Affordable housing is one of those terms that seems to mean less every time you use it. At least, that’s how Elaine Williams sees it. “When they say ‘affordable housing,’ that drives me crazy.”

Williams has lived in Mulgrave Park, at the northern end of the Halifax peninsula, for decades—45 years, to be exact, minus one year she spent in an apartment outside the community. (“I didn’t like it.”)

Although Williams could afford to live in another part of the municipality, she’s chosen to stay in the public housing complex at Mulgrave Park. It’s her home, after all, and her mother, her grandchildren and one of her grown sons live here, with another son on the waiting list to move in. She’s spent over a decade volunteering to help the community. She’s helped set up a food bank, build new playgrounds and put together the Caring and Learning Centre—all resources she says have proven essential, especially for those on income assistance.

“They know in between payments that their kids are always going to get something to eat.”

Between subsidized rent and the support the community offers, Williams says that residents of Mulgrave Park can just about get by. But head up the hill—or even just over the retaining wall that separates Mulgrave Park from the rest of the north end—and it’s a different story.

In October of 2015, the Housing and Homelessness partnership—a collaboration between non-profit organizations, the private sector and all three levels of government—reported that over a quarter of households in HRM are spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing (30 percent being the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s threshold to determine housing affordability).

Twelve percent of the municipality’s population is in extreme housing need. That’s 46,000 people who are spending 50 percent or more of their income on housing. But non-market housing—including co-ops, rent supplements and public housing like Mulgrave Park—makes up only four percent of available living space in the city.

That means many single parents, new immigrants, refugees, persons with disabilities, seniors and young families are left without a lot of options. Williams has watched many residents try to leave Mulgrave Park, only to come back a year or two later.

“People have tried to move out,” she says, “but they can’t afford it.”

Inside Mulgrave Park’s Caring and Learning Centre, the large picture windows face onto the community and the harbour beyond. The blue-and-white edifice of the Irving Shipyard looms large in the bottom half of that view—one of the projects on which Halifax has pinned its ambitions for growth, including a hoped-for population increase of 50,000 more residents by 2021.

Farther south down Gottingen, condo and apartment buildings, albeit only partially occupied, are more proof for Williams that the neighbourhood she grew up in is changing.

These changes are exerting pressure on the city’s affordable housing. It’s a time bomb waiting to go off that will affect everything from the health of citizens and communities to the economic well-being of the city itself, but there’s a noticeable lack of vision on the part of those responsible for doing anything about it. In fact, try to figure out what the strategy is for addressing the issues with affordable housing—or even what those issues are—and the picture becomes very muddy indeed.

———

The consequences of all this are more complicated than someone not having a roof over their head. For Kelly Eagles, it was a question of family. Eagles spent the night before she called the Metro Regional Housing Authority sleeping under some low bushes near the dockyard. Her two children were staying with family while she moved between friends’ couches, camping out when the weather cooperated.

The MRHA—which funds and oversees socialized housing in the municipality— told Eagles at her first appointment that it would likely be a year before she could get into housing.

In the meantime, Eagles, 23 at the time, would be separated from her two children. “That was my biggest priority,” she says, “getting the kids home and back into a routine.”

She ended up getting a three-bedroom townhouse in Uniacke Square after only six months. Six months of moving from couch to couch. Six months of sleeping outside. Six months without her and her kids under one roof. “Nobody really seemed concerned about that, which shocked me.”

Canada is the only industrialized country without a housing strategy. Compare that to Austria, where in the capital city Vienna, the government controls 46 percent of the city’s housing stock and owns much of the land—a remnant of Austria’s socialist past. That means Vienna can and does facilitate the ongoing construction of affordable housing. And because of the ubiquity of high-quality public housing, private landlords also have to keep their prices low in order to remain competitive.

Canada, by contrast, doesn’t have a long history of addressing this issue. Yet, there are few subjects that permeate the national conversation more than real estate. For the most part, rising housing costs in Vancouver and Toronto dominate this discourse, while the rest of us look on with the mixture of empathy and Schadenfreude that characterizes life at the periphery.

Halifax homes come with a cheaper price tag, but the city hasn’t escaped its own brand of housing crisis. When this indistinct spectre is given a name, it’s usually “gentrification.” Rising property values have pushed housing costs ever higher, year after year. That’s particularly true in neighbourhoods like the north end, where average rent increased by over four percent in 2015—from $967 to $1,013 for a two-bedroom—compared to an increase of 1.7 percent for the HRM as a whole.

If anyone’s held responsible for this, it’s usually the municipality—after all, HRM benefits from rising property values through taxes. But trace Halifax’s housing crisis to its foundation, and you’ll find problems more complicated than gentrification at work.

———

Most of the Halifax residents mired in this housing crisis are renters. Although renters make up only 37 percent of the population, they’re nearly three times as likely as homeowners to be in some kind of financial housing difficulty, especially if that difficulty is extreme.

Halifax also has a higher percentage of residents in extreme housing difficulty than any other municipality of a similar size other than Victoria. As is usually the case, the cost of this housing crunch falls on those least able to afford it.

“Ironically when I came to Halifax I was going to volunteer at an organization like Hope Cottage,” says Jason Ivany. “Now I might actually have to utilize that service.”

Ivany moved from Bridgewater to Halifax last fall, intent on pursuing a degree in IT from the Nova Scotia Community College. But it wasn’t long before things started to fall apart.

First, Ivany was only approved for 20 percent of the student loan he asked for and had to drop out of school. Then a flurry of job applications—over 100, he says—were met with silence. In March, Ivany found himself facing eviction from his $725-a-month Spryfield apartment over unpaid rent.

When he went to the MRHA office to apply for public housing, he was told the wait could be anywhere from six months to five years. In the short term, he was given numbers for homeless shelters.

Ivany’s now waiting on his first income assistance payment. A single person on income assistance can receive a maximum of $535 for housing a month—although that number can be as low as $300—in a market where average market rent for a one-bedroom is almost $900. Non-market housing would offer Ivany the chance to pay rent that better reflects his actual income.

There are about a half dozen terms that will come up in this conversation about affordable housing (see glossary sidebar). Public housing is one form of non-market housing, but it’s not the only option on a spectrum that also includes shelters, co-ops and subsidized apartments. At the core, all these housing models are about finding a home for those struggling to live in this city.

For Ivany, that will take awhile. As of February, there were 1,273 people on the waiting list for public housing in the HRM. This includes people who are already in public housing and hoping to move to a different building. Wait times can fluctuate depending on need and the applicant’s preferred location.

“The municipality does have a role and can be thinking more strategically. Without assuming all the responsibility and without having things downloaded on to us, we can do things to make affordable housing a reality.”

tweet this

—Jennifer Watts, HRM councillor for Halifax Peninsula North

Meanwhile, no new public housing has been constructed in Halifax since 1993 (not including a number of provincial rent supplements, which subsidize private apartments so that they’re no more than 30 percent of a tenant’s income). According to affordable-housing advocates, the lack of development is only half the problem.

“We’ve been only adding a little bit at a time,” says Grant Wanzel, an emeritus professor of architecture at Dalhousie University and former non-profit housing developer in Halifax.

“Not only that, but while we were adding little bits at a time, the rest of it was deteriorating.”

The most recent notable example of this deterioration has been the sale of several properties belonging to the non-profit affordable housing provider Harbour City Homes. Nine buildings, containing 34 units, went up for sale by the affordable housing provider last August.

Harbour City had paid off its mortgage to the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation, which meant the province would no longer subsidize the organization. The indirect subsidization offered through provincial rent supplements wasn’t enough to keep rents low and keep the property in good condition at the same time, says general manager Bob Thompson.

“It wasn’t enough money to cover all the costs, operating and capital,” he says.

Then in December, another north end non-profit housing provider—Brunswick Street Housing—raised rents by hundreds of dollars after its funding agreement with the province expired.

Even the province is struggling with the upkeep of its public housing stock. Kelly Eagles says that just weeks after moving into Uniacke Square, she started noticing mice in her unit. Within months, she was catching two or three a day. As winter approached, that number edged up into the double digits.

But the biggest problem by far was the mold. It exacerbated her existing lung condition, making breathing difficult. With few affordable options available, she faced staying in an apartment that was literally making her sick.

After a year and a half of trying to get the issues addressed, she gave up and did most of the repairs herself with what supplies she could afford.

Nova Scotia spends roughly $60 million annually on affordable housing, although in 2015, about $6 million of the total budgeted amount for affordable housing went unspent.

An additional $42 million in accumulated federal funding will go towards maintaining Nova Scotia’s affordable housing over the next decade, $8 million of which was spent on repairs and upgrades in 2014-15.

“It all comes down to money,” says Bob Thompson. “If the money’s not there and the properties are falling apart...then the whole of social housing is going to collapse.”

———

The silent partner in all this is the Halifax Regional Municipality—silent because the city hasn’t been responsible for housing since 1996 when it handed that file over to the province.

At the moment, the HRM’s jurisdiction over affordable housing is limited mostly to zoning bylaws and property tax exemptions for low-income homeowners and non-profit housing providers.

But the winds of change are blowing at city hall. Jennifer Watts, outgoing councillor for District 8, says over the course of her two terms at council, the city’s outlook has shifted from apathetic to active, with an increased recognition that the city might play a part.

“The municipality does have a role and can be thinking more strategically,” she says. “Without assuming all the responsibility and without having things downloaded on to us, we can do things to make affordable housing a reality.”

The HRM’s Centre Plan is attempting to do just that. Community consultations recently launched and will continue for the next nine months for HRM’s somewhat starry-eyed solution to basically everything that’s wrong with the city’s current approach to development.

On a concrete level, it’s a strategy for how the HRM can facilitate a denser city. But dense doesn’t always make for a good city. Some research suggests the gains of denser living, such as a decreased reliance on cars, are small when measured against the fact that as land becomes scarce in cities, real estate prices and land assessments rise accordingly.

Discussing land assessments might seem like an activity that’s only marginally more interesting than, say, preparing your own personal tax assessment, or maybe just full-on death, but stay with us because this is important.

In 2005, the provincial government introduced a capped assessment program, which limited the amount by which property tax for Nova Scotian homeowners could rise annually. At the time of its creation, the province said that the cap would prevent families and seniors from being forced out of their homes. That seems an inarguably good thing, right?

In reality, the situation is more complicated. The cap only applies to people who owned their homes at the time the cap was imposed. If that home is sold to someone outside the family, the assessment shoots up. Apartment buildings—where many low-income Nova Scotians live—are also exempt from the cap.

Rising land assessment values can push people out of their neighbourhoods; yet blocking the rise of these assessments isn’t a straightforward solution either. Canadian municipalities are dependent on property taxes to pay the bills, and in 2015, Halifax’s chief financial officer pointed out that increases in expenses for services like waste collection were outpacing the rate set by the cap. That means the financial burden for those services was in some cases being shifted onto people less able to afford it.

Unintended complications like those are exactly the kind of thing the Centre Plan is ideally trying to avoid. And you, dear reader—as someone who doubtless has a deep and abiding interest in municipal zoning—will be delighted to learn that exploring those complications means delving into the finer points of land-use bylaws. Take a breath.

———

Let’s talk about density bonusing. It allows developers flexibility on zoning requirements in exchange for doing something that benefits the public. This could include affordable housing, although it’s only one option on a long list that developers can choose from.

Since the power to use density bonusing was incorporated into Halifax’s charter in 2008, there have been high-profile success stories—like the outdoor space around the Central Library. But in the eight years of massive urban development that density bonusing has been around for, it has thus far proved to be a flimsy tool in the construction of affordable housing.

In fact, only one downtown development project—the Mary-Ann building on Queen Street—proposed including affordable housing. But because the city didn’t have any way to administer that housing (remember, HRM gave up control over that mandate in 1996) the developer opted for another kind of benefit—public parking.

Even a better strategy on density bonusing would unlikely be effective on its own. It requires too many tall buildings to be built. So instead the city is focusing on inclusionary zoning, which makes affordable units a precondition for all development over a certain height.

The HRM doesn’t have a set understanding of “affordability,” though. So that definition—and a way to administer it—would have to be negotiated case-by-case with developers. That’s a problem. Just try and pin down “affordable,” and you’re already running into a roadblock.

“I think if you ask 10 people what affordable housing is, you’re going to get six different answers, or at least three or four,” says Ross Cantwell.

Back in 2004, Cantwell was commissioned by HRM to conduct a study on affordable housing. He’s now a non-profit developer and founding member of the Housing Trust of Nova Scotia.

Cantwell defines affordability not in terms of the lowest end of the income spectrum, but by what he calls the working poor—the single mother working full-time as a cashier, for example.

In other words: People making too much to qualify for income assistance, but not enough to afford market rent.

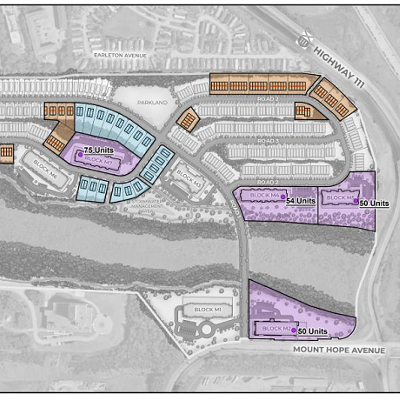

The Housing Trust has a number of projects aimed at affordable housing that are working their way through the civic process. Several of those properties are on Gottingen Street, but just to add to the confusion we’re going to use another one of Cantwell’s non-affordable housing developments to illustrate a point.

In this case, it’s the recently purchased vacant lot across the street for the Halifax North Memorial Public Library on Gottingen, which Cantwell and his partners bought for $3 million last year to build some “modest” above-market apartments.

Let’s pretend, for the sake of that $3 million price tag, that development was instead going to be affordable units only. What would be the math to make such a project financially viable?

Pick an arbitrary number and say there are 120 identical units in the building. That makes the cost of land $25,000 per unit. Incidentally, that’s the same amount as the capital funding incentive the provincial government provides to developers per rental unit of affordable housing.

So far, so good, right?

That $25,000 per affordable unit is the same for any size living space, regardless of whether it’s a one-bedroom basement apartment in Yarmouth or a two-bedroom in a downtown Halifax high-rise. Meaning that when it comes to building affordable units in higher-priced Halifax, the subsidy is less enticing.

Once the land is paid for, you’ve got HRM bylaws to contend with. One such bylaw requires new buildings constructed on the peninsula to have one parking space per unit. In the city, that probably means putting the parking underground, which Cantwell says can cost as much as $22,000 per stall.

Every additional cost in development is eventually passed on to the tenant, eroding the viability of affordable units from a developer’s perspective, says Cantwell: “There’s so many problems with this funding model I don’t even know where to begin.”

The province’s subsidy, by the way, only guarantees 15 years of affordable rent. If the landlord chooses to raise rents to market rates in year 16, there’s nothing to stop them from doing so.

Jennifer Watts says that even if the city can’t do anything about rising rents, it can try to make everything a low-income tenant does outside their home more affordable.

This includes encouraging development in communities where there are amenities like functional public transit. And in this respect, Halifax has a lot of work to do: Between 2008 and 2014, roughly 1,000 rental units were built on the peninsula, compared to over 4,000 in the Timberlea-Fairview-Clayton Park-Spryfield area. Transit in some of those communities is so unreliable that one Timberlea man complained to the CBC it was costing him work.

Yet, one of the ironies that seems to characterize affordable housing policy is that the very things that make a community holistically affordable—good transit, access to green space, libraries, a diversity of shops and services—also make it more desirable to everyone else. In turn, that leads to higher rents and less affordability. Round and round we go.

Addressing all of this will take considerable structural change across different levels of government, including possibly reversing some of the decisions made two decades ago and restoring some of the authority for housing to the municipality.

Even if all the regulatory minutiae was sorted out today, though, it would take a while to come into effect. Much of the apartment construction that will happen over the next decade has already been approved, and is therefore not subject to any affordable housing zoning requirements currently being hashed out.

———

There’s a fundamental question at the heart of this debate that Elaine Williams has been asking for a long time. “When they say affordable housing,” she says, “affordable for who?”

“Affordable” units can be less-than-market rent and still be out of reach for someone making at or near minimum wage. Even if they were within reach, tack on the cost of everything else—groceries, utilities, child care, debt—and that rent quickly becomes unsustainable.

Many of the affordable housing incentives that are planned for Halifax also depend on private developers. This might be expeditious from a development perspective, says Jim Silver, but it isn’t a good way to get housing constructed for the most vulnerable.

“Housing is quite expensive, so governments have to make a conscious choice that they’re going to invest in decent quality affordable housing for low-income people.”

Silver is an academic at the University of Winnipeg. He’s written on public housing communities across the country, including Uniacke Square.

Affordable just means below market rate, he says, and developers—like Ross Cantwell—might be receptive to providing affordable housing, but are unlikely to provide public housing (for which rent is usually based on a tenant’s income). It just isn’t profitable enough.

It might seem like the era of public housing has passed in Canada, but Silver says Manitoba is making strides. Since 2009, it’s constructed 300 units of public housing a year. Existing housing projects have been provided with community resources that have dramatically lowered vacancy rates, reduced crime and improved the health of the community.

“Governments can do that if they choose to do that,” he says.

Williams supports the province investing in the development of more public housing.

“Don’t do it like this,” she cautions, gesturing to the layout of Mulgrave Park. “To me we’re in a big box. The one thing that I found that they did wrong about public housing is not integrating them into the streets that were already in our city.”

In the meantime, Williams says a little communication can go a long way. Mulgrave Park—like all public housing developments in Halifax—faces maintenance issues.

The Metropolitan Regional Housing Authority has been doing what it can to keep the community’s 290 units in a good state of repairs, Williams says, but in the absence of more provincial funding the repairs go undone and animosity builds. It feels like the neglect is intentional.

The lack of maintenance eventually proved untenable for Kelly Eagles. Her health was at its lowest point two years ago. She says she suffered a paralyzing asthma attack, and her doctor diagnosed her with chronic pneumonia (which is mainly caused by mold).

Her partner begged her to move out, but after four years in Uniacke Square, she didn’t want to leave.

“It actually felt like what a community should be,” she says.

Eventually they relocated to subsidized military housing off Windsor Street. Eagles keeps in touch with a few of her former neighbours, and says that despite some improvements in recent years, many of them are still experiencing the same maintenance issues she did.

People are reluctant to complain, though. They worry major renovations would require them to leave, and they’re not sure they could afford whatever alternative is out there. Better the devil you know, and all that.

The buildings may be falling apart, but having that housing for the city’s low-income residents provides an unmatched safety net of support—allowing people to live in and be part of a city rather than being consigned to its outskirts. Now, that system’s threatening to collapse in on itself.

An increased role for the municipality, as well as the $2.3 billion in funding announced in the recent federal budget, could inject some stability into an issue that’s been teetering on the brink of collapse for years.

Money alone isn’t enough, though. Resolving this problem will depend on all three levels of government listening to each other, not to mention to those actually living with the realities of affordable housing—or lack thereof.

As it stands, perhaps the only thing that everyone can agree on is that there’s a problem. But it’ll take more than acknowledging the issue to build a foundation for affordable shelter that’s not just a house of cards.

———

Moira Donovan is a freelance writer in Halifax.