When Judge Gregory Lenehan acquitted taxi driver Bassam Al-Rawi of sexual assault charges in a Halifax courtroom last week, Jackie Stevens’ phone started ringing off the hook.

“Every time a high profile case like this happens,” says Stevens, executive director

Stevens says right now there’s a spike in requests from people reaching out for the first time. Some of them, she says, are in need of urgent care, “...people who identify that they’re in crisis, including people saying that they’re suicidal.”

Stevens is standing behind a low stage in the middle of Grand Parade, amid a sustained din of drums and voices, where she’s just addressed hundreds of demonstrators, holding signs and chanting, on a brisk, grey afternoon. It’s one of two protests against Lenehan’s ruling planned for this week.

As the monitors, cables and signs were being set up for the protest outside City Hall, two big developments were taking place. The Crown, under the Public Prosecution Service of Nova Scotia, formally launched an appeal to Lenehan’s ruling, just six days into its 30-day limit, citing numerous concerns of judicial error. Meanwhile, the McNeil government was announcing its own plans to increase funding for sexual assault service providers, like Avalon, pending federal funding.

In the 48 hours following Lenehan’s verdict, along with public outrage, came a flurry of commentary from sources who are usually mum in these cases. First, a press release sent directly to members of the media, by the Nova Scotia Criminal Defence Lawyers Association, on behalf of its 100 or so members. The letter defends not only Judge Lenehan’s ruling, but his character, calling him “fair.” The statement closes with this sentiment: “He is the type of person that any reasonable, informed member of the public should want as a Judge.”

Then came Al-Rawi’s defence attorney’s response to the criticism against the ruling. In it, he goes beyond saying his client was simply found not guilty. “He is an innocent man,” Luke A. Craggs writes, “..like all of us, he wishes to live in a safe and peaceful community.”

Many lawyers across Canada are watching these developments closely. One of them is University of Ottawa professor and lawyer Elizabeth Sheehy, a prominent national voice in cases involving sexual assault and consent in the law.

“Surprising, and disappointing” is how Sheehy describes her reaction to Lenehan’s ruling. She was one of many voices among lawyers and public officials calling for an appeal.

Sheehy says part of the problem, is the lack of clarity right now across lines in the justice system when it comes to the boundaries surrounding ability and inability to consent to sexual activity, which is at the centre of the Al-Rawi case.

“We don’t have a shared legal, social, political, or medical understanding of incapacity to consent,” and further, she urges, “We need to develop one.”

But Sheehy warns this isn’t an isolated incident.

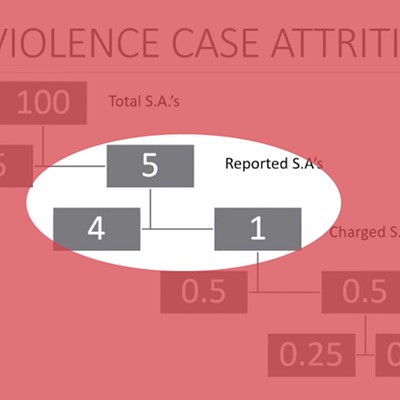

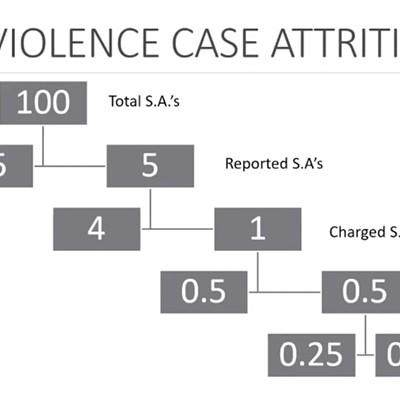

“This is an extreme case,” she admits, “but there are hundreds like it.”

Stevens couldn’t agree more.

“They’re not alone. It isn’t just individual [judges],” she explains, “We have a larger problem. We have systemic failure. And that’s what needs to change.”

As Stevens and her staff try to respond to the influx of requests for support, she says they’re being pushed beyond capacity as they also receive calls from survivors dealing with long-term trauma “resulting from childhood sexual abuse, or historical sexual assault.”

On top of that, there’s an increased demand for educational outreach appearances and, of course, media interviews. All of which, Stevens says, help to expand public discourse, and ultimately, understanding.

But, she says, this leaves the already under-resourced Avalon in a bind, unable to respond to the needs of its clients. A stress that affects both the people on the wait lists, and the staff, regretfully turning them away.

Looking more broadly, Stevens aims to publicly address issues in the legal system, and

“If the laws are stronger, and if there is adequate professional training for all legal and law enforcement to clearly understand [consent]…that will change some of this.”

Meanwhile, Sheehy remains optimistic that the intensity of public discourse and engagement will ultimately lead to change in the judiciary over time, explaining with both hope and regret in her voice; “Maybe judges could and will develop a more rigorous and nuanced understanding of capacity to consent.”

Stevens and Sheehy both support the federal Conservative party motion to require all rulings in sexual assault cases to be written, as opposed to Lenehan’s decision, which was made orally, in court, and only shared publicly because a reporter (Haley Ryan at Metro) published it.

Stevens says if regulations like these are adopted, “Regardless of who’s on the bench, that’ll ensure that this doesn’t continue to happen.”