Ask anyone and they’ll tell you it’s the way of the future.

Mayor Mike Savage tells the newspapers “it’s the way the world is moving.” Deputy mayor Waye Mason says in a radio interview that Halifax can’t call itself a high-tech city without it.

A recent survey from Corporate Research Associates found over two-thirds of Haligonians want ride-sharing companies on our roads.

“The question is why are such services not currently available to the public in a supposedly free market environment,” writes CRA chair Don Mills.

Right now, and up until October 11, HRM residents can take part in a simple online survey the municipality has put together to gather feedback on the taxi and limousine industry.

One question stands out: “Would you use an Uber or Lyft app?”

Uber is not outlawed in Halifax. There is nothing stopping the gigantic Silicon Valley company from setting up shop here and operating under the same rules as every other cab company; employing drivers with taxi licenses and acting as

But obeying the rules is not Uber’s business model. Our laws will need to change instead, it seems.

There is a palpable lust in Halifax to amend our taxi regulations to favour a massive foreign corporation that will abuse labour practices, shift money out of our economy and

The fight is packaged as a backwards government holding down innovation through red tape, to the benefit of greedy taxi cab cartels. Let

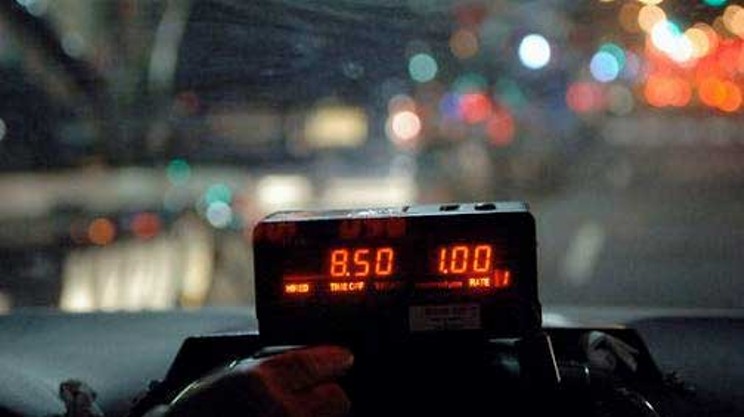

Nobody doubts that Halifax’s taxi industry needs improvement. The waits are too long. The cars are too few. But why do we think Uber is the answer? Well, because anyone can drive an Uber car. Because Uber is convenient. It’s cheap. It’s inevitable.

“Yes, but all that is

Here’s how it’s supposed to work: If a new company enters a market successfully with lower prices with better efficiency, then in a strictly capitalistic sense, it’s beneficial.

“But Uber can’t do that,” warns Horan, an aviation consultant who has over 40 years experience in the regulation of transportation companies—well, actually the deregulation of transportation companies. His summer job in college was working for the United States Railway Association, sharing an office with the people who would lead the successful fight to deregulate American railroads. His advisor in graduate school was Paul MacAvoy, the father of deregulation in the trucking industry.

The economics of these businesses is something he knows reasonably well.

“None of it is mysterious or rocket science,” says Horan, over the phone from his home in Phoenix.

Except for Uber.

Over the last three

“It doesn’t exist,” he says. “There is no pro-Uber argument that is anything more than smoke and mirrors.”

Anecdotally, you know he’s wrong. We’ve all waited hours for a cab to show up in the rain. We’ve all had to put up with endless busy signals on a Friday night. Uber is convenient. Press a button, pick a car, pay online.

“Yes,” says Horan. “There are more cars available at lower

It’s naive, perhaps, to think a company offering rides for money would make money from rides. But that’s not the case. The idea with almost any Silicon Valley company is that you just need a platform. Make a platform that everyone in the world will have to use and once it’s in place, great riches will spout magically.

Uber’s plan of attack has always been simple: run in and drive all the local cab companies out of business. Either set up shop illegally and ask for forgiveness

Everything the corporation has done in 10 years has been consistent with that strategy, says Horan. Uber wanted to be an unstoppable juggernaut. So far, it hasn’t worked. Last year, its ninth in operation, the company lost $4.5 billion US.

Every other major Silicon Valley firm has, over a short period of time, found a way to make a profit.

“Uber has not,” says Horan. “And no one can explain how they will.”

It’s problem of scale, he says. Taxis have existed for 100 years and there’s zero evidence of scale economies in that industry. No cab company that becomes big in Dallas suddenly expands to Houston or New Orleans. Every car on the street is the same cost as the last. But then Uber comes along with a business plan to not only become overwhelmingly dominant in one

“Uber has no advantages over the people they’re competing with,” says Horan. “The idea of capitalist competition is somebody comes in with a better product or a more efficient way of doing that and takes share away from people who are less efficient. That’s what’s supposed to happen. The opposite is happening here.”

A few years ago, Horan calculated the subsidized cost of each Uber trip to be 41

For investors hoping for an IPO next year at a $100-billion valuation, every penny counts.

Halifax is the type of market Uber is hungry for. A small metropolitan area with sprawling suburbs, a growing population, significant university presence and a burgeoning tech scene.“You're sort of arguing against hypotheticals. It’s your cousin Bernie took them last week and told you at dinner how much he liked them. Which is not serious analysis. But cousin Bernie, he's only paying half of what the ride really cost.” —Hubert Horan

tweet this

What comes with all that is a growing need for residents to move around their city, says Uber Canada public policy manager Chris Schafer.

His work focuses on deregulating bylaws across Canada to benefit ride-sharing. Already the company operates in 40 Canadian cities across the country. Halifax could be next.

Even without any local service, Uber says there were 38,000 people in HRM who opened its app so far this year. The company has been emailing those users, encouraging them to take HRM’s online taxi survey and show city hall how much demand there is for Uber in this town.

The results of the survey will come to city council sometime in the next few months, along with a $56,800 industry review of taxis and limousines from the Ottawa-based Hara Associates that will examine safety measures, driver training, licensing, best practices and “new industry technologies.”

Schafer hopes the results will “spark a conversation” at city council. Uber, he says, will be more convenient for Halifax residents, who will benefit from having the same app everyone else uses. “Tech people stepping off the plane in Halifax want to see Uber.”

Halifax can also benefit from being a late adopter, by looking at what other Canadian cities have already done and

“It’s not a case of having to invent the wheel,” says Schafer. “The wheel’s been invented.”

That makes it sound like other jurisdictions have opened their doors to ride-sharing without a hitch. But discussions about how best to regulate self-employed commercial drivers are still ongoing. Two years ago, Toronto city council tried to create a level playing field by lowering safety standards for traditional cab drivers, instead of demanding Uber adhere to the strict rules already on the books. The decision has had fatal consequences.

In a Globe and Mail editorial this week, Eric Andrew-Gee recounts how the mistakes of an ill-trained Uber driver with a nevertheless positive rating caused a car accident that killed his friend. Other cities, Andrew-Gee writes, “have rejected Uber’s logic, which says the company offers lifts from friendly amateurs, not professional drivers, and that quality control can be maintained by a driver rating system that lets riders dole out stars for performance.”

Uber has never wanted to follow the old rules that govern the taxi industry, like decent wages or driver training. The company has a long history of flouting government regulation. Its first cease-and-desist order hangs framed on the walls of its San Francisco headquarters. As Uber grew in that city 10 years ago, it carved off a unique category for how it demanded to be treated by politicians and bureaucrats. The company built a special category of regulations all its own without having to worry about things like driver training insurance or labour standards.

Horan believes there’s nothing exceptional about Uber that should let it follow a different set of rules. If you want to change the law, he says, change it for everyone.

An egalitarian market is all Uber wants, says Schafer. The current regulations in Halifax only offer an artificial advantage to local companies. In

But to facilitate that kind of innovation and let smaller companies compete competitively, local governments need to open up their regulations to the future.

“Without opening the door, you don’t get any of that innovation, small or large,” says Schafer.

Every market has rules, though. Even the one that doesn’t appear to have rules. If Halifax treats taxis and Uber as equal competitors, Horan says the set-up would still offer a “staggering artificial advantage to the companies owned by billionaires who can suffer losses until they’ve driven everyone else out of business.”

“Well, we don’t look at it that way,” counters Schafer. “Competition is healthy.”

No one’s going to argue that Halifax’s taxi industry is without problems.“You have to plan today for tomorrow. Part of that is laying the conditions for tomorrow, obviously not knowing what tomorrow's going to bring.” –Chris Schafer

tweet this

The bylaws haven’t been updated in 15 years. There are currently only 1,000 taxi licenses available and 800 extra drivers facing a potential 10-year waiting list to get on the road. There are Byzantine zoning rules and dozens of minuscule surcharges for every bridge or extra passenger. There are also safety concerns, especially coming off of a string of sexual assaults two years ago by local taxi drivers.

It’s a lot to fix. Tempting, perhaps, to cast aside all that red tape and let the market sort itself out with the help of Silicon Valley. But let’s not pretend Uber doesn’t bring with it new challenges and future risks.

Since Uber’s launch in

As for passenger safety, Uber’s record is not without blemishes. A CNN investigation found at least 103 Uber drivers in the United States accused of sexually assaulting passengers over the past four years. That number was cribbed together from police reports and civil lawsuits since Uber didn’t provide any of its own data on driver assaults. As reported by The Guardian, Uber has also defended itself in class-action lawsuits launched by assaulted passengers by arguing that Uber users agree to privately arbitrate all disputes when they sign-up for the service.

Last year, former Uber engineer Susan Fowler published a lengthy blog post accusing the company of repeatedly dismissing her complaints about sexual harassment and discrimination, protecting a repeat abuser and threatening to fire her for raising concerns. Uber ended up launching an internal investigation into the allegations that ultimately ousted co-founder and CEO Travis Kalanick.

Then, there are the working conditions.

How much the average taxi driver makes is difficult to determine. Everyone works different hours, has different cars, buys different gas at different times. Horan quotes one study that estimated the true take-home pay of the average taxi driver in three American cities was in the $10 to $13 per hour range.

“The recent studies have said Uber’s brought that down to below minimum wage,” he says.

JPMorgan Chase published a study last month that found Uber drivers are earning half what they did five years ago. The average monthly payment since 2013 for ride-share app drivers with Chase bank accounts has declined from $1,469 to $783.

Life as an Uber driver can also be nightmarish. There are stories of people sleeping in cars and pissing in bottles to not miss a fare. Frustrated with the working conditions, nearly 400,000 current and former Uber drivers in California and Massachusetts brought forward a class action lawsuit for better pay and benefits. That’s almost the entire population of HRM suing Uber.

It’s not just the Uber drivers who end up suffering, either. Taxi drivers in New York watched their annual income drop by 22

In a detailed Facebook post from earlier this year, New York taxi driver Doug Schifter wrote that he was being forced to work more than 100 hours a week to survive in the ultra-competitive free market Uber had created. The next day, Schifter went to City Hall in Lower Manhattan and killed himself with a shotgun.

“He was not driving a car to supplement the income he was getting from his crepe business and he was not trying to make a little extra money for a gym membership,” Bellafante writes. “He was not a participant in the gig economy; he was a casualty of it.”

We’re early in the conversation about all this, says Uber’s man in Canada, Chris Schafer.

The report that comes back to

There’s also the question of how accommodating Halifax should be to Uber, so recently after passing the Moving Forward Together transit upgrade and the Integrated Mobility Plan. At best, Uber can complement existing public transit through partnerships with Halifax Transit. More likely, it will put more people in cars and more cars on the road.

A report this past summer from Bruce Schaller—former deputy commissioner for traffic and planning in New York—found ride-share companies, despite claiming to be at war with personal automobile ownership, actually take users away from public transit options. Analyzing data across American cities, Schaller concludes that ride-share growth ends up adding 2.6 miles for every mile saved, “for an overall

Schafer disputes the study’s data, but it’s a problem his company seems to be aware of. Last month, Uber announced it would spend a paltry $10 million over the next three years to help cities reduce congestion. The company is also heavily lobbying for cities like New York to implement congestion pricing for drivers entering city centres.

Meanwhile, investors who have for years been pumping millions into Uber are reading about its $100-billion valuation but haven’t seen a dime. The pressure to come out with a high-priced public offering next year is driving the company’s strategy, says Horan.

To get to that valuation, Uber will need to find new ways to leverage their assets—that’s you, the customer—into other businesses. Think UberEats. Rentable scooters. Driverless cars.

Schafer isn’t familiar with Horan’s writings and wouldn’t comment on his critiques.

“My role is public policy and regulation,” he says. “I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about the business. It’s not my function.”

The game is getting governments like Halifax to play along, all without questioning the tao of Uber. The

“It is a totally-devoid-of-evidence discussion,” says Horan. “There is no argument on the other side. It is just mysterious, magical forces.”

Mysterious, magical forces that Uber has spent billions manufacturing. People believe the hype. Uber offers a perception of the future and we want to be seen as friendly to its cause.

“Don’t bother me with details,” Honan says, mockingly. “This is innovation.”