OTTAWA - 1977-1990

I come from a Zionist household. I learn from an early age that anti-Semitism is always on the rise, that another Holocaust is always just around the corner and that no matter what, Israel is always right. That's a lot for a kid to handle.

Twice a week, after regular school, I head to Hebrew school. I meet kids from all over Ottawa, and we learn how to be Jewish. We study Hebrew. We raise money to plant trees in Canada Park. We get certificates in the mail from Israel, thanking us for our trees, and tiny minds fill with glee at the thought of saplings growing in a park. Nobody ever tells us that Canada Park is built on the site of demolished Palestinian villages.

We learn to consider Israel as our homeland, a fallback zone against ever-present anti-Semitic hordes. We learn that we Jews, whoever we were, had lived in Israel for thousands of years, and that we must defend her. We learn of Israel's military might, but never of the untold billions in American money and weapons gifted to her over the years. We learn of Palestinian suicide bombers, but never of illegal settlements and occupied territories. We learn to accept whatever Israel does as right, and whatever Palestinians does as wrong. It is that simple.

ISRAEL - 1998-99

Fifteen years later, as a disillusioned youth, I think myself a candidate for the Israeli army. I move to Israel to live on a kibbutz. I figure the streets will be filled with happy Jews, welcoming me to my spiritual home. Instead, after getting kicked off said kibbutz, I find myself down-and-out in Tel Aviv, sleeping eight to a room and line-cooking. My cookmate is a Palestinian named Azi. He isn't allowed to leave the kitchen, because patrons won't eat there if they know a Palestinian is their cook. When he gets evicted, we have a hard time finding him somewhere to stay, as many hostels in Tel Aviv are No Arabs Allowed.

In the years following, more than once I turn my back on Judaism. But I always come back. It's part of my heritage---lots of my ancestors did get killed in the Holocaust, and the flight from religious persecution, three generations ago, is the reason I'm here, born, and now living in Halifax. I can't forget that it's part of who I am. I'm a Jew. But I'm no Zionist.

HALIFAX - May/June, 2011

I start writing for the Media Co-op. I interview key figures in the Palestine solidarity movement, and am offered a spot on the Canadian Boat to Gaza. We are to join 10 other boats, and over 1,000 activists from around the world, in the Freedom Flotilla II. We will attempt to sail from Greece to Gaza, challenging Israel's sea blockade of the embattled Palestinian territory. Last year, the first Freedom Flotilla ended in bloodshed and disaster, as the Israeli Defense Forces boarded the Turkish ship, the MV Mavi Marmara, on the high seas, and killed nine activists. How could I say no?

I also learn that the province of Nova Scotia will stage a government-sanctioned trade initiative to Israel in October. Premier Darrell Dexter returns from a trip to Israel, gushing fascination with the country and its people. He says nothing about Palestine. He says nothing about the blockade of Gaza. It's as though it doesn't exist. And I'm right back in Hebrew school all over again.

Except now it's 25 years later. I start an import/export company and create my own trade mission from Nova Scotia to Gaza. The Israeli blockade of Gaza involves a crippling of trade, the logic of which completely escapes me. I call my company Peaceful Waters Trading Company.

I go to local businesses, explain myself and receive offers of support that could fill a boat. Small businesspeople load me with samples of salt cod, honey, seeds, soaps, preserves and pottery. I head to Greece, where the majority of the Flotilla is congregated.

ATHENS - June 19, 2011

In years past, the Greek islands have been safe harbour for boats sailing for Gaza. But Greece now teeters on the brink of bankruptcy. The financial giant Goldman Sachs was very involved in propping up the Greek economy, and their scheme has fallen apart. Debts hidden in bond sales and currency exchanges have been revealed. Greece's credit rating has been downgraded. The Greek economy is beholden to the International Monetary Fund.

The IMF demands cuts to social services and large-scale privatization of formerly public services. If Greece doesn't accept the austerity measures attached to IMF's multi-billion-dollar loan, prime minister George Papandreou warns the government will run out of money to pay the public service.

But if Greece votes to accept more IMF money, the Greek public---which has taken control of town squares across the country--- may seize parliament. In Athens, the people have sequestered Syndagma Square, which faces the parliament buildings. The people have organized a tent city, a food detail and a media centre, along with all the little things that make for a good square seizure. Thousands, from grandmothers to children, gather nightly in Syndagma to jeer Papandreou and demand his party's resignation.

"We have a situation where the population is profoundly disenfranchised to the demands of the government to tighten belts," says Michael Chronopolous, a former anarchist filmmaker and volunteer Syndagma masseuse, "where no more tightening can be done. From taxi drivers to teachers to the unemployed, there doesn't seem to be any hope. I Mavri Trypa, The Black Hole, is an image that keeps coming up in conversation time and time again. The ordinary Greek person, to tell you the truth, doesn't really see any hope in all of this."

The situation is as sticky as fresh baklava. The political climate is roiling under the feet of the Freedom Flotilla II, and there's not a thing to be done. The Greek government is weak. In an attempt to placate the people, Papandreou shuffled his cabinet. The foreign minister, who appeared to be a friend to the Flotilla movement, quit his post in disgust. This isn't a good sign.

This government is wide-open to political pressure from Israel and its international friends: from Ban Ki-Moon to Hillary Clinton to John Baird to almost every EU foreign minister in between, these friends are warning participants not to join the Flotilla. Israel doesn't want the boats to sail at all, and most of the Western world is putting the screws to the Greeks to make it so.

As for the Greek people, they're embroiled in a revolution with key points much closer to home. Freedom for Gaza is far from the collective mind at the moment, and it will be tough to count on a public uprising of support for the Flotilla in Greece. I Mavri Trypa---The Black Hole, indeed.

AGIOS NICHOLAOS, CRETE - June 23, 2011

As we approach our theoretical date of sailing, Flotilla participants scatter across the Greek archipelago. The plan is to reconvene in international waters, and from there make our push. Participants with the Canadian Boat to Gaza, which include Australians, Belgians and Danes, head to the island of Crete.

There are 50 of us, meeting for the first time, holed up in a pair of swanky hotels. We overlook palm trees, rust-coloured hills and the gentle turquoise Mediterranean. This is the hedonistic world of breakfast buffets, beach umbrellas and island-hopping tours. Nice digs, but there's a false sense of security here. Last year, several boats were sabotaged. Over half the group are senior citizens. Will this force challenge the Israel Defense Forces on the high seas? Not without medication.

But there's more to grandma than meets the eye. Grandma with the cane is Mary Hughes-Thompson. She's 77, broke the Gaza blockade by boat in 2008 and was beaten half to death by Israeli settlers in an olive grove. That quiet guy in the corner with the wire-rim glasses and the bucket hat? Harmeet Sooden, kidnapped in Iraq in 2005, volunteering as a Christian peacekeeper. His captors kept him chained for four months. And the old man with the sunburnt head, the wax-able moustache and a penchant for wearing Speedos, even when not swimming? That's former war correspondent, and Belgian senator, Josy Dubie. He bargained for his life in Iran. This may be a ragtag group, but more than canapes and cocktails beat beneath their breasts.

We spend four days learning how to be a peaceful activist on a boat courting a collision course with the IDF. We learn to take a beating, how to be stepped on and how to suck an onion to mitigate tear gas. We discuss jail solidarity plans and how the IDF will probably film us eating the food they'll theoretically offer us, then use the footage as propaganda on how humane the IDF can be. We decide not to bite the apple if it's offered.

From across the Med, in Tel Aviv, the Israeli spin-machine beats its war drum; we feel the reverberations. They'll meet us with force, they say. They're testing new water cannons, they threaten. It's one thing to read this. It's another to read this and realize it's it's going to happen to you.

Training also carries moments of poignancy. We discuss who would like to be where if the IDF arrives. Most vote to block the path to the wheel cabin, sitting with our arms linked. Such an action is personally foolish, and seems to invite violence against us. But collectively, it appears that we consider it a necessary "final" step. An understanding of willingness and common cause passes through the group.

But while we train, the net cast around the Flotilla project is drawn tight. In rapid succession, the American boat---The Audacity of Hope---is slapped with a lawsuit questioning her seaworthiness. The Greek-Swedish-Norwegian boat is sabotaged. The Irish boat is also sabotaged, the act discovered at sea. Israel does not deny responsibility. There are lip-readers in the local cafe. We are being followed. Zionist sympathizers threaten to burn down my house in Halifax. And my mom wonders if I am a terrorist.

ABOARD THE TAHRIR - July 1, 2011

The lynchpin to the mission breaks. Greek parliament bows to international pressure, and Papandreou issues an edict declaring that no boats may sail from Greece to Gaza. In the coming weeks Greece and Israel participate in joint military ventures, and Greek officials are publicly thanked by their Israeli counterparts.

As for our boat, the Tahrir, representatives from the port authority promptly arrive. They demand her travel log. Sandra Ruch, the Tahrir's owner, refuses to part with the log, believing that once the document leaves her sight it will be gone. An emergency call goes out, and we congregate onboard. Moments ago the Tahrir was an incognito ferry. Now we unfurl her banners. Now, 50 strong, we chant "Shame on Papandreou!" Now we fly the Palestinian flag. We march through the streets to the port-authority offices. An officer at the port authority cannot answer why they are doing what they are doing. Only that they are following orders.

Things get worse. The Tahrir's captain and crew inform us they will not sail. They have too much to lose. If caught, the Greek captain will be arrested, serve time and have his livelihood taken away. Our captain, George, is a lion of a man---he's already attempted to sail to Gaza five times. But lions get tamed.

These are desperate times. No legal way to leave. No captain and crew. There are also return tickets to consider, and now that we have moved out of the hotel and onto the hard floor of the boat, the clock is ticking on the whole mission.

HIGH SEAS - July 4, 2011

Almost $500,000 has been raised for this effort. Fifty people have collectively travelled tens of thousands of kilometres to be here. The money expended on the Flotilla climbs into the millions of dollars. And it's been a full year's worth of work for the organizers.

The eye of the mainstream media is upon us. But mainstream media has a short attention span, and if our boat doesn't sail within the next 24 hours, this story dies. If there's going to be a climax, it must happen soon. The steering committee decides that we will sail illegally, regardless of the edict. We will attempt to outrun the Greek coast guard.

The next morning we arrange for a diversion at the marina. A Greek coast guard cutter is berthed right next to us, and we need to get the jump on her. We pretend to be having a party. They're not buying it. Truth be told, it's a feeble attempt. But secreted behind the Tahrir are two of the activists in rented kayaks. That's the trump card.

The Tahrir starts her engines. The cutter starts hers. And as the engines rumble, Michael Coleman from Australia and Soha Kneen from Ottawa paddle forward and position themselves in front of the cutter's nose. Coleman grabs the anchor and holds on while the irate Greeks try to bounce a buoy off of Kneen's head. The Tahrir executes a three-point turn in the marina, and we are away. Aboard we cheer voraciously and sail for Gaza.

In seconds, however, a coast-guard Zodiac motors up along our port side. There are two police-types on board, and one guy in camo fatigues with an M16. They're not happy. They'd like us to stop now. We don't.

The cutter then comes racing up on our starboard. She edges ahead and tries to cut us off. The Tahrir, an antiquated ferry, is not meant for action like this. But she rumbles on at full throttle, ramming through the coast-guard's wake.

A second Zodiac pulls up off the starboard bow. There are now three boats in the chase. An angry, mustachioed man is in command of this second Zodiac. They edge closer.

A railing is grasped, a leg is extended from the Zodiac to the Tahrir, and the Greeks are aboard. In a flash they seize an empty wheelhouse. Our makeshift crew has scattered. The Tahrir is on autopilot. They find no captain.

It is surreal, as they seize our boat and tow us back to port, to listen to the incredulity of our apologetic captors. The Greeks--- with guns, mind you---whisper regrets, and in hushed tones tell us they hate Israel for making them do this. Later, we all convene around a laptop and look at the photos I snapped of them as they attacked us. They laugh and point each other out on the screen. This is the outsourced "soft hand" of Israeli foreign policy. They are the enemy, but as we share gyros, it's hard to hate them.

We are towed back to Agios Nicholaos, left at the port-authority marina for a night and a day. The coast guard has no captain to lay charges upon, and none of us will comment. We assume, correctly, that the Greeks won't process charges against 50 captains--- if we just stay quiet, we'll all go free.

But they want to save face and pin this mess on somebody, so they charge Coleman and Kneen, the "kayaktivists," with obstructing a coast guard vessel, and Sandra Ruch, the owner, with owning a boat that sailed illegally. But the story has gone international, and the whole legality of Papandreou's edict, in an international-justice sense, rests on questionable ground. Can a country ban a boat from sailing to another country, just because a third country asks them to? Coleman, Kneen and Ruch get off with 30-day suspended sentences and fines.

The Freedom Flotilla II has been reduced to one boat, sailing onwards from Corsica. As for us, we are told to consider it a success. If we are not at our end goal, then at least we are a stone in the path. Inside I worry that we shifted the focus away from Palestine, and onto a bunch of boats that didn't sail.

EGYPT - July 9-14, 2011

The Tahrir has been mothballed for now, but I can't go home. There's a deep sadness, and the Nova Scotia-to-Gaza trade mission to consider. I'll try and get to Gaza by way of Rafah, which smacks of asking the warden if I might visit the prisoners. It also runs counter to the Flotilla's original goal of declaring the blockade illegal. I agree in principle, but I'm not part of the Flotilla anymore. Now I'm just a guy with salt cod from Shearwater in his backpack.

In Cairo, I visit Tahrir Square, where the spirit of the revolution is alive and well. I explain where I have been, and that I don't know when the Freedom Boats are coming to Gaza this year.

I catch an overnight bus to Taba, and bribe a man named Ismail to drive me across the Sinai desert to Rafah in the back of a mini-van. Rafah is now only sporadically open to Palestinian and Egyptian foot traffic, and, at the time of writing, not at all to men between the ages of 18 and 40. I hope my press pass, and a letter from the editor of The Coast will strike the right chord with the border police.

Rafah, for what it is, serves the border- crossing. It's really just a few tin shacks, a coffee shop and sand, as far as the eye can see. But just beyond the fence, just beyond the massive compound and looming black-iron gates, from which shouting people lugging suitcases are today pouring, is Gaza. Ismail bids me goodbye at the first checkpoint of teenage Egyptian soldiers with machine guns.

They let me pass with a sweeping gesture of their guns. I figure things are going to go smoothly. But at the gate, the white-clad guards are not having it. I hand them my press pass. "No." I try to give them a bribe. There's nothing doing.

After half an hour of pleading, a guard tells me "to go sit over there," meaning the coffee shop at the end of the road. Dejected, I dust sand off a plastic chair and plunk down.

I take out the Nova Scotia honey, the preserves, and the soaps from my pack. I offer honey to the family sitting beside me, but they've never seen honey in a plastic bear, and there's a certain off-putting lunacy to my actions now. Who is this blue-eyed white man trying to give away honey bears? I pantomime scrubbing myself in the shower while humming a tune, and manage to at least give away a bar of soap.

A group of travellers in desert khakis sits down at the adjoining table. Patches emblazoned on their backs say Music for Peace. They are Italians, who have been waiting for four days, with their flatbeds of medical supplies, for permission to cross. I tell them about the Flotilla, and my now-defunct trade mission. They suggest I go back to Cairo, and try for a waiver from the Egyptian Foreign Ministry office, and then try again. But that's not for me now. I beg the Music for Peace people to take me with them, but it is impossible.

There is a motion from the fence, and the Music for Peace flatbeds rumble to life. The khaki-clad foursome extinguish their cigarettes, and move towards the trucks. In desperation I try to force honey and cherry- tomato salsa on them, but they tell me it is very difficult, and refuse. "Please," I say. "Just take this."

I grab a small glazed tile, which fits in the palm of my hand, given to me by Scott Barber of Coracle Pottery. On the back of the tile it says "To Gaza With Love. Scott Barber, Nova Scotia, Canada."

One of the Music for Peace-niks, Valentina, pockets the tile. And then they are gone to Gaza. And I am alone in Rafah at the coffee shop at the end of the road.

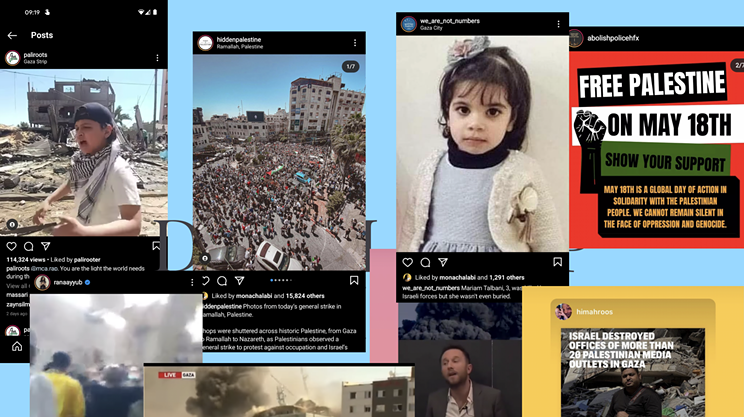

Miles Howe is a writer and social activist from Ottawa, now living in Halifax. Photos from Howe's trip will be hanging at the Good Food Emporium, 2186 Windsor Street. The exhibit opens Friday, August 19 at 8pm with guest speakers.