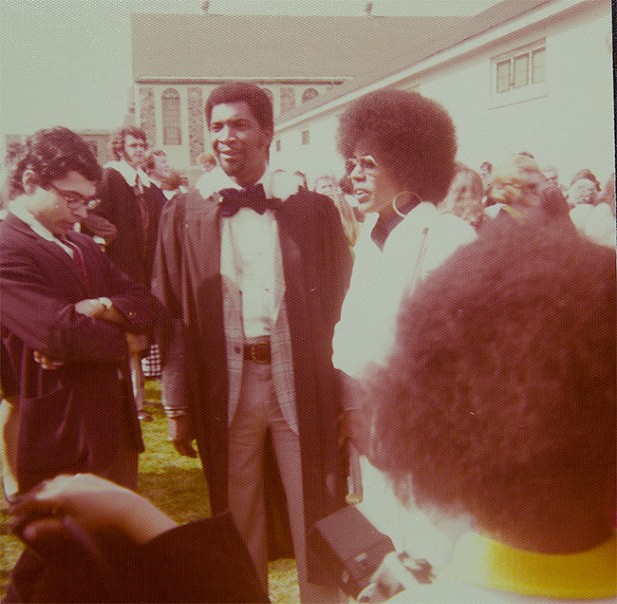

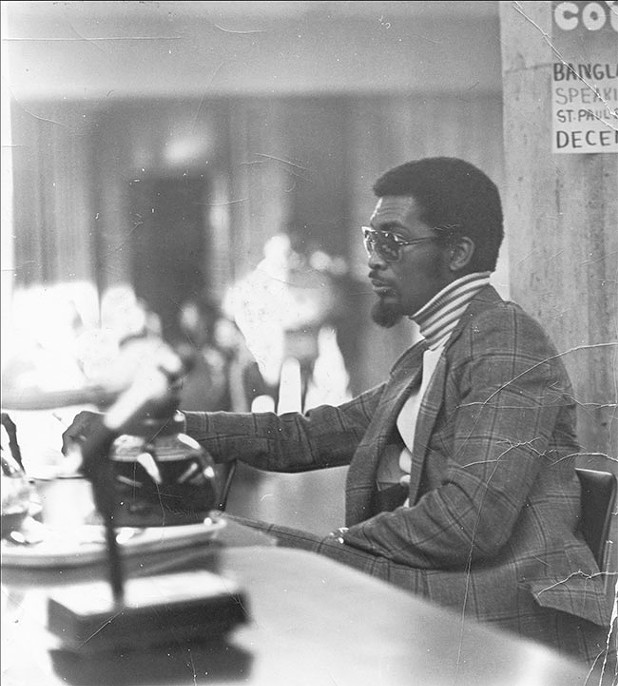

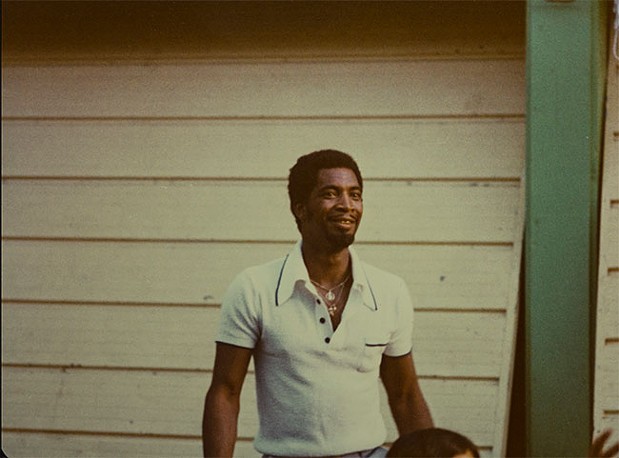

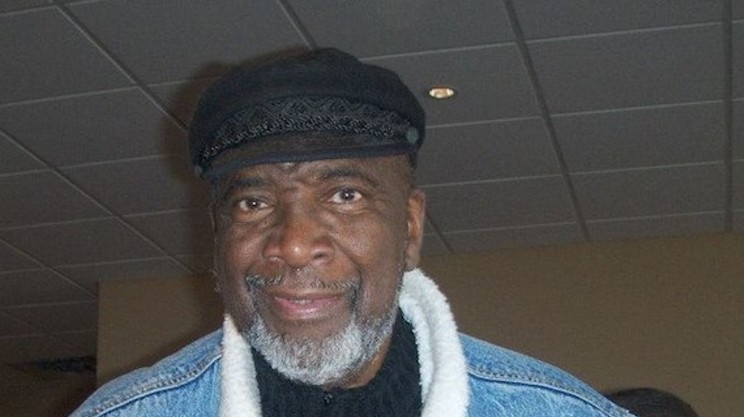

The late Burnley “Rocky” Jones and his former wife Joan Jones were trailblazers who, alongside many others, risked life and limb to put us in this place—a place that claims equity for all, but much of the time feels like “equity limbo.”

Both were key players in the civil rights movement of the ’60s and were integral in shaping programming and organizations for Blacks in this province. Their hard work carved paths and blazed trails to make it easier for African Nova Scotians to stand up and be heard after more than two centuries in this province.

There is a long and rich history of people of African descent in Nova Scotia. We first arrived in 1605 and began migrating as Black Loyalists in the 1700s, Jamaican Maroons and later as refugees after the War of 1812. Blacks settled in communities on the peripheries of villages, towns and cities. Over the years, about 50 tight-knit Black communities formed and survived on the outskirts—many without amenities such as grocery stores, schools, medical and other essential services afforded to most white communities.

During my parents’ and grandparents’ era, segregation was at its peak. Even churches were segregated, giving rise to the African United Baptist Association. The church and the work it did was more than a place of salvation. It was a life preserver, protecting the culture of a unique group of people.

Not so long ago, Blacks were permitted in white

Today people of African descent continue to live on the fringes of society. Segregation continues in our workplaces,

Black professionals often spend most of their time in the company of white colleagues due to the lack of diverse workspaces. This is also true for leisure time spent in mainstream music venues, dining establishments, bars, academic events and work functions.

Rarely is this

Rocky and Joan were all about agency. The couple believed in taking control and ownership of one’s own business. In a largely white province, Black folks

The Jones’ were about self-empowerment—about building capacity and infrastructure in our community. They were a vital part of the development and implementation of organizations and structures that remain in place today. The Transition Year Program and the Indigenous Black and Mi’kmaq Law program at Dalhousie University were both created due in part to efforts made by Rocky Jones. Both programs aided in the advancement of those who would otherwise not have been able to gain access to such educational programs.

The Black United Front and the Nova Scotia Project were created to foster the advancement of people of African descent in Nova Scotia in the areas of economics, education, housing and employment. The Jones’ likewise had a hand in developing both.

Other groups are a direct result of their

In the early ’60s, Rocky and Joan met prominent Black Panthers member, Stokely Carmichael and his wife Mariam at a writers conference in Montreal. They became fast friends, and Stokely and Mariam were invited to spend some time in Halifax. This became

The philosophical platform that Rocky stood on was similar to that of Stokely Carmichael’s, hence the natural partnership between the two. At the forefront of the civil rights movement during the ’60s was Martin Luther King Jr. with his message of civil disobedience. The Black Panther party did not share this philosophy. They believed that you fight power with power. Rocky was a champion of empowering people to stand up for what they were owed and to fight for what was rightfully theirs by virtue of being born free in a democratic society. His intent was never to incite aggression nor violence, but to defend one’s self and most importantly one’s family and community.

Joan was a champion of the cause by being a deputy of the movement. She was the backbone of the operation. She held the pieces together and kept things moving. Rocky and Joan’s home became the headquarters of the movement and their kitchen table was where ideas were born and implemented.

Their home, its door always open, became a space where all were welcomed. It eventually became too small to accommodate those interested in becoming involved in the movement. Kwacha House, established in 1967, became the successor of the Jones’ house as a place where ideas were birthed and developed. The vast majority of its attendees were Black, but

Rocky was a strong voice during this period and spoke out unapologetically about the rights and privileges that African Nova Scotians were not being afforded.

But if you speak out against or challenge the status quo, especially within an institution, you get labelled as a troublemaker, as intimidating and worst of all, you get ostracized.

Those institutions forget that the “troublemakers” speak out not just for themselves, but on behalf of their mothers and fathers, their grandparents and all those ancestors whose voices were silenced.

When those employers ask a Black worker to “tone it down,” they do so without insight into our history and those who came before.

Respectful of others’ feelings. Direct, but diplomatic. Honest and forgiving. Our words are confident. We will never be silenced by a hierarchal system of oppression.

Challenging practices, even respectfully stating an opinion, with the voice of social justice and advocacy in mind is never easy. The fear in doing this is that your words will be categorized as “insubordination.” A very troubling word, suggestive of a notable imbalance in power.

Recently, former Planned Parenthood Federation of America president Cecile Richards said in an interview that, “Whatever you’re doing, if you’re not scaring yourself, you need to be doing more.”

How many times did the fears of speaking out run through the minds of civil rights activists like Sojourner Truth, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., Viola Desmond, Rocky Jones and Joan Jones?

There is no question Rocky suffered as a result of being the voice of the cause. It became increasingly difficult for him to gain employment over the years. His name became synonymous with radicalism and he was overlooked for many employment opportunities for which he was more than qualified.

While standing up for his own civil rights and the rights of others, Rocky became a threat to the white establishment. During their campaign, their family was threatened by two attempts to set their home on fire.

Rocky and Joan eventually overcame these hardships by creating their own employment opportunity with a business specializing in leather work. Joan’s resourcefulness kept their growing household of five children afloat and they continued to open their home to all needing a safe space—including a number of foster children.

Rocky and Joan were committed and instrumental in the movement to create change and improve conditions for Blacks in the province. They worked diligently and tirelessly throughout the years, yet despite all their accomplishments the system of policies and policymakers in Nova Scotia—policymakers that so infrequently resembles any racially visible person—continues to leave us exhausted.

Our current reality is that we are still celebrating firsts in a province where we have been a part of the landscape since the 1700s.

So many of the incidences that have recently occurred in the United States have left us in Nova Scotia appalled. While we publicly display our disgust toward these type of basic human rights violations, do we own up to our own displays of blatant ignorance and racism here in Nova Scotia?

Do we continue to turn a blind eye or downplay such atrocities as the countless number of young Black men that do not make it to their 21st birthdays?

Do we continue to give audience to a certain loud-mouth schmuck city councillor and his racist rants?

Do we continue to allow patients to visit our emergency department, the largest trauma centre east of Montreal, with an extremely slim chance of being treated by a Black nurse, paramedic, technician or emergency physician working in this expansive emergency room?

When will all of this no longer be OK?

It’s a struggle to come up with the language to explain how this discrimination feels—how invalidating is this society that says everything is equitable and fair.

Carefully we censor what we say to not intimidate or make others feel uncomfortable even while addressing grave injustice.

There’s still so much further to go, but they have propelled us forward.

Rocky and Joan Jones’ due diligence and heavy sacrifices forged a community of resilient people who continue their fight into the 21st century. For this, we are forever in debt to Rocky and Joan.

Wendie Poitras is an educator, community advocate and visual artist. Recently she wrote and did some research on a documentary, Rocky & Joan, by Olesya Shyvikova which will be released next February.