Today I'm at at Utility and Review Board hearing, following an appeal Olympic International Realty Ltd. has filed against a 2006 Northwest Community Council decision related to phased development in the Paper Mill Lake.

It doesn't get much more obscure than this, and the story gets quite convoluted. I won't now get into this in great detail, but I do want to mention the broad outline of the case, because I think it illustrates something important.

This story starts with a fellow named Ali Ahmadi, who was for a while in partnership with developer Navid Saberi. Another Ali, Ali Roshani, testified today that Ahmadi named the company "United Gulf Developments," after Ahmadi's home country of Kuwait, the reference being to the Persian Gulf. "He had a billion dollars," Roshani said of Ahmadi.

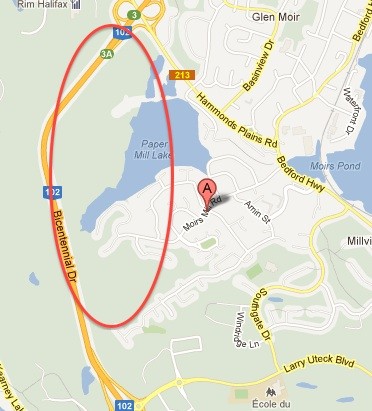

United Gulf bought a big parcel of land east of the Bicentennial Highway, west of Paper Mill Lake, south of Hammond Plains Road and, roughly, north of Oceanview Drive. I've noted the area generally, on a Google maps:

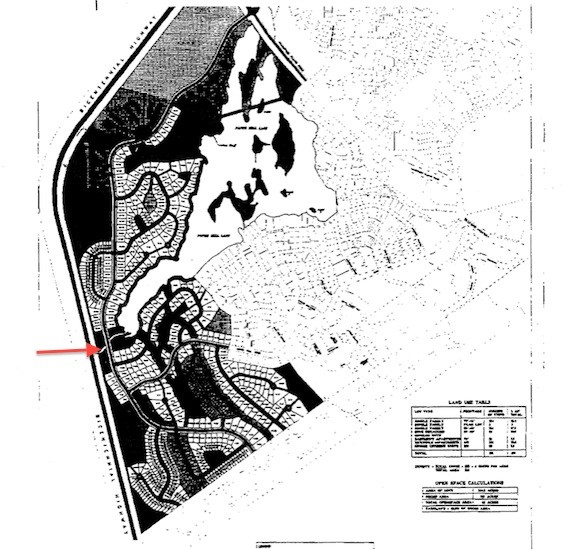

Way back in 1995, the previous owner of the property proposed development of the area, as shown in this map:

The red arrow points to Kearney Run, a small stream that runs from the west of the highway to the lake, and which bisects the property.

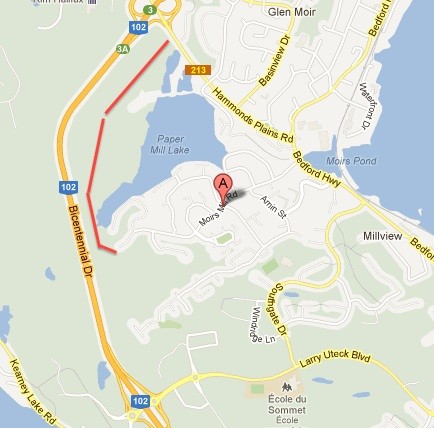

Note that until recently, Larry Uteck Boulevard, and its intersection with the highway did not exist. In 1995, the former town of Bedford was worried that development of this property would result in lots more traffic being dumped on the Bedford Highway, and so adopted a planning rule: the property could not be developed until a collector road was built from Moirs Mill Road to Hammonds Plain Road, something like this (in red):

United Gulf bought the property with the requirement for the connector road in place. (In reality, the property transactions are much more complex than I'm making them here, but this shorthand is accurate enough for our purposes.)

After United Gulf acquired the property, however, Ali Ahmadi and Navid Saberi had a falling out, and ended their partnership. Saberi kept the "United Gulf" name, and a reconstituted company that didn't involve Ahmadi. The land was divided—Saberi took ownership of the north part of the property, north of Kearny Run, and Ahmadi had title to the south part of the property, about 75 acres south of Kearney Run.

With Ahmadi out of the picture, Saberi's United Gulf has gone on to become one of the largest development companies in Halifax. Through a related company, Greater Homes, Saberi has built several subdivisions, and United Gulf itself builds highrises, several in the Clayton Park area, and is the company behind the Skye Halifax proposal for two 48-storey buildings downtown.

But back behind Paper Mill Lake, with the requirement for the connector road still in place, Ahmadi wasn't able to develop his part of the property, south of Kearney Run, unless Saberi also built the portion of the connector road that went through his property, north of Kearney Run. And Saberi wasn't building the road, and still hasn't built it. Ali Roshani testified today that Saberi has refused to build the road because of bad blood with Ahmadi, depriving Ahmadi of any potential to profit from development of the company. Ahmadi was disgusted with the situation, and moved back to Kuwait. "He doesn't like Canada," Roshani testified.

This is where Ali Roshani enters the story. Roshani was born in Iran and immigrated to Canada in 1980; he learned English, went to TUNS and ended up running Olympic, a small real estate brokerage company housed in an office above the Bluenose diner downtown.

Learning of the undeveloped Paper Mill Lake property, in 2004 Roshani called Ahmadi in Kuwait, and asked to represent him. The two came to an agreement that allowed Roshani to try to develop the property.

Roshani testified that he tried several times to get Saberi to agree to build the connector road, going so far as to offer to pay for the whole road, including the northern section, with Saberi only paying him back, without interest, as Saberi developed his land. Still, testified Roshani, Saberi wasn't going to cooperate.

At that point, Roshani hired several consultants, including Dan O'Halloran, to find a way around the planning requirement for a connector road all the way north to Hammond Plains Road.

The consultants did exactly that, and O'Halloran's traffic analysis is part of the court record. It argues that since 1995, the situation on the ground has changed. There are new roads that didn't exist, like Oceanview Drive to Nelson Landing Road, that provide a second exit to Bedford Highway from Ahmadi's property, in addition to Moirs Mill Road. Moreover, said O'Halloran, the addition of Larry Uteck Road presented a wonderful opportunity for taking traffic off the Bedford Highway entirely and, he argued, we wouldn't want traffic going out to Hammond Plains Road in any event.

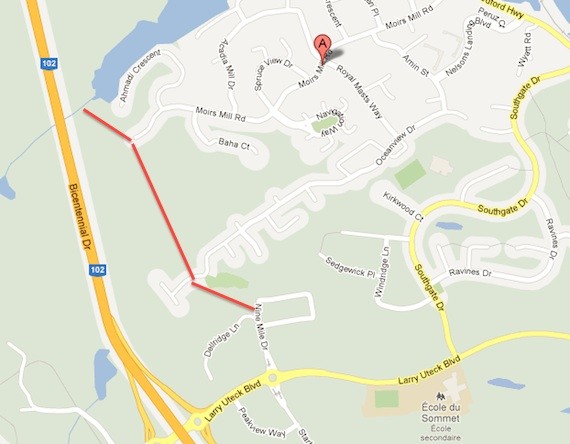

WIth the traffic study in hand, Roshani brought a new proposal to the city: He'd build the southern portion of the connector road, from Moirs Mill Road to Kearney Run. But, additionally, he would extend the connector road to the south, across Oceanview Drive to the new Nine Mile Road, and so ultimately connecting to Larry Uteck Boulevard. Roshani's new proposal would look like this (with the road in red):

This revised connector road would need the cooperation of another property owner—the Armoyan Group, which owns some of the property around Nine Mile Road. But it doesn't matter: the city rejected that proposal, and maintains to this day that the originally contemplated connector road—from Moirs Mill Lake, north across Kearney Run and all the way up to Hammonds Plains Road—before Roshani can develop any of the Ahmadi property.

The ins and outs of Roshani's appeals, lawsuits and other claims would take forever to explain. The Court of Appeal record alone is collected in 12 two-inch thick volumes. Roshani has been frustrated at every turn; he has gone through five or six lawyers, he claims a conspiracy on the part of former city councillor Len Goucher against him (a claim that a court rejected) and by mayor Peter Kelly (a claim that the UARB has ruled out of order). Roshani paid for Ahmadi to fly here from Kuwait to testify, and for a translator because Ahmadi does not speak English. Some of the story is fantastic: one of his lawyers' house burned down, with his court papers, the day before a hearing. Frustrated at the Court of of Appeals, with another flurry of paperwork, available on the UARB website (type "Olympic" in matter title box).

And, to be honest, Roshani is a difficult person to get a coherent story from. He is so deeply connected to his case that he can't easily speak in a plain narrative; he veers off in asides, then asides from asides, then corners around to a tangent, then a tangent of a tangent. It is, frankly, exhausting listening to Roshani. He has the passion of someone who sees himself as wronged at every front, and if only he was heard out, anyone could see it. But by the time you've heard him out, there are so many disconnected details, you've lost track of the trail.

Moreover, Roshani isn't rich. Some readers will probably recognize him as the driver of a red cab that services the airport. And he isn't slick in the way of developers who can slice their way though the bureaucracy with a simple phone call.

But here's the thing. I've been following Roshani's case from afar for over a year, and have read through the court record every now and then, and while it's a complex story coming from a confusing story teller, when I sit down and think about it, there seems to be something there. It is, actually, an interesting story.

That's not to say that I'm convinced that Roshani is absolutely in the right here, and should be able to develop the property with the re-aligned connector road. Maybe, maybe not. I don't know how the judge will rule.

But let's re-frame the question. Let's imagine that it was the Armoyans, or Saberi, or Clayton Development, that came before the city with a revised traffic study that they said superseded an 18-year-old planning requirement. What do you think would happen? Would the city reject it? Or would the bureaucracy move in ways that have eluded Roshani?

Like I said, Roshani's case is immensely complex, and has aspects that I haven't discussed above. One of those aspects concerns density of the possible development, which is not directly relevant to Roshani's appeal, but there was a telling exchange between the city's lawyer, Randolph Kinghorn, and Roshani. Kinghorn was arguing that under existing zoning, Roshani was allowed to build just one unit per acre, but with his development proposal Roshani was seeking an amendment to planning rules that would allow him four and a half units per acre, which, Kinghorn argued, was too dense. Here's Roshani's reply:

Ours was four and a half [units per acre]. Now I'll tell you why I said that. Larry Uteck Boulevard—that subdivision—look at how many units per acre you have given it, density. In a meeting Mr. Goucher and Mr. Bleu, the offer that came up, they offered me to take the $3 million to sell this land to Clayton [Developments] and Cresco, go away, and they'll give more density to [Clayton and Cresco] to cover up their $3 million cost. I said, "I'm not going to do that." So, people have a right, you will agree—if not me, somebody else is going to buy this. Do you honestly think that somebody else is going to walk into that land and say, "i'm just going to do four and a half units"? I guarentee you that the next developer is going to sit there, the least they will think about is six units [per acre]. The most? Sky's the limit. They'll ask for multi units, do this, do that. And what is it, an amendment [to planning rules]? Yes, an amendment. Some strong guy, you won't be fighting him.I don't mean to get into a debate over density here, but Roshani's point is dead-on: The Armoryans and Claytons and United Gulfs of the world have no trouble getting planning rules amended, getting street requirements tweaked with new traffic studies.[...]

That is basically what was on my mind. Let me do it, because I'm only doing four and a half units, not 20 units per acre. I'm only doing four and a half! The next development [to his property] was Larry Uteck Boulevard, Mr. Armoyan's subdivision, look at the density they got. Look at the other developers, what they get, you know, they get more, per acre. On top of Main Avenue, 22 or something, per acre they get. Mine has only four and a half.

The cab drivers of the world, not so much.

There's a lot more to this case. Everyone I've spoken to privately who knows the details of Roshani's travails, tells me that he's been wronged. Over time, I intend to drill down more into the details of it, because the court record is a gold mine of details of the internal workings of the local political scene. Stay tuned.

I still don't know if there was an active conspiracy against Roshani, but there seems little doubt that there was a passive one, that the lay of the political landscape conspired against him. If he was powerful, and connected, he wouldn't be in the situation he's in now.