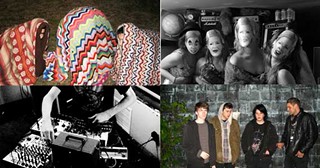

"Obviously there's always weirdos in every city doing experimental music," musician and composer Zachary Fairbrother explains, nonchalantly. Those weirdos come out to expose the seedy underbelly of Halifax's music scene---experimental noise, and other offbeat bands and performers---this weekend at the fourth Obey Convention. What started as a handful of shows at One World Cafe in 2007 has grown into a festival that's recognized by underground music fans across the country and attracted headliners from Canada, the US and as far away as Paris and Beijing. So what is going on in Halifax that's making it a mecca for weird music?

From Obey to basement house shows to bar shows to an event in the University of King's College Pit theatre last summer combining experimental bands, performance art and free French fries, plenty of local musicians are doing strange things right now. Experimental music in Halifax is nothing new, but in the past few years the scene feels particularly active among younger musicians, with labels and collectives like Divorce Records (which presents Obey), Snapped In Half and the Radiator Collective releasing tons of albums and compilations and putting on shows.

Dalhousie University had an experimental music lab in the 1970s and '80s (still existing as its electroacoustic studio), and NSCAD, during its conceptual-art heyday in the '60s and '70s, brought in performers like Charlemagne Palestine. Local experimental music collective Upstream celebrated its 20th birthday earlier this month with a concert series and exhibition at Saint Mary's University Art Gallery. With an excess of creative young minds---and the older ones who've stuck around to nurture them---as well as our relative geographic isolation and months of dreary weather, Halifax has often served as a breeding ground for experimentation.

"Halifax bewilders me to no end," writes Aaron Levin, an Edmonton-based radio programmer and the founder of the blog Weird Canada, dedicated to reviews of Canadian "fringe music." Levin has sung the praises of Nova Scotian artists like York Redoubt, Pig, Gown, Mess Folk and more; he's making his first trip here for the festival.

According to Levin, a city as small and isolated as Halifax shouldn't have any music scene, "yet it has one of the largest and most diverse music scenes in Canada. It shouldn't exist. But it does and that amazes me all the time." Inspired by Obey, Levin founded Wyrd Fest, an Edmonton event dedicated to similar types of music. "Simply knowing that festivals with that kind of niche focus not only happen, but are seemingly sustainable, was enough to encourage me to try."

Over the past few years, out of Montreal and elsewhere, "weird punk" has grown to prominence---an umbrella term for an amalgam of bands ranging from noise to garage rock to punk-inspired electronica. "You have all these bands that don't necessarily sound alike---but that is what they sound like: weird punk bands," summarizes Darcy Spidle, manager of Divorce Records and Obey Convention founder.

"We saw this real direct line between punk music being this challenge to the norm, the mainstream, and experimental music being the same thing. People called [punk] noise when they first heard it because it didn't make sense to them...I think that original spirit is the same spirit that we are trying to pin on experimental music---and I really think that experimental music is the wrong term for it, but I haven't come up with anything better...it conjures up an idea of real academic, geeky stuff," he says.

Spidle traces his involvement with the scene back to the Agricola venue Salvation (the space that was later One World) around 2003-2004, where his friend Cory Lavender ran an experimental poetry and music night called Tensity every Sunday. "We just would do different experiments...tape recorder bands, improvised guitar to found cassettes, things like that...we fooled around. It wasn't overly popular," he laughs.

Popular or not, the evenings provided Spidle the impetus to form a now-defunct noise band, Shit Cook, and put together a compilation, Die Like An Animal Dies, on Divorce Records, that tried to capture the scene at the time. He cites the compilation as the start of the label in its present state. They launched the compilation at One World in the spring of 2006, which Spidle half-seriously refers to as the first Obey Convention; in 2007 a small-scale festival was improvised around one touring band's visit. In 2008 it expanded to involve more venues and bring in a larger art component, through exhibitions and a zine-and-record fair; it's become a bit bigger and more well-known with every following year.

Spidle sees a tenuous relationship between the music he presents and punk, originally aiming to group the two in Obey. The two communities can appear quite disparate: "The idea that punk can be something other than punk---that's kind of a controversial concept. It's about not having to know formulas and be a part of some canon: that's what we're really trying to do."

Zachary Fairbrother studied composition at Dalhousie and has been involved with experimental music from its more formal, academic side to playing in psychedelic band Omon Ra. Fairbrother is presenting Buddha Box 2.0 at Obey, the second edition of his composition thesis project. Buddha Box 1.0 was performed by musician Tim Crofts on prepared piano---a piano altered through placing objects on and between its strings, a technique pioneered by John Cage---using bows, prayer bowls and something called a Buddha Machine, a toy with "looping chants to assist with meditation."

Fairbrother played in a 200-person guitar orchestra in New York last year for composer Rhys Chatham and originally conceived of version 2.0 as one, but has condensed it to a five-person group. "It doesn't require any specific guitar knowledge. The instruments basically play themselves, it's kind of ambient and drone-y," he says.

"I like Obey because it gets more young people involved," explains Fairbrother, who has also played with other projects spearheaded by older local musicians like the Upstream collective.

Ideally, Obey tries to group like-minded folks and those who don't yet know that they're like-minded, by using a sort of curatorial premise in booking shows, with performers from different ends of the underground spectrum, or bigger, more accessible artists with people doing lesser-known, weirder stuff.

"It's about challenging music---you kind of trick people into coming out," says Spidle.