Former Halifax councillor Harry McInroy was arguably one of the worst councillors in the history of HRM---his repeated meeting absences became something of a running joke, and when he did bother to appear, he was ill-prepared and mumbled inane comments. His Cole Harbour constituency no doubt sighed in relief when McInroy, who opted not to run for re-election, was replaced by the capable Lorelei Nicoll in the October 18, 2008 municipal election.

But no matter. Just 10 days later, at its October 28 meeting, council decided to appoint McInroy to the Halifax Water Commission. Did no other candidates, with better work habits, apply for the position, or was this simply a courtesy appointment for a former colleague without concern for the best interests of the water commission? We don't know: discussion of McInroy's appointment was held in secret.

Like all of council's appointments to boards and commissions, the secrecy surrounding McInroy's appointment was justified as a "personnel" matter, meant to protect the privacy of the applicants.

That justification is nonsense. Privacy protection is rightly accorded civil servants who are hired to implement policy decisions made by others. But the policy makers themselves---the members of boards and commissions---should not be given privacy protection; the public has not just the right, but the duty, to scrutinize those making policy decisions. Such public scrutiny is the very essence of democracy.

In fact, most other city councils in Canada and the US make such appointments in public meetings, as did the former cities of Dartmouth and Halifax. "People applied, and we discussed them, let the chips fall where they may," explains former Dartmouth mayor Gloria McCluskey, who now sits on the HRM council.

In any event, McInroy evidently wasn't much interested in the job, and sometime over the next few months---just as the water commission needed all the help it could muster to deal with the sewage plant disaster---he left the commission.

McInroy's appointment was just one of 71 issues discussed in 30 secret, or "in camera," council meetings in 2008. I've analyzed each of those issues, and have assessed whether they were an appropriate use of secrecy. (The complete analysis---including spreadsheet---is at thecoast.ca/bites.) I found that 23 of the discussions (33 percent) were improperly secret. Another 21 discussions (30 percent) were partially improper. Just 26 of the secret discussions (37 percent) were held properly.

As with McInroy's appointment, many of the discussions were held in secret simply to hide potential contentious political decisions. For example, an applicant to the Police Commission was rejected, likely because he advocated for a civilian review board to investigate allegations of police misconduct.

Council has the right to make the political decision not to have a civilian review board, but such decisions should be made in public, not behind closed doors.

Council is often simply reflexively secret, holding secret meetings for absurd or meaningless reasons, as evidenced by secret discussions of a disagreement with the federal government over "in lieu" payments for Citadel Hill National Park, or by a letter council wrote to the Utility and Review Board over regulation of energy efficiency programs. In both cases, the secrecy served no purpose at all, as all the information was immediately available from federal and provincial sources, respectively. (It will come as no surprise that council wants the feds to pay more money for Citadel Hill, and an effective energy efficiency program.)

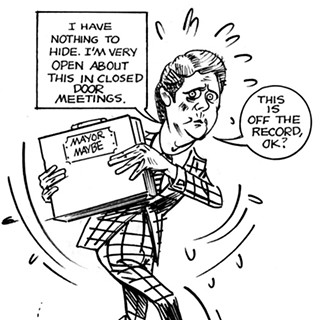

Deciding to hold in camera council discussions and withhold information from the public should be an extraordinary event, an action that should cause everyone pause and deep consideration. And yet, there is no written policy guiding how council holds secret meetings or what information should or should not be released to the public.

In practice, public disclosure is spotty and inconsistent. Usually, a staff report guides council's secret discussion, and in many instances those reports are supposed to become part of the public record at a later date. Last week I asked for 14 such reports related to secret meetings in 2008.As of Wednesday morning, I've received one.

In a democracy, the presumption should be that information should be public unless there's good reason for it not to be, but in Halifax the presumption is the opposite.Halifax council demonstrates its contempt for the public 63 percent of the time it meets in secret.