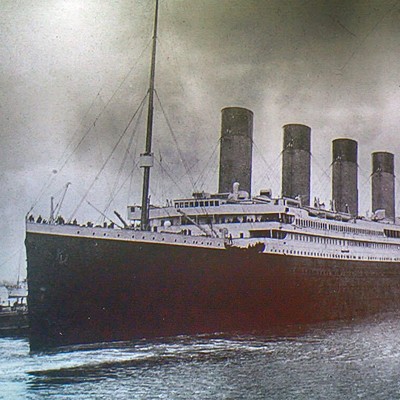

New Year’s Day brought the world a fresh look at the sinking of the Titanic, and it has nothing to do with the claim the boat that sank off Newfoundland was actually Titanic’s sister ship, the Olympic. In Titanic: The New Evidence, a documentary aired January 1 on England’s Channel 4, modern animation techniques are used to glean evidence from a set of recently discovered 1912 photographs. Senan Molony, the longtime Titanic investigator at the heart of the documentary, calls the photos “the Titanic equivalent of King Tutankhamun’s tomb.”

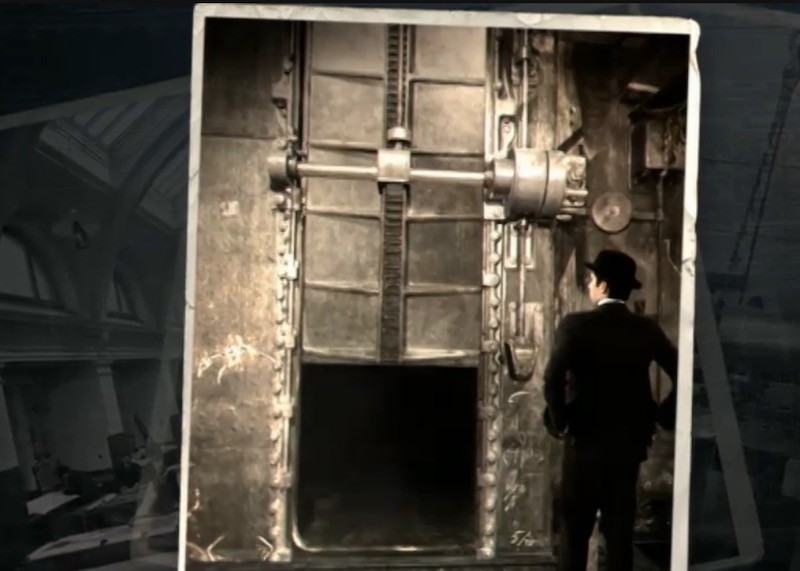

What Molony sees in the images, and what the doc sells via animations, is proof of a catastrophic fire in one of the ship’s coal storage bunkers. Apparently such a fire was normal enough for coal-powered vessels, and the stokers would deal by digging the burning fuel out of the bunker. This was such a common fact of life at sea that when the fire came up at the Titanic inquiry in London, the presiding Lord Mersey is said to have dismissed any suggestion it played a role in the epic tragedy. But maybe the biggest-ever size of Titanic’s bunkers made for a larger and harder-to-control burn that compromised the hull, no matter what Lord Mersey thought.

Starting with the tell-tale discolouration on the ship’s side in the photos, Molony combines it with a 1912 newspaper quote from crewmember John Dilley—“From the day we sailed, the Titanic was on fire”—to stoke his theory. To fan the flames, he cites a miners’ strike that made coal so rare the Titanic could only take on the bare minimum fuel to make it across the Atlantic. Because fuel was scarce on board, and because slowing down then speeding up burns more fuel than going at a single speed, this explains why captain Edward Smith kept going so fast despite iceberg warnings. To Molony this is clearly a gamble between running out of fuel before New York and an “unsinkable” ship running into icebergian disaster. “Against the higher risk of embarrassment, they chose to go with the lower risk of catastrophe,” he says Molony. And of course they lost.

As The New Evidence explains, immediately after the iceberg collision the Titanic’s designer went to assess the damage. Considering the hull breach and those legendary water-tight bulkheads, the designer thought the ship was safe—as long as a critical bulkhead didn’t let go. Unfortunately, it happened to be the very bulkhead that an uncontrolled coal fire might have burned behind for nearly two weeks, from the Titanic’s April 2, 1912 launch through the night of April 14, weakening the metal to devastating effect.

There’s little question that the bulkhead breached. In New York's Titanic inquiry, lead firefighter Fred Barrett testified that he witnessed it: “I saw a wave of green foam come tearing through between the boilers.” What’s new is the idea that a fire enabled the breach, that the Titanic could have stayed afloat if not for that fire. And of course the documentary renews mistrust of the executives who knew about the fire, but who would rather risk 3,500 lives than face the embarrassment of Titanic running out of gas at sea.

Is Molony right? The crux of his argument is not about the existence of a fire, but about its effect. Where Lord Mersey thinks coal fires happen too commonly to matter, Molony says in that giant ship a common fire became uncommon: So large and unprecedented that proof of it appears as a darkened area on the hull in some photos that turned up from 1912. The dark spot is the new evidence in The New Evidence, and the "fact" it isn't just glare from the water is "confirmed" through digital animation. It’s thin gruel, inconsequential to most people living or dead, including the 150 Titanic victims buried in Halifax. At least the documentary is inoffensive as Titanic memorabilia goes, serving its role primarily as new evidence that some fascinations are unsinkable.